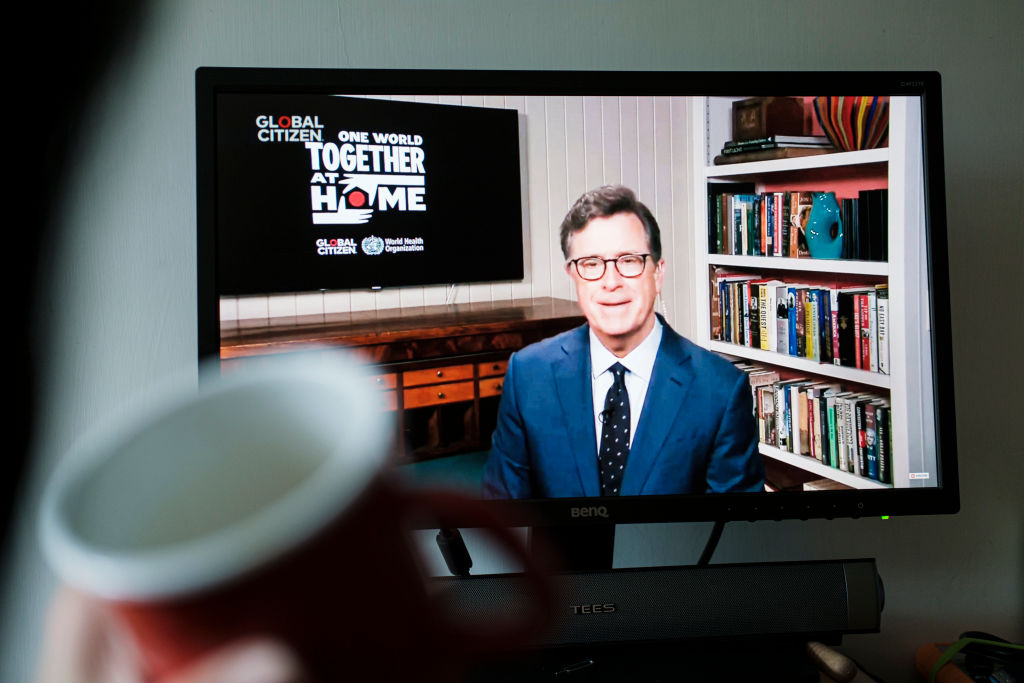

You don’t need to know any more about Stephen Colbert than that he is an American political broadcaster and satirist who hosts ‘The Late Show’ on the CBS television channel, which makes him something of a US household name. Last week, after Donald Trump had given his embarrassingly rambling non-concession speech in the White House briefing room, Colbert made some headlines himself – not just for the diatribe he delivered, which included calling the US president a ‘fascist’, but for ‘choking up’ (The Hill) as he introduced the item.

This is how the website’s Marina Pitofsky reported it:

‘Colbert during the introduction to his show looked down while showing emotion, and then added, ‘What I didn’t know is that it would hurt so much…..That office means something and that office should have some shred of decency.’

There was quite a lot more in the same vein. Colbert was, it should perhaps be added for readers on the UK side of the Atlantic, firmly in his political commentator, rather than satirical, mode.

Some might say that it is a legacy of Watergate. But American journalists have a tendency to take themselves very, very seriously. Not, I hasten to add, that their British counterparts treat their – our – calling with unrelieved levity; it is not for nothing we call ourselves the Fourth Estate and do our best to hold power to account. For the most part, though, we do what we do without the sanctimoniousness that seems to attach to so many of our transatlantic colleagues.

Anyone who has covered a UK-US summit meeting will know that some differences are stark. When the two leaders enter the room, the White House press corps, to a man and woman, spring from their seats out of respect for the Commander-in-Chief. Meanwhile the British press corps will be shuffling around, in two minds about whether to stand or not, until shamed or chivvied into reluctantly rising to their feet.

All right, so a US president is head of state, whereas a UK prime minister is not, and we would probably stand for the Queen, even in today’s less reverent age. But at a summit press conference you have two national leaders, each elected, each answerable to their voters, each about to face the same sort of questions from the same journalists.

It is this very American deference for the office that led Colbert to the verge of tears, something that you could not imagine – at least I could not imagine – being replicated by any British journalist. We might show anger, even contempt, yes. But tears? No.

Nor could you imagine any major British news broadcaster – public service or commercial – cutting away from an occasion such as Trump’s White House meanderings last Thursday night, as several US networks did. Here was the president giving his first formal response to the possibility that his bid for re-election had failed, and he was silenced. Why? Not because his performance was so embarrassing that the broadcasters wanted to save him from himself, nor because they could see that viewers were becoming bored, but because the president was, in their words, ‘lying’, and they refused to carry his ‘lies’ about election fraud over their airwaves.

Whether that was a good call or not, I leave you to judge, but it marks a big difference between our media culture and theirs. It also helps to explain some of the particular difficulties that US journalists have faced with the Trump phenomenon, and the passions that have been in play.

The soul-searching began even before Trump was inaugurated, with near-panic in some journalistic circles about how to cover a president who diverged so far from the norm, to the point of seeming quite unfit to hold the highest office. Were they to be observers or players? Print journalists were especially exercised, as the press in the US prides itself on its reputation for objectivity and balance, while it is the broadcast media that are politicised – in a mirror-image of the media landscape in the UK.

This quandary had little resonance in the UK, because for British journalists, politicians up to and including national leaders are fair game – some would say, too much so. The less fit for office a politician demonstrates himself or herself to be, the more the print media and now the social media let rip and enjoy themselves (within the limits of the libel laws). In the US, it is different.

With Trump, the media faced a conflict between two imperatives: respect for the office and their duty, as they saw it, to expose the flaws of its current holder. How far that duty to expose was underpinned by a more visceral hostility, even disdain, for a man who was clearly ‘not one of us’ can be debated. One way or another, though, the New York Times and CNN, among others, elevated themselves into something akin to an extra-Congressional opposition – and Trump, being Trump, responded in kind. The result was a series of extraordinary encounters at presidential press briefings, with tweeted insults, suspended credentials and walk-outs.

Still, the media remain split about how far they should take sides. And you could argue that the reason why the presidency of Donald Trump confronted US journalists with such a challenge was precisely because they take themselves and their responsibilities so seriously. That is laudable in its way, but from the European side of the Atlantic, it is hard not to feel that a little less deference to the presidency, a little less soul-searching about objectivity, and – dare one say – even the slightest touch of humour, might have been at least as effective in telling truth to power. Viewers of ‘The Late Show’ might also have been spared Stephen Colbert’s tears.

Comments