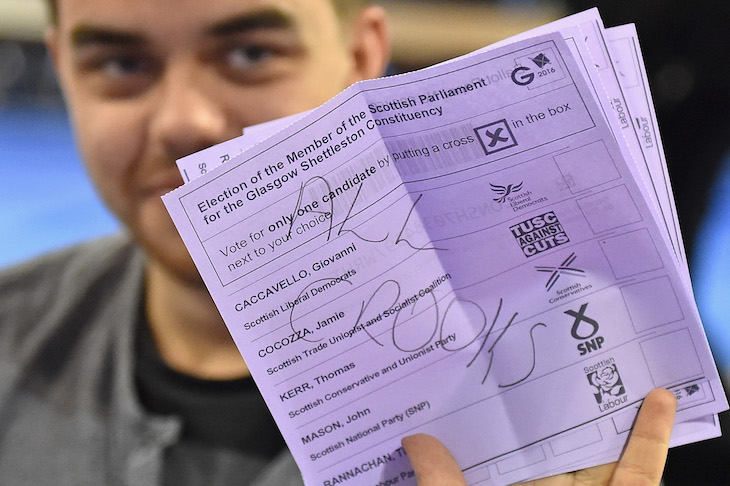

To choose is to endorse. But this is an election in which, for myriad reasons, all the options are deplorable. To choose one of them, even on a least-bad basis, feels like a kind of capitulation. So I will vote tomorrow but I shall, for the first time, spoil my ballot. None of the Above has my vote.

I want no part of this election and desire no share, however tiny, of the responsibility that comes with endorsing any of the candidates representing the major parties. To choose is to sanction and, in this election, that’s intolerable and impossible.

So last night’s YouGov MRP number-crunching was oddly cheering. For it raised the possibility, still faint perhaps but alive nonetheless, that this really could be an election without winners. That is the only result the parties merit; the only conscionable outcome. The tightening of a race no-one deserves to win felt like the first bit of happy news we’ve received in some time.

I still suspect Boris Johnson will be returned to Downing Street but this campaign has confirmed his limitations and offered a preview of the government he might lead, given the opportunity. A mendacious government too full of itself by far. A government lacking empathy and understanding. A government that cannot be trusted. A government of spivs and phoneys, too, not to mention one with Dominic Raab and Priti Patel occupying two of the great offices of state.

We are asked to believe that a Tory party that has divested itself – purged is the more appropriate term – of much of its moderate wing will somehow actually be a more moderate, decent, liberal Conservative government than would have been the case had the moderates been part of it. Come off it. I always thought Eddie Mair’s famous question to Boris Johnson – ‘You’re a nasty piece of work, aren’t you?’ – was unfair; this election has helped answer it, however, in ways that are not flattering to the prime minister.

The Tory prospectus in this election has been built on a number of whopping untruths but none has been greater than the suggestion that a vote for Johnson – a candidate who has grown smaller as the campaign has grown longer – will ‘get Brexit done’ in short order. Promises will have to be broken to avoid breaking any number of other things. Talks with the EU on the future relationship between the UK and Brussels are not likely to be concluded by the end of next year; insisting they must be, imposing a deadline on those talks, both weakens the British negotiating position and increase the possibility of a cliff-edge departure of the kind that’s worst for British business. The withdrawal agreement – a no-score draw at best now reimagined as a 4-0 victory for Britain by feverish Tories – is the easy, less important, part.

Even there, however, on the subject of what is notionally his great triumph Johnson has preferred to peddle nonsense. There will be a de facto border, if one of an unusual sort, in the Irish Sea and no amount of pretending black is white can make it so. That doubling-down on untruths, however, is consistent with what we know of Johnsonism. I said it, therefore it must be so, he suggests, albeit this is sometimes tempered with a wink to let you know this too is bollocks but does that really matter in the grander scheme of things in this day and age?

Well, yes, actually it does. Without wishing to be too priggish about these matters, it is important the prime minister has some observable relationship with veracity and some appreciation why that matters. Politics is built upon norms and precedent; it is a game played according to well-established rules. Break those, undermine that hitherto accepted contract, and you inject a certain poisonous cynicism into the political system that will debilitate it for years to come.

At some point, a fresh start will be required. That requires an opposition party of modest respectability. British politics can cope, just about, with one of the two largest parties misbehaving; it struggles when both do. The Labour party has spent the past three years indulging itself to an unconscionable degree. The problem is not just Jeremy Corbyn, though he is of course a problem too, but rather Corbynism. That virus will remain in the Labour bloodstream long after the great gourd-grower returns to his allotment.

And it really is something new. Labour has not hitherto been led by people who think, as Andrew Murray, one of Corbyn’s closest advisors does, that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a ‘great leap backwards’. That is both a qualitative and a moral difference from Labour parties of the past that, however much you might disagree with some of their policy choices, were at least recognisably part of the mainstream traditions of British politics. Corbynism is as great a rupture with those traditions as a Labour party led by George Galloway would be.

In such circumstances, concerns about nationalising the trains seem trivially beside the point. It is much more telling that Corbyn lavishes praise on the Chavez-Maduro regime in Venezuela and that John McDonnell tells us that the Castro regime in Cuba would have no greater friend than a Labour-led United Kingdom. This is what they believe and we should give them the credit of taking what they believe seriously.

And then there is the question of the Jews. Whatever Corbyn’s own views, there is simply no avoiding the fact he has travelled with, saluted, and otherwise encouraged copper-bottomed anti-Semites. The record is as clear as it is deplorable. There are anti-Semites who will vote for every party in this election, but only the Labour leadership gives them tacit license. Every person thinking of a Labour endorsement has had to grapple with this before accepting it. All the weary ‘buts’ and ‘yets’ cannot avoid the reality that these endorsements ask the British people to vote for something morally obscene. Britain’s Jews must suck-it-up for there are more important things at stake than them. You make that choice if you wish to; I refuse it.

Voting for the Conservatives on the grounds they are less bad than Labour does nothing to make this iteration of the Conservative party an acceptable one any more than voting Labour because they are less indecent than the Tories makes them anything other than indecent themselves. Sometimes it is important not to settle for second-worst.

Theoretically this ought to have been a liberal moment. Alas it proved to be a Jo Swinson one instead. ‘Revoke Article 50’ must have seemed a clever wheeze once upon a time and a means of putting clear Remain water between the Liberal Democrats and Labour. Instead, it was a thunderous admission of absurdity that rendered the Lib Dems as unserious as everyone else. This. Is. Not. A. Plan. You can’t just ‘cancel’ such things. Swinson, indeed, has seemed determined to scuttle the Lib Dem ship single-handed. It has been impossible to avoid wondering how the Lib Dems would have fared if they’d been led by Paddy Ashdown, Charlie Kennedy or even the 2010 version of Nick Clegg. None of them, I fancy, would have struggled to answer the question ‘What is a woman?’.

In Scotland, of course, there is another option available. Alas, voting SNP is equally impossible since it is, aside from anything else, a proxy vote for a Jeremy Corbyn to become Prime Minister. Nicola Sturgeon readily concedes he is not fit for Downing Street yet she is prepared to put him there anyway. That alone is sufficient to disqualify her.

There has been something grim, too, about witnessing the seemingly endless parade of southern liberals admiring Sturgeon while conveniently forgetting her chief aim in life. This reached a moment of, I presume, unintentional hilarity when ‘Best for Britain’, which was founded by Gina Miller, recommended voting for SNP candidates in a number of marginal Scottish constituencies. Independence is a perfectly respectable cause; it’s not obvious that the break-up of Britain is best for Britain. If there’s a second Scottish independence referendum – though it’s not likely to happen next year and the SNP have any number of difficult problems and unanswered questions of their own – I’d expect Yes to win.

All in all, then, this has been a thoroughly depressing election in which the only cheering moment has been the emergence of the possibility no-one might win it. But if to choose is to endorse then refusing to choose is a choice too and one that seems worthier than any of the alternatives. Let the chips fall where they may; there is no need to stain yourself by voting for any of these parties. Let it be on other peoples’ heads.

We may not get anything better than this; we may still demand something marginally better. Vote None of the Above.

Comments