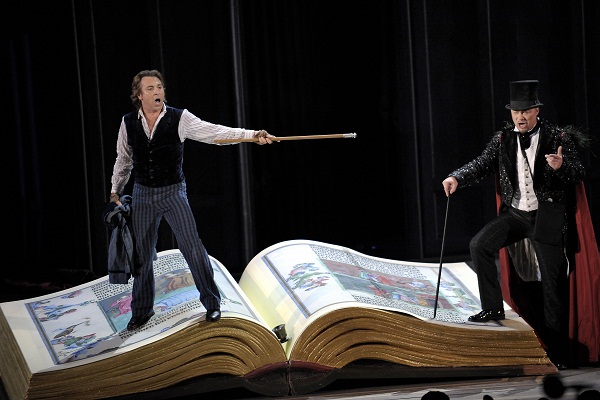

Faustus to Helen of Troy from Doctor Faustus, by Christopher Marlowe

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul, see where it flies:

Come Helen, come give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven be in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.

I will be Paris, and for love of thee,

Instead of Troy shall Wittenberg be sacked,

And I will combat with weak Menelaus,

And wear thy colours on my plumed crest.

Yea I will wound Achilles in the heel,

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

O thou art fairer than the evening air,

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars.

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

When he appeared to hapless Semele,

More lovely than the monarch of the sky

In wanton Arethusa’s azured arms,

And none but thou shalt be my paramour.

One of the things Doctor Faustus gets in return for selling his soul to the devil is an introduction to the most beautiful woman in history. What he says to her tells us more about him than it does about her. This is part of how Marlowe’s play works. Faustus’s character is created as we watch his reactions to the experiences he undergoes. As the play unfolds, we feel that we can make sense of Faustus as someone with a character, someone shaped by his own particular desires and limitations. All this creates a feeling that there is something behind what the script has Faustus say and do. He seems real.

What does this speech suggest about the man behind the mask? First, that Faustus is self-centred. Although his speech is prompted by Helen, he shows little real interest in her. He addresses her by name only twice. Both times he does so to demand a kiss from her (no thought of whether that’s something she’d like). The rest of his speech is given over to admiring her as someone might gush about an exquisite painting or a statue, and to making promises about what he will do for her. But all he can think to offer her is not to be unfaithful and to do a lot of fighting. Is this what she wants? The question is not asked. Her own desires seem unimportant to him.

Faustus is also hyperbolic. It’s all or nothing with him. Ilium’s towers (another name for Troy) aren’t just tall, they’re ‘topless’. And it’s not enough to admire Helen, he has to declare that ‘all is dross that is not Helena’.

Finally, Faustus is obsessed with classical literature. When he lays it on thick at the end he compares Helen to Semele and Arethusa, both of them characters from ancient Greek and Latin poetry. He also fantasises about re-enacting Homer’s Iliad. His sexual desire for Helen blurs with the intensity of his wish literally to become Paris (the Trojan prince who abducted Helen and provoked the Trojan War). As he imagines himself in this role lines beginning with ‘And…’ rush after each other in quick succession. His imagination is running away with itself, almost outstripping his ability to describe it.

Faustus is a renaissance scholar. His obsession is not unusual. Real life scholars like the Dutch priest Erasmus invested extraordinary hopes in the study of ancient literature. To the most ambitious, it was the key to returning the whole world to a lost golden age. Classical learning would allow them to rebuild the political and cultural life of Europe. They sacrificed time, wealth, and health to these hopes. And there was also the lure of worldly glory for themselves – especially as they built a culture across Europe which celebrated their own achievements.

Faustus’s destructive ambitious and diabolic pact are a mutation of this culture. Helen stands for all of these dreams and more. No wonder he finds her difficult to talk to and can’t get as much as a reply from her. The myth of Faust has fascinated people in Europe and beyond for over four hundred years just because he is a monstrous version of the men and women we often admire – people who are willing to sacrifice everything to do astonishing things, people who think that nothing is impossible. Faust was present at the moment people started to dream about living a life without limits. We may have given up on magic and alchemy, but whether we’re thinking about science, technology, or the economy, the idea that the future should be better is hard-wired into our way of life. Faust fascinates us because he’s a dark reflection of that faith and the lengths we’ll go to because of it.

Comments