Burkina Faso’s transitional legislative assembly passed a bill this week to outlaw homosexuality – making it the 32nd out of 54 African countries to criminalise homosexuality. The legislation, enacted under the military junta-run country’s new Persons and Family Code, penalises ‘behaviour likely to promote homosexual practices’ with prison sentences up to five years. The move is part of Burkina Faso’s military leader Ibrahim Traoré’s vocal crackdown on ‘western values’.

Burkina Faso has now become the 32nd out of 54 African countries to criminalise homosexuality.

Neighbouring Mali, also run by a military junta spearheaded by Assimi Goïta, passed a similar ban in November. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Abdourahamane Tchiani’s Niger, which together formalised junta-ruled Alliance of Sahel States (AES) in 2023 following military coups in the three countries, are among 20 or so majority Muslim countries in Africa, many of which have bans in place for the LGBT community. While the likes of Egypt and Djibouti don’t have explicit anti-LGBT laws, persecution against the community is carried out under morality codes. Mauritania, Nigeria, Somalia, and Somaliland are among the dozen states that have codified the death penalty for homosexuality, with around 20 other Muslim-majority countries imposing violent sharia penalties, such as flogging, or lifetime incarceration.

Around 30 Christian-majority states around the world criminalise homosexuality as well. In Africa, Uganda has codified the death penalty for ‘aggravated homosexuality’ via its Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023, which includes same-sex activity involving the vulnerable members of the community such as those underage, senior citizens, or persons with disabilities. Yet while the correlation between Islamic scripture and anti-LGBT violence in the Muslim world is rarely the subject of deliberation among western LGBT activists, Christian homophobia and the influence of missionaries is vocally condemned in African countries such as Uganda, Ghana, Tanzania, or Zambia. Even in Kenya, once a refuge for LGBT asylum seekers despite its own anti-gay restrictions, further legislations are being considered that would increase the clampdown against the LGBT community.

In these former European colonies, and others, anti-gay laws are often viewed as ‘remnants of colonialism’. Even so, unlike numerous other African countries that adapted colonial penal codes post-independence, neither Burkina Faso nor Mali previously had laws in place targeting homosexuality. In fact, despite being Muslim-majority, neither has invoked Islamic sharia either, with these regimes suggesting that their anti-LGBT orientation is more a defiance against western imperialism.

Perhaps as a result, rights groups in the West – which often speak of the discrimination faced by members of their communities at home – are more reticent about those facing death and violence in various countries in Africa. African activists have complained that they are ‘exploited for clout’. Others have accused western-origin groups of effectively abandoning Africa and showing a complete disregard for democracy in Africa. Global ‘pan-Africanist’ groups have been accused of keeping quiet about crackdowns enacted by African leaders, simply because they package the persecution of their people in an ‘anti-West’ wrapping.

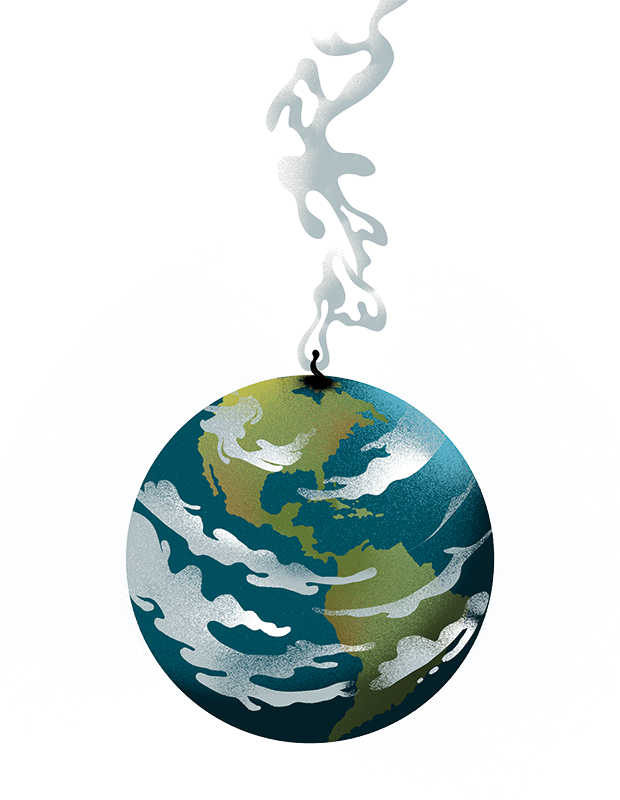

As African leaders against ‘foreign powers’ violently police the personal lives of their nations, jihadist outfits such as the Al-Qaeda-affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and Boko Haram are spreading across West Africa. They are united by their animosity against the West and oppression of the LGBT community.

Gay and lesbian Africans increasingly live in fear. Yet western activists – willing to make plenty of noise about certain issues – are staying quiet.

Comments