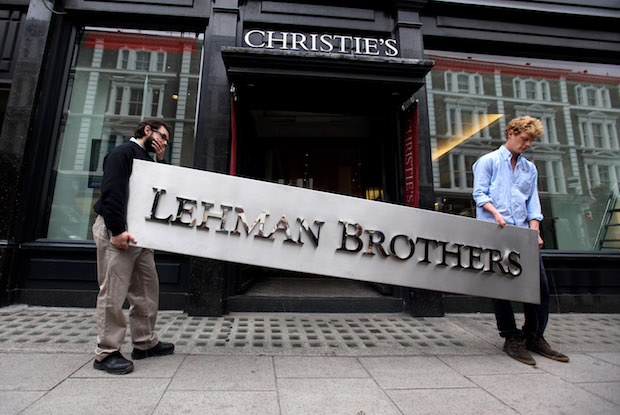

With September marking a decade since the Lehman Brothers implosion, stand by for a slew of economic retrospectives. Any meaningful analysis, though, needs to get beyond historic balance sheets and plunging share price graphs — however dramatic the data.

For the most significant impact of the biggest financial and economic upheaval since the Great Depression has been the growing loss of faith in western liberal capitalism. Politics has been upended by the 2008 crisis — doing much to explain Trump, Corbyn and the broader shift away from centrist parties towards extremes.

The demise of Lehmans, a once-impregnable investment bank, exposed a US financial sector riddled with chronic debts and fraud. That sparked a peak-to-trough plunge of more than 40 per cent across western stock markets — the deepest since the 1929 Wall Street crash.

The ensuing recession saw global trade shrink by a fifth, costing the world economy some $10 trillion (over a sixth of 2008 global GDP). In 2009, total world output contracted in real terms, after inflation, for the first time in history.

Unlike previous meltdowns, the ‘sub-prime’ collapse was an economic trauma of the western world’s own making. There was no external oil embargo, no emerging markets crisis, no all-consuming war. It was caused largely by reckless bankers on both sides of the Atlantic taking advantage of increasingly lax regulations. The money men were facilitated by politicians who were, at best, misguided and often chasing campaign donations from an increasingly powerful financial services industry.

During the run-up to 2008, by allowing banks to hold less capital against their assets, while setting interest rates too low, policy-makers encouraged big financial institutions to take on huge debts and pile in to ever more risky assets. Old-fashioned, prudent bankers were sacked, replaced by youngsters who were happy to bend, and in some cases break, the law.

To keep the party going, regulators then permitted large banks to parcel up loans and sell on the exposure, creating markets for asset-backed securities, credit derivatives and other deliberately opaque financial products. Able to offload credit risk, such banks no longer cared who they lent to — sparking an orgy of speculation that spread exposure to a bloated, crash-prone US housing market across the globe.

That, in turn, threatened the integrity of the entire western banking system, including the cash balances of ordinary firms and households — not least because, after particularly intense Wall Street lobbying, President Clinton had ditched the Depression-era rule that kept taxpayer-backed deposits out of the hands of risk-taking investment banks. Once that vital divide was breached with the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, a crash was inevitable. Further Bush-era deregulation, copied in London and elsewhere, just added fuel to the fire.

Although the 2008 collapse was serious, the crash alone hasn’t caused such widespread political anger, provoking so many moderate voters to question ‘the system’. Financial crises aren’t unusual, happening every 10 to 15 years or so. What has grated about the sub-prime debacle, the really galling aspect, has been the weak and deeply counter-productive policy response — which not only prolonged the post-2008 economic fallout but has also left us far more vulnerable when the next crisis comes.

The combination of continuing lax regulation and the endless central bank money-printing we’ve seen means that banks remain too big to fail and those owning assets, including the same bankers and institutions that caused havoc, have effortlessly become even richer. That tears at the social fabric. Capitalism stands or falls on broad public consent. And, as wealth inequality has spiralled since 2008, with the financial behemoths and corporations generally becoming more not less powerful, such consent has started to slip.

It’s a source of widespread public outrage that while the crisis destroyed countless businesses and millions of jobs, the fraud that preceded it has gone largely unpunished. We’ve seen some convictions, but many more cases remain outstanding. The banks, meanwhile, have generally reached out-of-court ‘settlements’, paying fines that sound hefty, but are just a fraction of the massive state bail-outs they received.

There is much public dismay, too, about quantitative easing. The US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have driven a worldwide QE expansion totalling more than $20 trillion, injecting money into banks and financial markets with no democratic checks or balances.

While drastic action was justified in the months after the Lehmans collapse, such emergency measures soon morphed into a lifestyle choice. Ongoing QE has powerful friends, pumping up financial markets and other asset prices. But the related ultra-low interest rates — negative in real terms — have seen pensioners and other savers suffer badly.

QE-driven house price rises have put home-ownership beyond the reach of millions of young professionals — not least in the UK, causing a decisive swing towards Corbyn. Outrage at the Fed’s money-printing fuelled the rise of the right-wing populist Tea Party movement, paving the way for President Trump. The ECB’s QE programme sparked the creation of Alternative für Deutschland, the far-right party that, despite being founded only in 2013, now forms Germany’s biggest opposition party.

And instead of promoting a surge of lending to firms and households, much QE cash has remained dormant, with moribund banks using it to shore up their balance sheets. So the growth QE was meant to generate has barely happened. The US economy spluttered for years after its post-Lehmans downturn, with the UK registering its slowest recovery from recession in more than a century.

Many western governments imposed post-crisis ‘austerity’ measures to ward off financial ruin. The combination of stagnating wages, and some targeted spending cuts, drove much public discontent. Despite the rhetoric, though, both public and private borrowing actually ballooned.

There is now $63 trillion of sovereign debt outstanding across the world, with total debt at $237 trillion — a full $70 trillion above pre-crash levels. The US public debt ratio has rocketed from 65 per cent of GDP in 2008 to 105 per cent today, with the UK equivalent up from 40 to 87. In the eurozone, Italy’s public debt now exceeds 130 per cent of national income, a third higher than in 2008 — and is threatening to cause a eurozone implosion, which would prompt further populism on the Continent.

Many new economic challenges have arisen over the past decade, of course. The ‘advanced’ economies’ share of global GDP has shrunk from more than 70 per cent to well below 60 — a long-term trend, accelerated by the sub-prime crisis, that has intensified global competition. Technological progress is threatening mass unemployment, just as the western world’s demographic transition puts public finances under further strain.

But the 2008 financial crisis, and the policy response to it, have radicalised millions of mainstream Western voters, as the ultra-rich have prospered at the expense of the ‘squeezed middle’ — with many previously comfortable families now fearful. The crisis appeared to embolden the financial elite, demonstrating its control over western governments.

Since then, big businesses have become even more powerful — and not just banks. From airlines to energy companies, telecoms to house-building, many sectors have become more concentrated. Consumers have faced less choice, poorer service and high prices — adding to the ‘them and us’ grievances that drive broader discontent.

Global stocks markets, pumped up by QE, are soaring, with valuations flashing red. Current ‘late-stage, credit-cycle dynamics’ and ‘investor excesses’ are worryingly reminiscent of 2008, according to the International Monetary Fund. Yet, with interest rates at rock bottom and state debts historically high, when the crash comes, there is scant scope to soften the blow.

Of the 30 too-big-to-fail banks before the crisis, three-quarters are now significantly bigger, according to Standard and Poor’s rating agency. Bank regulation remains weak and there is still no reinstatement of the Glass-Steagall separation of commercial and investment banking — so when reckless investment banks fail, ordinary deposits will be vulnerable, ensuring governments come running once more. There has been righteous populist anger since 2008 — and there’s much more to come.

Comments