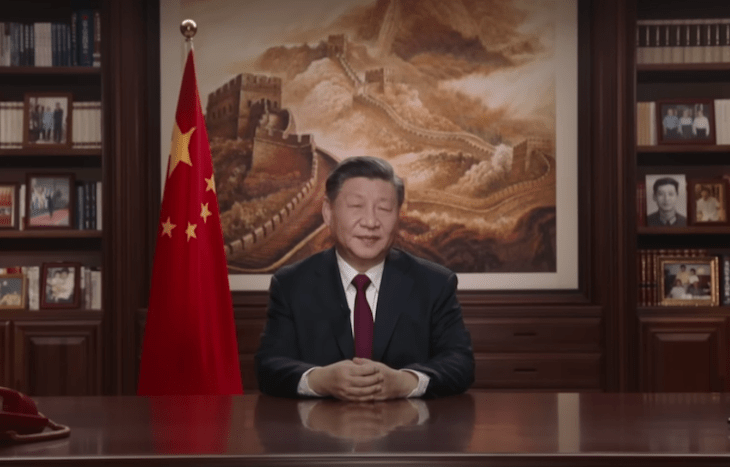

A few days ago, an email arrived from someone I know in China: my book The Great Sea had been spotted on the bookshelves of president Xi when he delivered his beginning of the year address to China and the world. China watchers were expending plenty of energy identifying the other books on his shelves, and came up with 62 titles. The great majority were by Chinese authors, including famous classics: the history of ancient China by Sima Qian and the Full Collection of Tang Poems, not to mention works by Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Admittedly there is a scattering of translations, including Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy and the complete works of Shakespeare, for whom Xi apparently has a particular fondness. What could a book by me, subtitled A Human History of the Mediterranean, say to the president of China?

China has returned once again to the sea

The clue lies in the fact that my Chinese correspondent had attended a seminar I gave at Nanjing University on seapower in 2019. This fascination with seapower in China is not unprecedented, but, in the long sweep of Chinese history, it is unusual.

In the twelfth century, the Song dynasty looked outwards, partly because the centre of power had been pushed southwards by enemies in the north; the capital was largely cut off from the land routes that had brought luxury goods across Eurasia along the so-called Silk Road. Until then, the main use of the compass, long known in China, had been to lay out buildings according to the rules of Feng Shui. Only now did its use at sea become obvious. When Song China was overwhelmed by the Mongol khan Kubilai in the thirteenth century ambitious overseas expeditions added conquest to trade, although attempts to conquer Japan (described by Marco Polo) ended in the destruction of the badly constructed Chinese fleet by the Kamikaze, or ‘divine wind’.

Chinese politicians as well as historians are particularly fascinated by the seven ‘Ming voyages’ at the start of the fifteenth century. The eunuch admiral Zheng He took charge of expeditions that reached as far as East Africa and even Mecca. In Chinese records, the size of the ships and armies sent into the Indian Ocean seems absolutely enormous, and it is questionable whether ships of that size would have been seaworthy. But even scaling these expeditions down, the reach of the Chinese at that time is very impressive. Debate rages about the purpose of the Ming voyages. But the best answer is that they were an attempt to show that, even if he did not rule every corner directly, the emperor of the ‘Middle Kingdom’ was master of the entire world.

After a long interval, China has returned once again to the sea: it is determined to demonstrate its economic and political power to the world. The Belt and Road initiative explicitly invokes the history of the Silk Roads, routes across and around Asia that particularly flourished in the early Middle Ages, and again in the era of Kubilai Khan. Although people tend to think of a continuous road across the Asian landmass, maritime links to western Asia, the ‘Silk Route of the Sea’, were always more important, whether the trade was conducted by the Chinese themselves or by Arabs, Malays, Tamils and other non-Chinese people.

Why, though, would Xi be interested in a book on the Mediterranean? As it happens, my subsequent book, a history of the oceans, is about to appear in Chinese translation as well, and is more obviously relevant to the Belt and Road initiative. There is a Chinese footprint in the Mediterranean – some years ago China began to invest in the port of Piraeus. But in China, Japan and Korea there is also a longstanding fascination with the history of the economic success of the West.

How did the European nations begin to generate prodigious economic growth, when during the Middle Ages China was arguably richer? This was the question that the Marxist historian of Chinese science, Joseph Needham, hoped to answer in his mammoth History of Science and Civilisation in China. How far back can one trace the great divergence between East and West?

None of this, of course, is evidence that president Xi has actually read my book. When I was being interviewed for admission to Cambridge I encountered a famous ancient historian in the college court and excitedly told him I had read his books. ‘There’s nothing in those books to harm a young mind like yours’, he said. I would say the same to all my readers, young and old.

Comments