In May 1940, days after the Dunkirk evacuation, the Churchill defender Andreas Koureas recalls how the great British war leader was, ‘informed by the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, of more dreadful news. Roosevelt had no faith in Churchill nor Britain, and wanted Canada to give up on her. Roosevelt thought that Britain would likely collapse, and Churchill could not be trusted to maintain her struggle. Rather than appealing to Churchill’s pleas of aid – which were politically impossible then anyway – Roosevelt sought more drastic measures.

A delegation was summoned for Canada. They requested Canada to pester Britain to have the Royal Navy sent across the Atlantic, before Britain’s seemingly inevitable collapse. Moreover, they wanted Canada to encourage the other British Dominions to get on board with such a plan. Mackenzie King was mortified, writing in his diary, “The United States was seeking to save itself at the expense of Britain. That it was an appeal to the selfishness of the Dominions at the expense of the British Isles… I instinctively revolted against such a thought. My reaction was that I would rather die than do aught to save ourselves or any part of this continent at the expense of Britain.”’

It’s a touching story about the bond between Britain and Canada, Mother and Daughter countries, a bond which has been notably absent in recent weeks as Donald Trump has employed derogatory and even threatening rhetoric towards his northern neighbour.

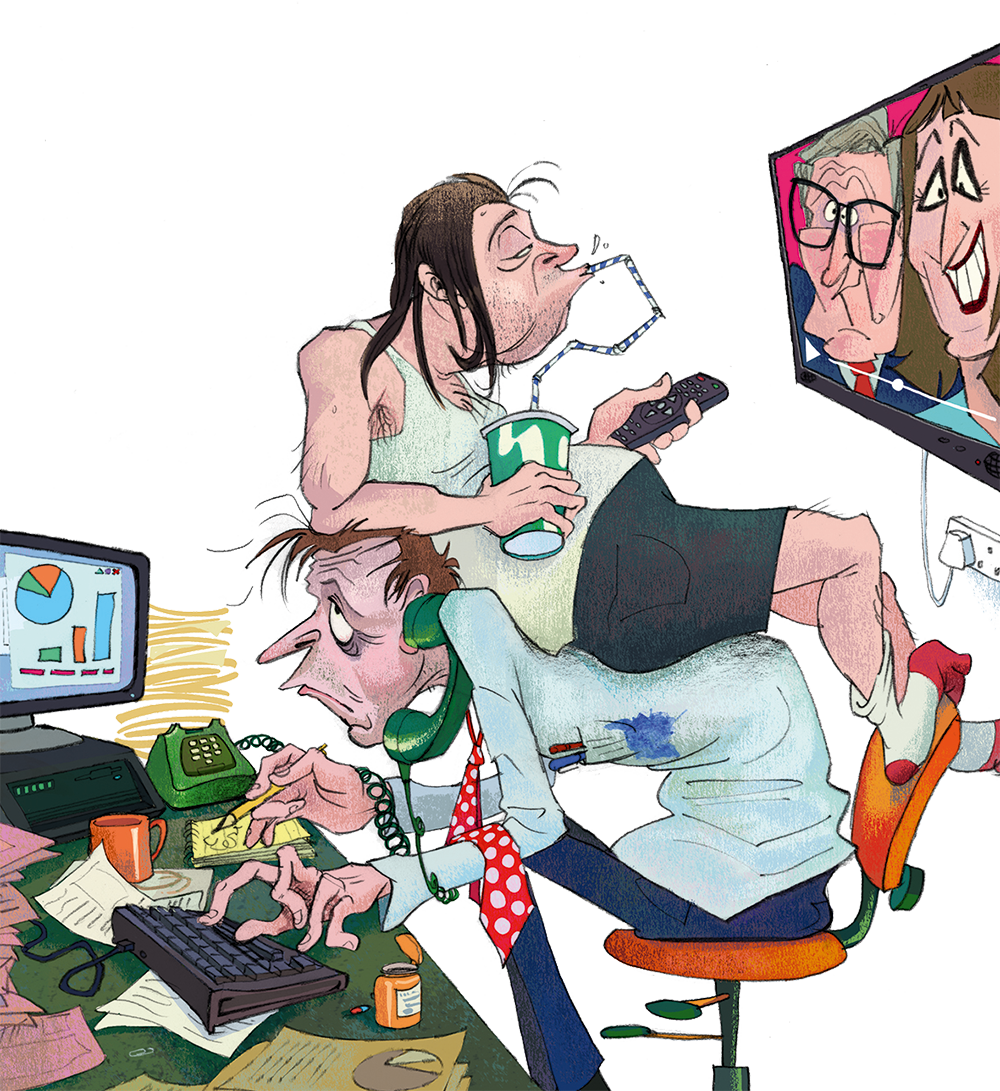

While using the stick of tariffs to enforce greater cooperation on law enforcement, Trump has also referred to the country as the 51st state, called its prime minister ‘governor’ of the ‘Great State of Canada’, and described the border as ‘artificial’. This is obviously a joke, and Trump is a funny man, but it is disconcerting – a bit like hearing the pilot joke about crashing the plane.

The US president’s behaviour has naturally upset a lot of Canadians and helped erode the lead of the Tories there. Voters outside of the US really dislike his bullying tone, which is why Robert Jenrick has been astute in his criticism of Trump’s foreign policy, as well as the administration’s bizarre support for the Tate brothers. Voters want politicians who stand up to the American president, yet it is worth observing that no one in British politics has sought to stand up for Canada, nor made protests to the Americans about Trump’s various insults.

Keir Starmer has notably failed to come to Canada’s defence, even rhetorically, but this is probably good politics, too. He has much to lose by upsetting Trump and Vance, most of all the threat of tariffs which the US leader uses to ensure obedience from his allies.

That’s the way of the world, but once upon a time the British government might have summoned the American ambassador to explain Trump’s comments about annexing Canada. Once upon a time a US trade war against its northern neighbour might have provoked a response from Westminster. Perhaps you’d need to go back some time, before the second world war made Britain dependent on Washington – but the public would certainly have clamoured for a response.

I can’t imagine that many people will recall the 1995 ‘Turbot War’ between Canada and Spain over the issue of fishing rights – which is rather less well remembered than the conflict in which Churchill and King were involved. The right-wing British press were at one point very agitated about it, before their brief attention spans moved onto something more important; presumably what Princess Diana was wearing or which Tory MP was caught in a sex dungeon that week. It was not just because Spanish fishermen were a tabloid bête noire for so many years; papers like the Daily Mail supported the Canadians because they were – their exact phrase – ‘our kith and kin’. This wouldn’t really be true anymore – and that is perhaps a weakness for both countries in an increasingly dangerous world.

Enthusiasts for a ‘CANZUK’ trade agreements point out that, together with Australia and New Zealand, Britain and Canada would form the world’s third largest economy. The bigger you are, the more wary the big beasts are of taking you on. But aside from (mostly) speaking the same global language, what would link these countries enough to risk taking sides in costly trade disputes?

Canada is today the most progressive nation on earth. Indeed it is the only state to have ever claimed to have committed genocide, and if you see a government press conference like this, you just know it can only be one country.

Canada’s runaway progressivism is a feature of smaller Anglophone countries, and perhaps reflects how they forge new identities. The rulers of Scotland, Ireland and New Zealand have all taken these ideas much further than their larger neighbours, even though – based on actual polling surveys – those voters are not more ‘woke’.

But Canada, in particular, seems to suffer from an extreme identity disorder, and almost everything we associate with the country today is the reverse of its historical sense of self. Canada is now seen as a more progressive version of the US, with some added linguistic quirks; it’s what the US could be minus rednecks. In his hugely popular documentary Fahrenheit 9/11, Michael Moore claimed that Canada’s more tolerant, open-minded culture was the reason for its much lower gun crime rate, an example of the sort of bizarre reasoning people will come to if more obvious explanations are not permissible.

Canada’s historical identity was as a homeland for Loyalists who fled the American revolution. It was built on such conservative traditions just as the US was founded on liberalism; heavily settled by Scottish Protestants in particular, it was influenced by Orangeism, which was especially strong in Toronto. The Canadians, famously, fought off a cross-border raid by American-based Fenians; during the Troubles, while Boston Irish provided funding for the IRA, Loyalists raised considerable amounts from their brethren in Ontario.

Canada was also a militaristic society, and in the first world war the Germans especially feared these British colonials, many of whom traced descent from the terrifying Scottish Highlanders. It was so distinct from the United States that, as late as the 1930s, there was even a war plan, Defence Scheme No. 1 for a pre-emptive joint attack by Britain and Canada on the US.

Because Canada had been granted full self-determination over foreign policy in 1931, it was not obliged to enter the war against a Nazi regime which posed no real threat. Its leaders and population were not keen to make further sacrifices; nevertheless, on 10 September 1939, Canada declared war on Germany, and a full 10 per cent of its population served, the vast majority as volunteers. James M. Doohan was typical of them, a young man with quintessentially Celtic features who left his home in Vancouver to fight for the ancestral homeland; shot six times during the D-Day invasion, he survived and went on to became famous to millions as Scotty from Star Trek.

Some 42,000 Canadians lost their lives fighting for the Mother Country between 1939 and 1945. Yet because Canadian identity was linked to the Empire, its rapid retreat after the second world war left them looking for a new one. I’m not sure they’ve really found it.

A new flag was adopted in 1965, replacing the unofficial Red Ensign which emphasised its British heritage. Toronto’s motto – Industry, Integrity, Intelligence – was later changed to ‘Diversity Our Strength’.

This identity crisis has, as elsewhere, been used by those who would like to create a new one. Justin Trudeau once called Canada the world’s first ‘post-national state’ and has helped make this a reality with record levels of immigration, further weakening its British (and French) heritage. As in Britain, where a new multicultural identity makes loyalty to the old subversive, so the old flag is now a sign of extremism.

Britain and Canada are ruled by the same prevailing ideology, ‘Diversity Our Strength’, a phrase which is not just hollow but obviously untrue. Not only does diversity not make a society and state stronger, but as a shared belief between nations it does not create especially strong bonds.

Multiculturalism, tolerance and progressive shibboleths dressed up as a country’s national ‘values’: two countries united by such a thin elite ideology are far less likely to make mutual sacrifices than two nations linked by history, ancestry or religion. It is also the case that Anglophone elites, by adopting all the same progressive beliefs originating in New England and California, make themselves more vulnerable to dominance by the Americans – now with a new Caesar calling the shots. (I think it was the journalist Aris Roussinos who made this observation.)

Realising the threat from the terrifying toddler to their south, those Canadian elites now look to Britain and the Commonwealth for help, but it’s unlikely to be forthcoming. The Commonwealth was always an empty institution, bundling together a load of countries with nothing else in common but a shared history of involuntary rule by another nation. Many of its most powerful members are at best frenemies of Britain or Canada; others use its occasional meetings to extort money over an imperial past now seen in an almost wholly negative light. The most worthwhile bonds from a British perspective were with those countries once settled by their compatriots, the paradoxically named Old Commonwealth (how can Australia be Old and India, that ancient home of civilisation, New?). As much as it would be nice to pretend otherwise, these bonds have less to do with shared values than with ancestry.

The children of immigrants from distant, unrelated lands can become the most patriotic of loyalists; the Churchill admirer I began with is of Greek Cypriot extraction, for example. But when a country’s rulers consciously try to dissolve their ancestral identity, as has happened both in Britain and Canada, then those bonds inevitably fray. In the case of the Mother Country and the Old Commonwealth, that is to our mutual weakness.

It is not just Canada. In recent years, New Zealand seems to have increasingly fallen into the orbit of China, damaging its security relationship with other English-speaking nations. Had they maintained a stronger British heritage, would the Kiwis have been so easy for Beijing to pick off from the other Five Eyes? Perhaps; perhaps not. Similarly, would a Canada with today’s demography and ruling ideology so willingly come to Britain’s aid as it did in 1939? Again, it seems unlikely for one country to make such an enormous sacrifice for another. It’s something people only do for kith and kin.

This article first appeared in Ed West’s Wrong Side of History Substack.

Comments