Jane Austen: Rise of a Genius began by saying that ‘getting into her mind isn’t easy’ – something you’d never have guessed from the rest of the episode, where both the narrator and the talking heads were able to tell us exactly what Austen was thinking and feeling at any given time.

Like many Austen biographies, this one laments her sister Cassandra’s decision to burn most of her letters, but then takes full advantage of how little we consequently know about her to portray (or possibly make up) a woman whose attitudes are spookily close to its own. In a previous era, this might have meant presenting Austen as a gentle and contentedly domestic aunt. Now of course it means that ‘at a time when women were supposed to know their place, Austen ripped up the rulebook’. Equipped with its privileged access to her mind, Monday’s programme further explained that after ‘feeling a lack of autonomy’, she decided ‘to pursue the route of being an independent woman’.

Some irksome pedants (me, for instance) might suggest that in order to make Austen a proper feminist heroine, the programme has to contort even the little we know to fit a preordained narrative. Either that, or ignore it completely. Need Austen to be a pioneering female voice in the male world of novel-writing? Simply erase all the other women – Maria Edgeworth, Fanny Burney, Ann Radcliffe etc. – who were already successful novelists.

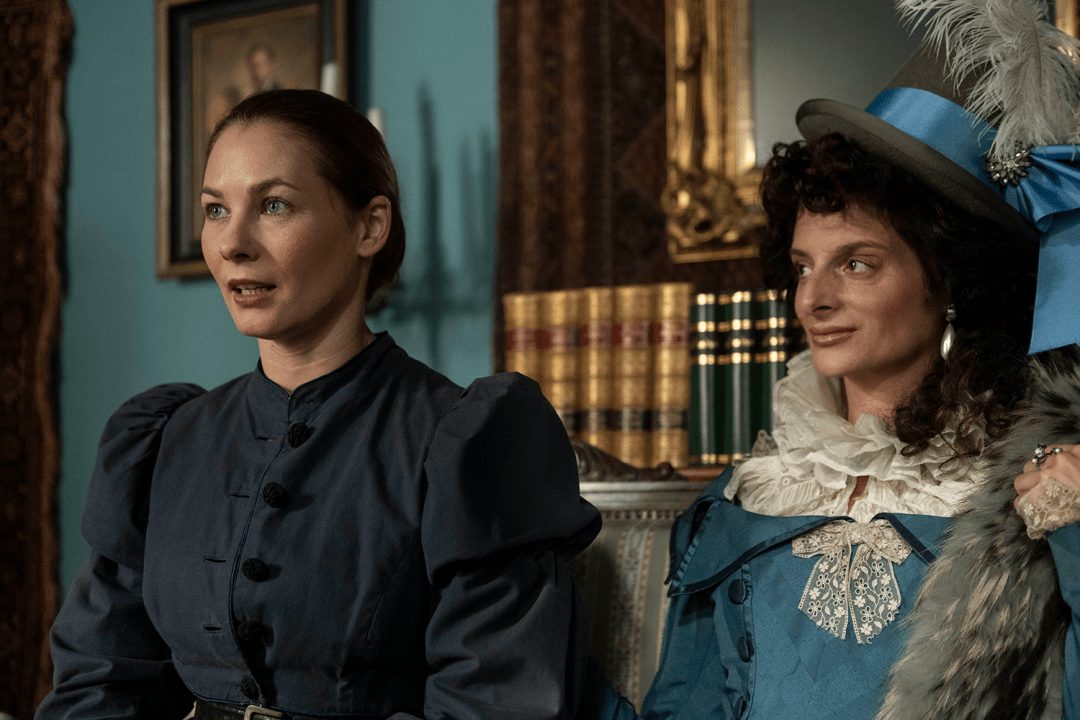

Occasionally, too, we had the strange sight of Austen biographers contributing to accounts different from the ones in their own biographies. In 2013’s The Real Jane Austen, Paula Byrne describes cousin Eliza arriving at the Austens’ Steventon rectory in 1786 and visiting periodically after that, including for several months in 1792-3. Here, it suited the programme’s purposes to have the racy Eliza suddenly showing up at Steventon for the first time in 1794 to become Austen’s ‘fabulous role model’ – so this, with Byrne’s co-operation, is what we now heard.

Not long afterwards, Eliza’s French husband was guillotined during the Reign of Terror and, in the same book, Byrne noted ‘there is no way of knowing how the execution affected Austen’. But here, according to a fellow contributor, ‘it caused her much fear which seeped into her subconscious’: a ‘fact’ confirmed when in one of the show’s wordless dramatic reconstructions we watched Austen sitting bolt upright in bed following a nightmare.

Inevitably, there’s also the liberal use of the word ‘modern’ – which on television is about the highest compliment you can pay to a writer from the past, proving as it supposedly does that the writer in question isn’t so irrelevant as to give us characters who aren’t just like ourselves. Again, those irksome pedants might argue that the point of fiction is to find out about other people. But the programme stuck fast to the approved idea that the point is to find out about us. (After all, what finer subject could there be?)

For a while now, BBC1’s Sunday telly has been returning to its cosy, family-friendly roots. This week’s line-up therefore brought us Countryfile, the Chelsea Flower Show, Walking with Dinosaurs and Antiques Roadshow. And that was before Death Valley, a new police drama that’s a lot happier than Happy Valley and apparently aimed at people who consider Beyond Paradise a bit too gritty.

Set in Wales, the show leaves nothing to chance, combining a comfy whodunnit with any number of lovably eccentric locals, an old bloke with an impeccably curmudgeonly exterior, lashings of broad comedy – and a total indifference to realism.

Leading the lovables is DS Janie Mallowan (Gwyneth Keyworth), whose ditziness requires her to keep making tactless remarks while bumping into things. Her first case concerned an evil property developer (is there any other kind?) who’d seemingly committed suicide – i.e. been murdered. Knocking on his neighbours’ doors in a quest for witnesses, she had a sort of non-erotic meet-cute with John Chapel (a scenery-chewing Timothy Spall), whom she’d long loved as the star of her favourite TV detective series and whose somehow unsuspected presence in the village sent her ditziness into overdrive.

For his part, Chapel was determinedly unimpressed. But being an actor who prides himself on his close-observation skills, he couldn’t resist wanting to crack the case. The non-erotic romcom then continued as the two alternated between shouting at and reluctantly liking each other. But could she pierce his grumpiness, and could they solve the murder? The answer to both questions was yes – as I imagine it will be to the same questions in every future episode.

Faced with this stuff, the obvious choice is to either shake a stern-minded head at the unsubtle ludicrousness of it all, or to pour yourself another glass of wine and enjoy the unsubtle ludicrousness of it all. Personally, I advise option two.

Comments