America is known for its lobbying industry, from PR shops and law firms to former federal officials acting as agents for tyrants. K Street is not just a Washington DC address, it is a metonym for the business of influence.

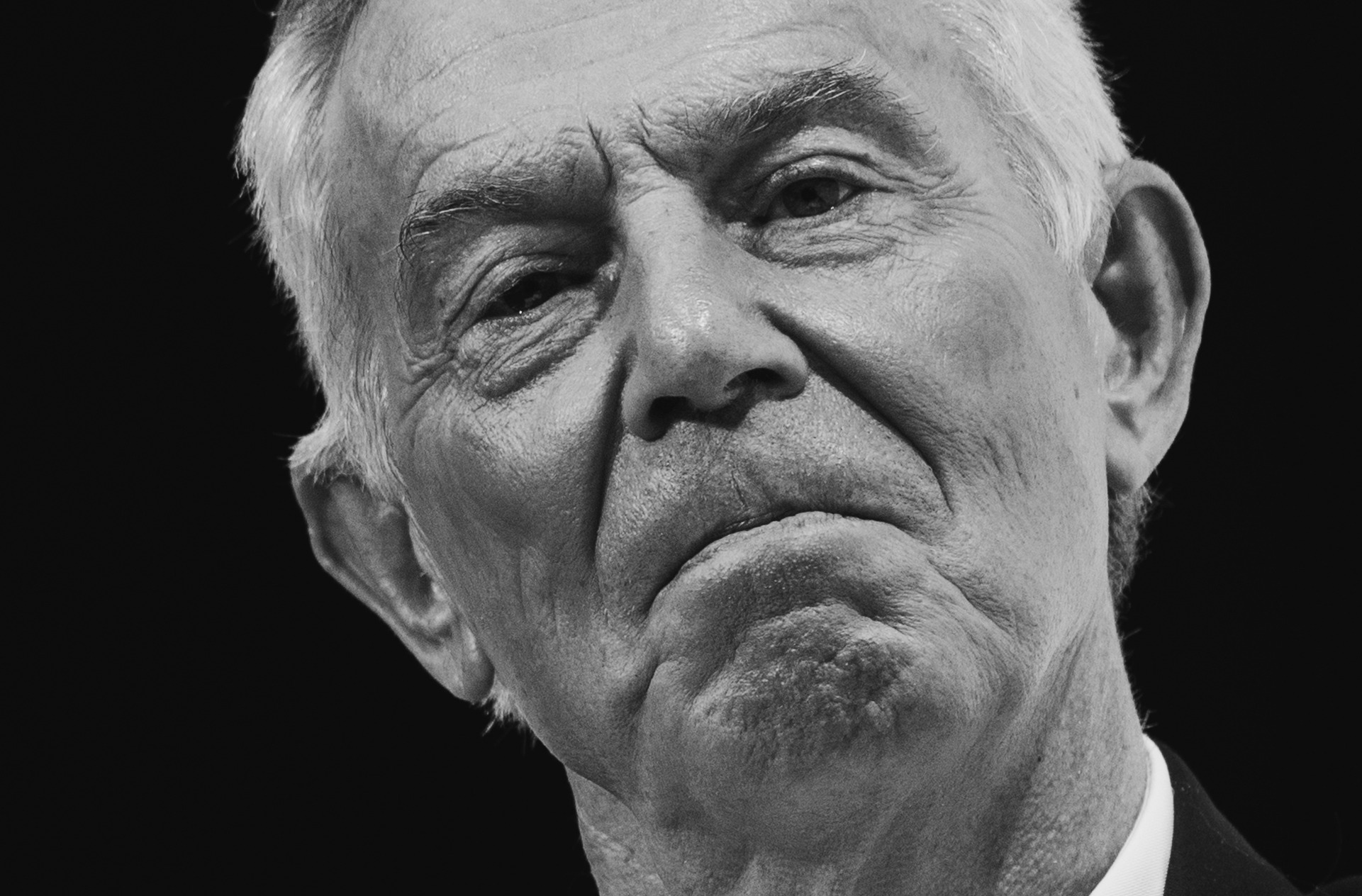

London too has plenty of consultancies and PR agencies gleefully signing up autocratic clients. There is, however, one key difference. While the US industry has many fathers, in the UK there is one man who single-handedly launched the modern lobbying industry, laundering the reputation of tyrants, and showing others how much money can be made in the process: Tony Blair.

Blair is also influential in Keir Starmer’s Labour party, with multiple former Blairites recently signing up as Starmer’s special advisers. These figures include not just Matthew Doyle – Starmer’s new director of communications, who was Blair’s own special adviser as prime minister – but also people like Varun Chandra, who helped launch Blair’s post-PM career and who, according to the London Review of Books, also recently joined Starmer as a special adviser on business and investment. Perhaps hiring so many former Blairites is understandable, given Labour’s electoral record over the past half century. But Blair’s record since leaving office in 2007 is also worthy of attention.

Over and again, Blair and his network helped autocrats open doors in London

There was, for instance, Blair’s decision to cozy-up to the decades-long dictatorship in Azerbaijan – which was most recently responsible for the 2022 ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh. The regime’s bloody-mindedness was clear even before this, with the incarceration of political opponents and reports of torture. But that never seemed to bother Blair, who made fantastic sums blessing things like methanol plants in Azerbaijan and building ‘close links’ with the country’s ruling dictator. All of it culminated in Blair being hired in 2014 as an advisor on an Azeri gas pipeline – which just so happened to be the ruling dictator’s ‘pet project’.

It is a similar story in Kazakhstan. For the first three decades of Kazakhstan’s independence, the country struggled under an ogreish, kleptocratic strongman named Nursultan Nazarbayev. Like regimes in places like Russia or Belarus, whatever freedoms Kazakh citizens enjoyed in the immediate post-Soviet collapse were snuffed out by the dictator and his cronies, who clung to power using whatever means necessary – including, perhaps most notoriously, a 2011 massacre of striking workers calling for basic labour laws.

Which is when Blair stepped in. Not only did he participate in a regime propaganda video – claiming to listeners that Kazakhstan under Nazarbayev was ‘almost unique… in its cultural diversity and the way it brings different faiths together, and cultures together’ – but Blair began making claims such as Kazakhstan being the ‘only country to have given up nuclear weapons.’ (Ukraine also gave up their nuclear weapons in the early 1990s – a decision many Ukrainians now regret.)

But Blair didn’t stop there. In a letter to the autocrat, Blair suggested that Nazarbayev should argue that regime’s massacre, ‘tragic though [the events] were, should not obscure the enormous progress’ of his dictatorship. Blair then drafted parts of a speech for Nazarbayev, helping deflect from the massacre.

Meanwhile, Blair’s wife, Cherie, signed up with the regime for her own legal services, offering a charitable rate of just over £1,000 per hour to review ‘bilateral investment treaties,’ raking in hundreds of thousands of pounds in the process. The Kazakh regime also hired the London-based Portland Communications – a PR shop founded by a former Blair adviser Tim Allan. (Part of Portland’s strategy apparently involved stealthily editing Wikipedia entries of Nazarbayev’s opponents.)

Over and again, Blair and his network helped autocrats open doors in London. From Kuwait to China, the UAE to Vietnam, Blair apparently never found a despotic regime that he felt was too compromised to do business with. The former Prime Minister claims that the funds he brought in, including those from places like Kazakhstan, never went toward him directly, but instead fund his charities.

There’s one other, clear difference between the American and the British foreign lobbying sectors. While US-based foreign lobbyists must register and disclose their work, as well as their payments, to both American authorities and members of the American public, there are no comparable registration and disclosure requirements for their British counterparts. Whereas the US’s online Foreign Agents Registration Act database provides all of these details to anyone with computer access, there is nothing similar in the UK. All of which means we have to simply take Blair at his word when he says that he never pocketed any dictatorial money, let alone how much these contracts – $40 million reportedly in Kuwait, $27 million reportedly in Kazakhstan – were all actually worth.

Thanks to the former Labour leader, the world of foreign lobbying has become fully ensconced in London. That industry is booming, with no signs of stopping. Blair would no doubt prefer to leave this chapter of his career in the past. But it’s in Labour’s – and London’s – best interest to make sure his effort to return to the political fold fails. Should he be allowed to exert influence over the new government, Labour’s counter-kleptocracy policy will seem like rank hypocrisy. After all, if Labour is to join authoritarian regimes in seeking Blair’s advice, how are we to expect them to keep corrupt oligarchs out of the country?

Comments