Actors are easily bored on long runs. Phoebe Waller-Bridge once revealed that she staged distractions in the wings to amuse her colleagues. On the last night of Hay Fever, egged on by another actor, she bent over ‘and showed [her] arsehole’ to the on-stage actors.

Nabokov’s plays are seldom performed. But he was alive to middling, mediocre dramatic clichés, fashions long-forgotten, but invaluably preserved in his 1941 lecture ‘The Tragedy of Tragedy’: ‘The next trick, to take the most obvious ones, is the promise of somebody’s arrival. So-and-so is expected. We know that so-and-so will unavoidably come…’ This is the lost convention, the stand-by that Beckett was frustrating in Waiting for Godot – with its tedious announcements and its adamantine disappointment.

John Osborne was a jobbing actor and therefore intimately irritated by the conventions of repertory drama. In Epitaph for George Dillon, co-written with another actor, Anthony Creighton, Osborne super-sizes the Act One curtain line. It is announced that George Dillon will be arriving as a temporary lodger. He arrives. It is intimated that he will replace Raymond, a son who has been killed in the war. He is exceedingly polite. But his curtain line, as he contemplates a framed photograph of Raymond, is ‘You stupid-looking bastard’.

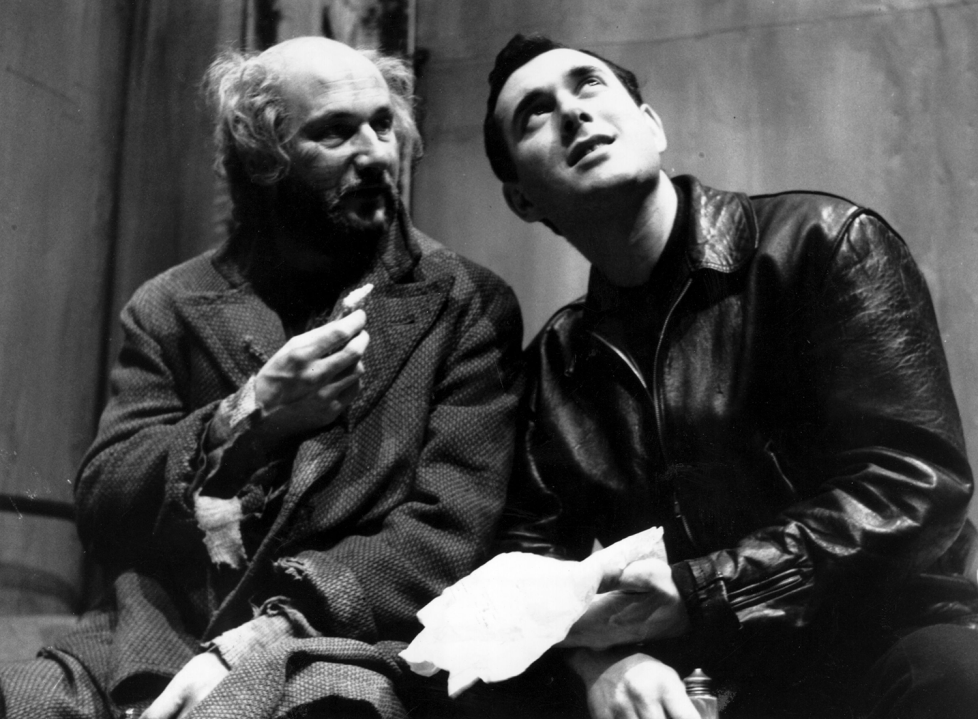

As David Baron (his stage name), Harold Pinter was another disaffected thesp. Hence his brusque impatience with dramatic convention. The Caretaker begins by violating convention:

MICK is alone in the room, sitting on the bed. He wears a leather jacket.

Silence.

He slowly looks about the room, looking at each object in turn. He looks up at the ceiling, and stares at the bucket. Ceasing, he sits quite still, expressionless, looking out front.

Silence for thirty seconds.

Thirty seconds of silence in the theatre is an eternity. And this second silence follows on the initial silence. Then Mick exits. Without saying a word. An unusual, irregular opening. When Act One ends, we expect the act-division to cover an omitted passage of time. But Act Two begins ‘A few seconds later’.

The Room begins as a two-hander – a bizarre one-handed two-hander, in which the wife drivels on, unstoppably. The husband, Bert, says nothing until the very end of the play – an extreme version perhaps of the radio comedy Take it from Here, where the young couple, Ron and Ethel, displayed the same imbalance, Ron’s dialogue being restricted to ‘Yes, Eth’. Ron being short for Moron.

The Homecoming has an important stage direction describing the set. The wall between the sitting room and the staircase isn’t there. The audience assumes this is an exploded view, a stage convention, so we can see what would otherwise be hidden. However, as Lenny tells us later, the wall has actually been knocked through. The imaginary and the real are confused, as they are for most of the play, until it becomes clear that the men in the play are acting out a communal fantasy – a sexual fantasy trailed by Max, the patriarch, when he is guying his homosexual brother, Sam: ‘When you find the right girl, Sam, let your family know, don’t forget, we’ll give you a number one send-off, I promise you. You can bring her to live here, she can keep us all happy. We’d take it in turns to give her a walk round the park.’ This prolepsis is long before the arrival of Ruth and Teddy, long enough for the audience to forget it. Ruth is a prostitute. But for most of the play we aren’t certain. The confusion over the wall is emblematic of this overall instability.

The Dumb Waiter – two killers waiting for their victim – derives from Hemingway’s story ‘The Killers’. The hyper-banal is invested with menace. Hemingway’s title makes even the diner menu toxic: ‘chicken croquettes with green peas and cream sauce and mashed potatoes.’ Banal, except that the men eat with their gloves on. ‘In their tight overcoats and derby hats they looked like a vaudeville team’ – if they didn’t look so much like gangsters, George Raft or Jimmy Cagney. Food and fear, a telling zeugma.

In Pinter, orders for scampi, for soup of the day, liver and onions, jam tart, arrive via the dumb waiter, defunct but still active – like a moribund stage convention. Here we have the classical convention of the deus ex machina, the god lowered in some sort of box who intervenes at a play’s end to resolve all difficulties and provide solutions. But instead of instructions, there are customer ‘orders’. It is significant that the stage directions refer to the ‘box’: ‘The box descends with a clatter and bang.’ Not ‘compartment’ or ‘shelf’.

Pinter’s play knows it is a play. Just before the dénouement, Gus and Ben rehearse:

BEN: When we get the call, you go over and stand behind the door.

GUS: Stand behind the door.

BEN: If there’s a knock on the door you don’t answer it…

What transpires, however, is nothing like the rehearsal. Gus stumbles in looking more like a victim than an executioner: ‘He is stripped of his jacket, waistcoat, tie, holster and revolver.’ A reversal of the rehearsal. Nothing is resolved. Anyone for menace?

Comments