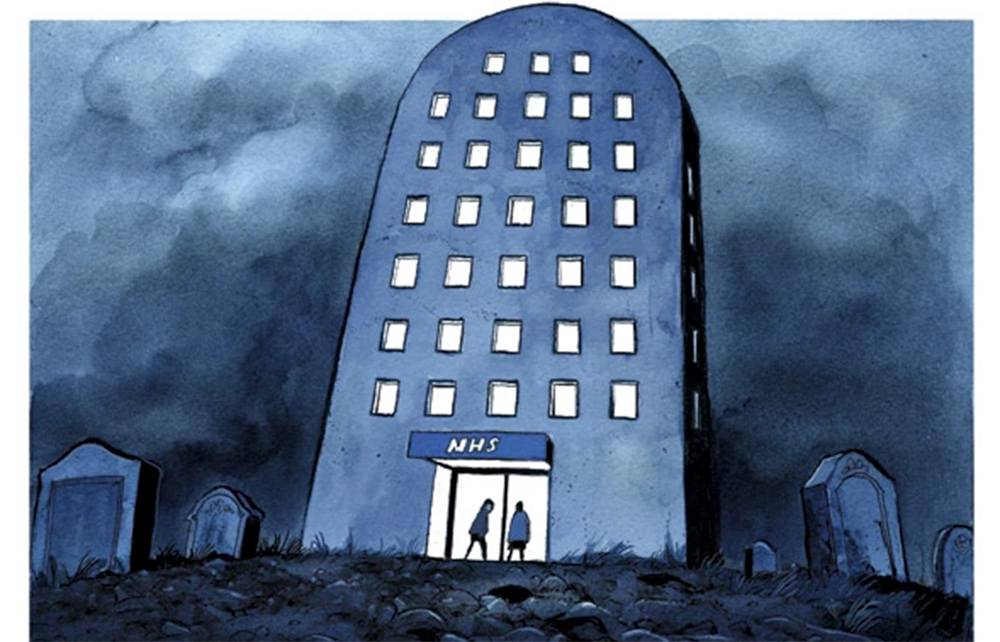

Old people are being stranded in hospital, diagnosed with terrible diseases but unable to recover enough to go home. Dr Adrian Boyle, the new president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, has said that NHS hospitals ‘are like lobster traps… easy to get into but hard to get out of’.

Might it not be better for some if they’d never gone, or at least never been told exactly what was wrong?

In C.P. Snow’s 1951 novel The Masters, the Master of a Cambridge college is ill. People seeing his bedroom light on night and day wonder how long he has left, but the question never occurs to him because he hasn’t been told he has terminal cancer and so believes he is recovering and will soon be back at the helm. Those Fellows who know the truth are appalled at the deceit but his family are adamant that he should remain in happy ignorance until the end.

This scenario, impossible now, was still usual in the 1970s, when my mother developed bowel cancer. She’d had diarrhoea for many weeks, and her weight dropped from eight to five stone, but it wasn’t until she was passing blood steadily that she consulted her GP, who sent her straight to an oncologist outpatient clinic. I drove her, in spite of protestations about the bus being perfectly satisfactory. The consultant was on an emergency so she saw his registrar and in the waiting room I could hear their conversation from a curtained cubicle.

‘You must come in for an operation. I’m getting you an urgent admission.’

‘What’s wrong with me, doctor?’

Today she would not have had to ask but even if the GP had stayed silent, the registrar would have replied: ‘You have advanced bowel and rectal cancer.’

Instead I heard: ‘You have some ulcers in your back passage, but Mr Black can remove them. Nothing to worry about.’

She emerged with a big smile. I was familiar enough with cancer symptoms to know the doctor had lied but was relieved he had. My mother’s generation – she was born in 1909 – never used the word ‘cancer’: it was a cursed word and speaking it might well bring it upon you. As a child, I only heard the whispered letter ‘C’.

The main cancer treatment in 1971 was surgery. Chemotherapy was unknown and although radiotherapy had been used since 1935 it was not suitable for every case, including my mother’s.

The surgeon found her disease so widespread that he had to remove more than half her bowel, one kidney, her womb and ovaries and much surrounding tissue. He spoke to me afterwards. ‘I had to stop or there wouldn’t have been anything left.’

‘Does she know?’

‘What I removed? Yes. That it was cancer, certainly not. How would that benefit her? It will come back of course, but I hope I’ve bought her some time.’

He had bought her three-and-a-half years. She obeyed his instructions to eat well, take exercise and not fret. Within 12 months she had put back on all the weight, was walking three miles a day, coping with a stoma and singing the surgeon’s praises. She looked and felt fit and above all, was supremely unworried. So far as she was concerned, it was behind her.

Then a friend, newly diagnosed, wrote to my mother asking for advice: ‘It will be so helpful to know your experience of cancer.’

The C-word had been not spoken but written, which was apparently even worse. Its curse became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The disease raced back and she declined from then on, sinking into a depression so deep that she lost the power of speech, dying two months later.

When did not telling become telling? Doctors now share every medical possibility, from definite diagnosis to remotest chance. Were they guilty of medical negligence back then? Or did they remain silent in what they believed was a patient’s best interest and to encourage peace of mind? Is today’s approach all to do with the fear of being sued?

Recently a friend’s baby had a fast-rising temperature, and was pale and floppy. After examining him, a junior doctor gave the poor mother a list a mile long of what he might possibly have, including Covid and a cold, but she was too upset to sort it out. She just rang her husband at home and through hysterical tears said: ‘He’s got meningitis.’

I think I’m happy to know the truth about myself but many are not. Is it absolutely essential for doctors to share grim prognoses with every patient? Can ignorance not still sometimes be bliss, as it was with my mother until someone let the cat out of the bag?

Comments