Is it just me, or is there quite a lot being written about David Bowie at the moment? Of course, there’s the fact that the V&A’s blockbuster exhibition has coincided with the totally unexpected appearance of his first album for ten years. (While putting the exhibition together, the curators could never have dreamed that on the day it opened, a new Bowie album would be number one in 40 countries.) Yet for some cynics on the internet — never hard to find — the recent outbreak of Bowie mania is a simple question of demographics: the media is now run by people who grew up with him, and apparently never get bored of banging on about it. Seeing ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops! Poring over the lyrics of ‘Aladdin Sane’ on the bus back from the record shop! That sort of thing!

Well, I must admit to my fair share of lyric-poring (still word-perfect on ‘Aladdin Sane’, as a matter of fact). I also saw that ‘Starman’ performance, although I can’t help thinking that its instant effect on a whole generation has been mythologised a bit. Even so, I’m not prepared to concede for a moment that the cynics might be on to something.

For a start, both the album and exhibition are great. ‘His best since Scary Monsters’ (1980) has been the traditional verdict on every Bowie album since about 1987. But this time it’s actually true. Bowie’s long-established M.O. is to use what he needs from his obvious influences, discard the rest and twist what remains to his own purposes. On The Next Day his model seems to be what some have called the ‘venerable’ album, where people such as Johnny Cash or Bob Dylan have pondered their mortality. Like them, he includes plenty of references to his own past — always a winner with the fans — and squarely faces up to the tricky business of ageing. (‘Say goodbye to the thrills of life/ Wave goodbye to a life without pain.’) There is, however, almost nothing in the way of mellow, or even melancholy, acceptance — which is why the first single, ‘Where Are We Now?’, was so cunningly misleading. Not only is the album noisy to the point of brash, it’s also a staggeringly self-confident assertion that he was right all along: that his dark 1970s warnings about the general hell-in-a-handcart direction of the world still need to be heard.

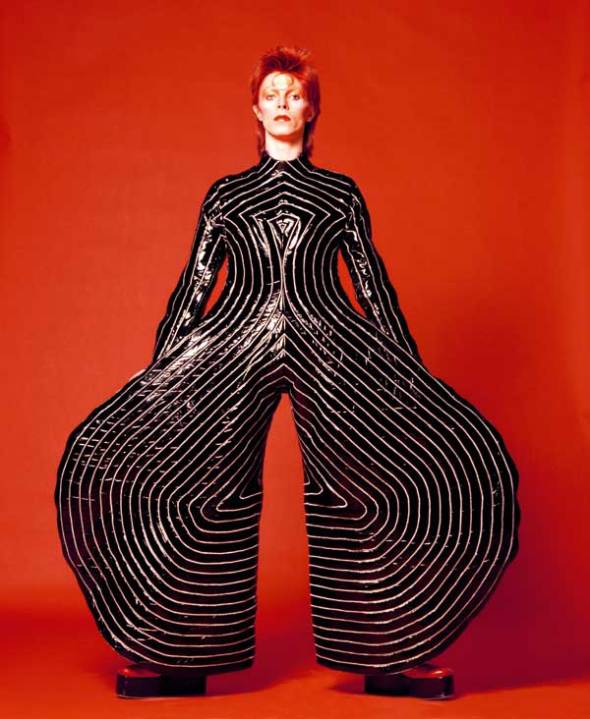

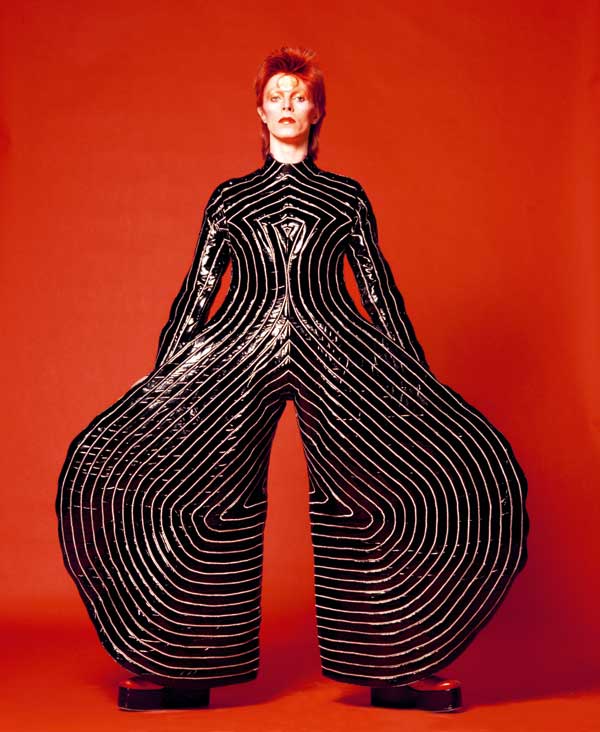

Meanwhile at the V&A, there’s abundant proof that his influence on the culture is hard to overstate — although the accompanying captions do sometimes have a go. (‘David Bowie showed us we could be who we wanted to be.’) After one room on his early life, the rest of the exhibition is more loosely structured, throwing in everything from stage costumes, videos and lyrics sheets to such holy relics as ‘Tissue blotted with Bowie’s lipstick’. The overall effect is a bit like wandering through the man’s head — which is both slightly alarming and completely thrilling.

But the exhibition suggests something else too. One of my favourite pop-music theories is from the broadcaster Danny Baker: that the Beatles are underrated. What they achieved was so astonishing that it’ll still take years before we can fully appreciate it. The same, surely, applies to Bowie.

Between 1969 and 1980 he released 13 albums, nearly all of them brilliant and most of them famously different from their predecessors. At the time, though, it was surprisingly easy to take this for granted — and even possible to resent it. Ziggy Stardust was attacked by several critics, including the usually reliable Nick Kent, on the grounds that a largely unknown singer was grandiosely putting himself forward as the archetypal rock star. Rolling Stone magazine described Diamond Dogs as ‘muddy and tuneless’. And, as someone who’s very sensibly kept most of the rock papers I got as a boy, I can confirm that a mystified Record Mirror called Low a ‘bunch of crap’.

Only 40 years on, with nobody having come close to such an inspired run since, and nobody ever likely to again, are we perhaps getting enough distance to marvel properly — although not to understand how on earth he did it.

The question of when he did it, mind you, might provide another clue to the current revival — because Bowie does appear to be oddly suited to gloomy times. It’s sometimes forgotten that he released his first record in 1964. For the rest of the decade, he experimented with R&B, folk, psychedelia, whimsical comedy and suburban story-telling — all summed up in the 1971 song ‘Changes’ as ‘a million dead-end streets’. Yet the sunny mood of the era never seemed to suit him. Not until 1969 did he make the charts — and that was with ‘Space Oddity’, a song that firmly refused to join in the excitement about the moon landing. And for the next couple of years, that was it. The accompanying album and follow-up single both flopped and, by the early 1970s, Bowie was in danger of being remembered as a one-hit wonder.

But then he got a lucky break: the optimism of the 1960s disappeared. Now the prevailing view of the future was not of utopia, but apocalypse. Needless to say, there are lots of terrific individual songs lamenting the death of the Sixties dream — John Lennon’s ‘God’, The Who’s ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’, the Stones’ ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’. Bowie did one himself: the almost unhinged ‘Cygnet Committee’ (my candidate for his most criminally overlooked track) on the album now known as Space Oddity. Yet he was also able to build an entire career on the new mood.

Take his Seventies anthem ‘All the Young Dudes’ — written for Mott the Hoople in 1972. There, it’s the narrator’s older brother who’s ‘back at home with his Beatles and his Stones’. The children of the 1970s, by contrast, ‘never got it on with that revolution stuff. What a drag. Too many snags.’ (And if there’s a pithier summary of the difficulties of world revolution than ‘too many snags’, I can’t think of it.) The same year, Ziggy Stardust opened with the news that the world would end in five years, and closed with the suicide of the main character. ‘I’m an awful pessimist,’ Bowie confessed, perhaps unnecessarily, in 1973 — and later described Diamond Dogs from 1974 as ‘my usual basket of apocalyptic visions… terribly miserable’.

Admittedly, another thing that’s sometimes forgotten is that Bowie’s greatest era of commercial success was the 1980s. Ever since, though, he’s dismissed the period as ‘my Phil Collins years’. So, can it be a coincidence that his creative return to form has come with the world well on its way to 1970s levels of apocalyptic anxiety? Or that the new album starts as it means to go on — with a ‘baying crowd’ who ‘can’t get enough of that doomsday song’?

Comments