If you feel a need to search for moral cowardice then, in my experience, literary festivals are likely to be as happy a hunting ground as any.

Should you be lucky enough to find Peter Carey, Michael Ondaatje, Francine Prose, Teju Cole, Rachel Kushner or Taiye Selasi listed in the programme then, by jove, your ship will have come in. Moral dwarves, each of them.

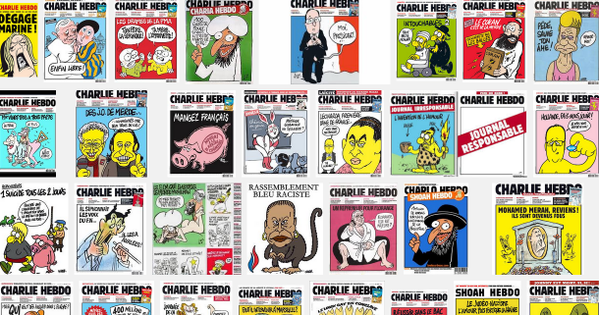

You see they are, all of them, unhappy that PEN America decided that, this year of all years, it would honour the editors and staff of Charlie Hebdo with PEN’s annual Freedom of Expression Courage award at the organisation’s annual gala. So unhappy, in fact, that they have decided to ‘boycott’ the evening.

According to Ms Kushner, Charlie Hebdo promoted a kind of ‘cultural intolerance’ and insisted upon ‘a kind of forced secular view’. Mr Carey, for his ninnyish part, deplores the ‘hideous crime’ but, naturally, is more concerned about whether it ‘was a freedom-of-speech for PEN America to be so self-righteous about’. Moreover, ‘All this is complicated by PEN’s seeming blindness to the cultural arrogance of the French nation, which does not recognise its moral obligation to a large and disempowered segment of their population.’

Mohammed wept.

These imbeciles should be asked a few stern questions. Among them: why does Charlie Hebdo’s editorial stance have anything to do with anything? Why should the magazine’s staff be reckoned responsible for the supposed failings of the French state? What, indeed, is arrogant – culturally or not – about insisting that some lines should not be crossed and that machine-gunning journalists because you disapprove of their ideas is, however controversially, one of those lines?

Apparently, however, it’s only a real crime when the wrong kind of people are murdered. The suckers and bigots at Charlie Hebdo should have known better and, my word, it’s actually and truly offensive that their deaths be honoured in this fashion. Root causes, don’t you know?

I wonder if these people also think the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses also had it coming? I wonder if they think there would be something unseemly about awarding Salman Rushdie – and all those involved in publishing his novel – awards for their courageous defence of liberty? People died and many others risked assassination to bring The Satanic Verses into print. Perhaps, however, there is a feeling that this was a noble enterprise because it was somehow a more literary enterprise? (Except, of course, plenty of people failed the Rushdie test too.)

And I wonder if these novelists would be appalled if they or their translators were targeted and perhaps killed for the ‘crime’ of offending someone, somewhere? Would they deplore any awards made in their memory? Somehow, I doubt it.

Ah, but Charlie Hebdo is different. Except, no, actually, it’s not.

Only intelligent people can complicate such a simple business and get everything so completely wrong. Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons and editorial stance are entirely beside the point. Insisting that the problem somehow began with Charlie Hebdo means, unavoidably, blaming the victims for their slaughter. It is a truly repugnant position.

You need not like Charlie Hebdo or find it amusing to think what happened to its staff modestly beyond the pale. It is not a fine question of literary or editorial merit. The lives of novelists, and even journalists, do not acquire greater moral value simply because their views and writing are compatible with your own view. Their dignity and right to speech exists independently of these matters.

Is it really too much to suppose that blame for this atrocity might be apportioned to the people who did the machine-gunning? This should not be a difficult matter. It really shouldn’t. Nor should recognising, however inadequately, the deaths of these journalists be controversial.

If writers cannot make a stand on this, what can they make a stand upon? Charlie Hebdo was not the first and I fear it will not be the last either. Reality is a bloody business but that’s no reason to avoid trying to look it in the face.

Comments