The first rule in John Updike’s code of book reviewing is: try to understand what the author wished to do and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt. I should therefore not blame Laurence Leamer for failing to capture in Capote’s Women any sense of what made Truman Capote irresistibly attractive to all sorts of people – rich, poor, male, female and especially to his flock of high-society swans, the women of Leamer’s title. Nor should I blame him for failing to identify what made Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood both beloved by critics and hugely popular. I can’t blame Leamer, because what he has attempted is a book of undiluted gossip, and that’s what he has achieved. ‘Submit,’ Updike urges us, ‘to whatever spell, weak or strong, is being cast.’ I submitted – and felt like I was caked in slime.

Capote was warned that spilling his swans’ secrets would be a disaster

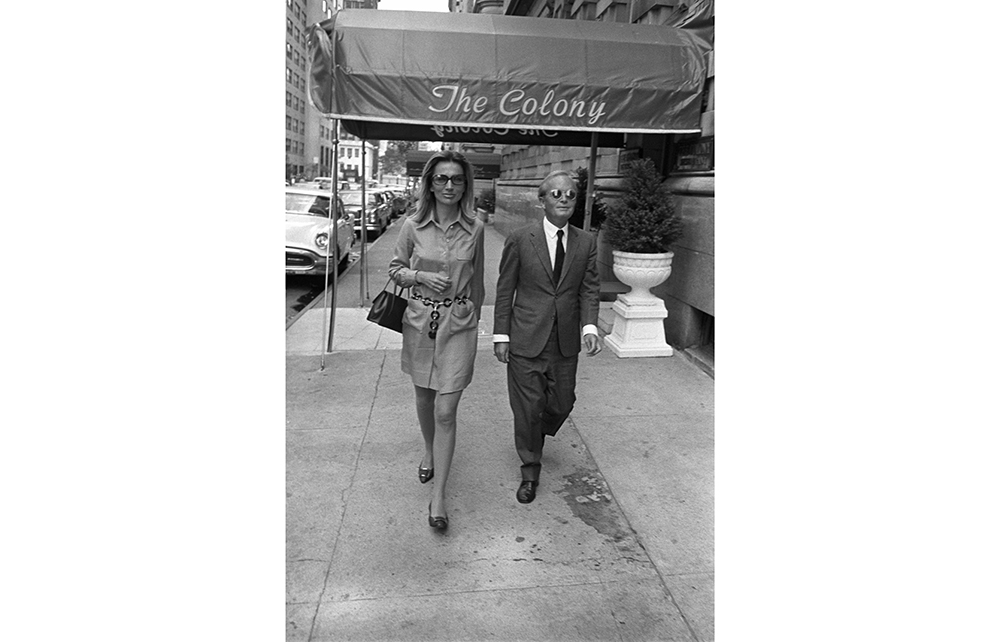

There is a plot of sorts. Capote made his name against the odds, thanks to hard work, charm, compulsive self-promotion, social climbing and true literary genius. All his swans – Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness, Slim Keith, Pamela Harriman, C.Z. Guest, Lee Radziwill, Marella Agnelli – were blessed with great beauty, grace, style and varying degrees of intelligence. Most were much- married. Not one of them possessed a talent that could survive outside the small pond of extreme privilege and extravagant riches in which they paddled.

Having collected his swans and celebrated his success a few months after the triumphant publication of In Cold Blood with the epochal Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, Capote began a long slide into middle-aged bloat. The combination of alcohol and drugs and constant high-society schmoozing is apparently inimical to serious literary endeavour. His plan to arrest that slide was to write a ‘Proustian’ novel about Babe Paley, Slim Keith etc, called Answered Prayers. Chapters of this unfinished roman-à-clef (memorably described by Picasso’s biographer John Richardson as ‘shit served up on a gold dish’) were published in Esquire in 1975 and 1976 and caused a sensation – not in a good way. In addition to being unfinished and godawful, the novel was a vicious, unprovoked betrayal of the glamorous women Capote claimed to love. Babe Paley was dying of cancer when ‘La Côte Basque, 1965’, the most egregious chapter, was published, full of poisonous revelations about her marriage to the media mogul Bill Paley.

Capote was warned by Gerald Clarke, his future biographer, that spilling the secrets of his swans would be a disaster; that they would recognise themselves and ostracise him and that he would lose his best friends. ‘Naaaah, they’re too dumb,’ Capote said. ‘They won’t know who they are.’

Leamer gives us potted biographies of the swans, and a wiki chronicle of Capote’s career. According to Updike, reviewers should provide enough direct quotation to give the reader a taste of the book. Here’s Leamer on Gloria Guinness:

From the day 38-year-old Gloria married Loel, she had a single-minded goal: to sit atop the swirling social world that she’d gained entry to just before the second world war, and which was again picking up steam now that the war was over. Although 44-year-old Loel was a member of the British establishment, the Mexican-born Gloria had no European social background. And she had, of course, trafficked with Nazi war criminals; that was a stain that was hard to wash off, no matter how beautiful and accomplished she was.

Leamer proceeds to forget all about that ‘stain’ – or maybe washing it off wasn’t so hard after all.

Two of Capote’s women friends (neither of them particularly swanlike) were brilliant and talented. Katharine Graham, the publisher of the Washington Post, was the guest of honour at the Black and White Ball. Leamer has almost nothing to say about her. Nelle Harper Lee lived next door to the young Truman in his hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. Later, while he was researching In Cold Blood, she was his indispensable assistant. She is of course world famous as the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, published in 1960. Leamer ignores her, too, though he does provide this baffling glimpse of their childhood friendship: ‘When Truman decided he wanted to be a writer and started pecking away diligently on his typewriter, he inveighed Nelle to write too.’ That’s just one of several of the book’s more unfortunate sentences. My favourite is a description of Perry Smith, eventually executed for the crime which In Cold Blood anatomises: ‘The uneducated murderer was a vociferous reader, obsessed with building up his vocabulary.’

‘Better to praise and share than blame and ban,’ says Updike. ‘If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines.’ Easy! George Plimpton’s Truman Capote (1997) is a rollicking oral history of the author’s fabulous rise and dismal fall; and Gerald Clarke’s Capote (1988) is lively, intimate, meticulously researched, clear-eyed and authoritative. Anything you might want to know about Capote’s women – including the brilliantly talented ones such as Graham and Lee – can be found in Plimpton and Clarke. Both books delight and instruct.

Comments