Whenever I tell people I used to be a maths teacher the most common response is: ‘I absolutely hated maths at school.’ It is an age-old tale, to loathe maths lessons (or indeed your maths teacher). So, what better way to make children loathe maths even more than to make it compulsory until the age of 18?

Rishi Sunak’s plan, announced at the start of the year, aims to address innumeracy and better prepare pupils for the workplace. There are many reasons why, on the surface, it seems a sensible approach – not least because the UK is one of the few countries in the world that does not require children to study maths in some form up to the age of 18.

It is unreasonable to prevent children from learning what they love

Some critics have argued that the plan shows a government which is out of touch, unaware of the recruitment crisis plaguing state schools. After all, how can we expect the further provision of two years of maths when maths teacher recruitment targets have been missed every year for more than a decade? Currently around 45 per cent of UK secondary schools depend on non-specialists to teach the subject.

During my time as a teacher in an inner London school, class sizes from Year 7 to A-level all ballooned – placing great strain on an already stretched workforce. The recruitment crisis is having a big impact on the quality of maths teaching across the UK. What struck me most when I interviewed for teaching positions was the number of applicants who just couldn’t teach. Many could not hold a room or engage a class, let alone break down a concept into its simple components or introduce a topic in an interesting context with energy and confidence. Bad maths teaching is rife, and this is not only due to the increase in non-specialist teachers.

It is a common misconception that bright Oxbridge graduates with engineering degrees make good maths teachers. Some of the best maths lessons I saw were delivered by people with degrees in art history or English. What is truly lacking in the profession is the understanding that being an effective maths teacher requires not just high-level subject knowledge, but creativity.

Those in favour of Sunak’s reforms quite rightly say that numeracy skills are a necessity in the working world. But this policy is reactive rather than proactive: education policy focuses too much on patching over problems at a later stage – at GCSE or A-level – rather than considering improvements to the early stages of a child’s educational life.

I would see an enormous range of numeracy skills from children starting secondary school, indicating varying levels of effective teaching at primary level. Schools for children in their early years need to be better equipped and staffed to provide this. But parents also have a big role to play, whether by asking their child to tell them which is the cheaper bag of pasta in a supermarket or reading aloud a worded maths problem in their homework.

The maths-to-18 policy is also symbolic of a wider cultural issue that has intensified in the past decade. The government’s preference for STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) over the arts and humanities is leading to the loss of interest in – and access to – creative subjects in state schools.

There has been a marked decline in the choice that pupils have, due to timetable blocking and the disappearance of entire departments. Nearly 20 years ago, state-school friends of mine took art alongside textiles and music. Now, that same school no longer has a Design and Technology department. In its place is a tiny art ‘faculty’ with fewer than half the members of staff it once had. Pre-GCSE pupils are taught art for around one to two hours per fortnight, and their chances of learning how to design garments or work with wood and metal are non-existent. This form of education cannot be an effective provision for any community of individuals with aspirations to be creative.

At A-level, entries for business studies and computing have seen the largest proportional increase in recent years, while those for subjects such as drama, music and design fell by 28 per cent between 2014 and 2019. Of course, an uptake in computing needn’t be a bad sign in a technology-driven world, but this cannot be the only reason for the sad decline of the arts. We still need artists and designers, playwrights and musicians, actors and journalists. These professions enrich our lives and are vital for economic prosperity.

In 2021, the then education secretary, Gavin Williamson, praised the influx of engineering and science undergraduates in universities as a positive sign that students were starting to ‘pivot away from dead-end courses that leave young people with nothing but debt’. His comment shows it has become commonplace to judge the success of a qualification by the salaries it leads to, rather than the joy it gives us. It is sad to think of creative subjects as financially defunct and therefore not worth studying.

Those in favour of the maths-to-18 policy believe it will bridge the gap between privileged and underprivileged children. But state schools are under such pressure to attain good Progress 8 performance scores – a measure of the results of mostly academic subjects – that non-academic children are taken out of their much-loved music lessons, or even told they cannot take a creative GCSE, in order to be taught extra maths, often with negligible outcomes.

We still need artists and designers, playwrights and musicians, actors and journalists

Surely it is not a sign of privilege to have limited choice. Of course, there should be a minimum set of disciplines that are compulsory for pupils to learn, but it is unreasonable to prevent children from learning what they love. Denying a child three hours of drama a week with extra maths in its place could raise a school’s Progress 8 score but inevitably undermines the joy of learning.

Over the years I have met children who would be utterly vile in their maths lessons by disrupting the class and refusing to work, resulting in them being removed. Often, I would see the same child sitting calmly in an art lesson, focused on the beautiful design they’d printed from a linocut, or beaming from the applause they’d received after playing bass in the summer concert. We can all relate to being put off by things we are forced to do, but also to the delight that comes from being absorbed in things we love. For some children this is maths and science. But a significant proportion of creative children in the state sector are being denied the option to study a variety of creative subjects or are being convinced to go down the STEM route simply because it is more lucrative.

Many excellent schools across the country understand that a rich curriculum is a collection of interconnecting disciplines, where STEM is not separated from the arts, and where mathematical language can be applied to multiple contexts. Children can learn to read graphs in geography as much as in computing, or to interpret statistics in history as much as in biology. Young people starting out in the world of work will find that skills they learned in school begin to fall into place because they have a practical application.

Raising literacy and numeracy standards across the UK is not going to happen by reducing the curriculum in state schools to core subjects only. What is needed is a reversal of the attitude that arts and humanities limit a person’s job opportunities and their earning potential – and a belief in a child’s choice to learn about things that they love.

Can you answer these O-level maths questions?

From June 1974 O-level Question Paper 450

Question 1

In a certain village 3/16 of the inhabitants are over 60 years old, 1/8 are between 15 and 30 years old and 1/4 are under 15.

The remaining 35 people are between 30 and 60 years old. If there are 7 men in the village who are over 60, find the number of women over 60.

Question 2

Given that the remainder is 12 when the expression ax3 + 3x2 – 11x – 6 is divided by x + 2, calculate the value of a.

Using this value of a, find out whether 2x + 1 is, or is not, a factor of the expression.

Question 3

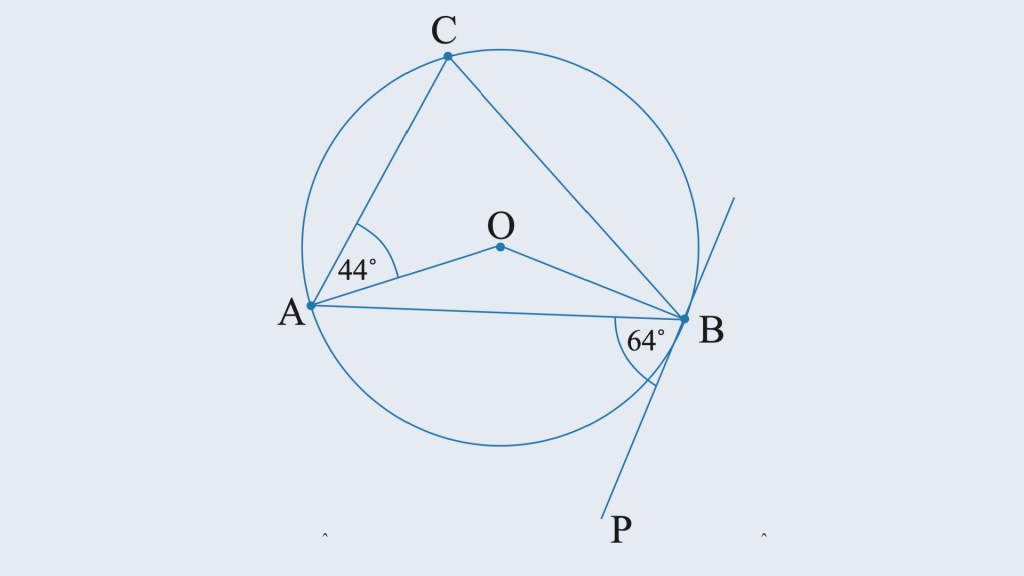

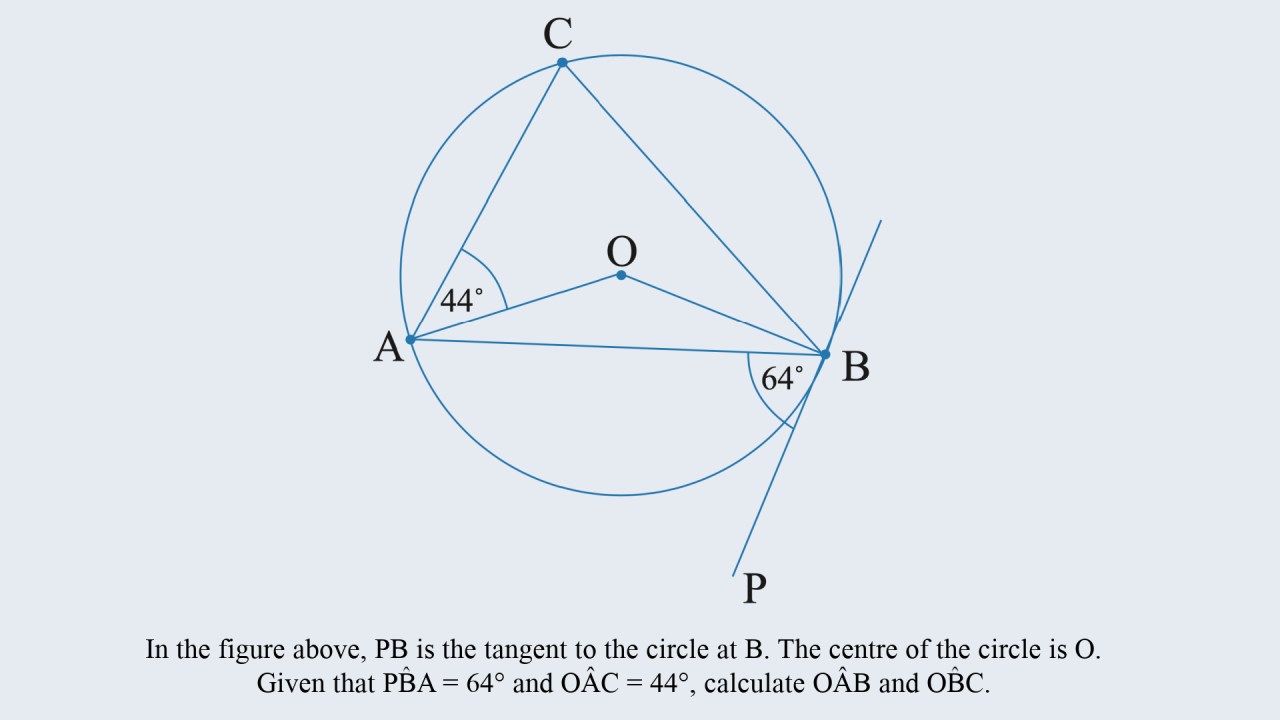

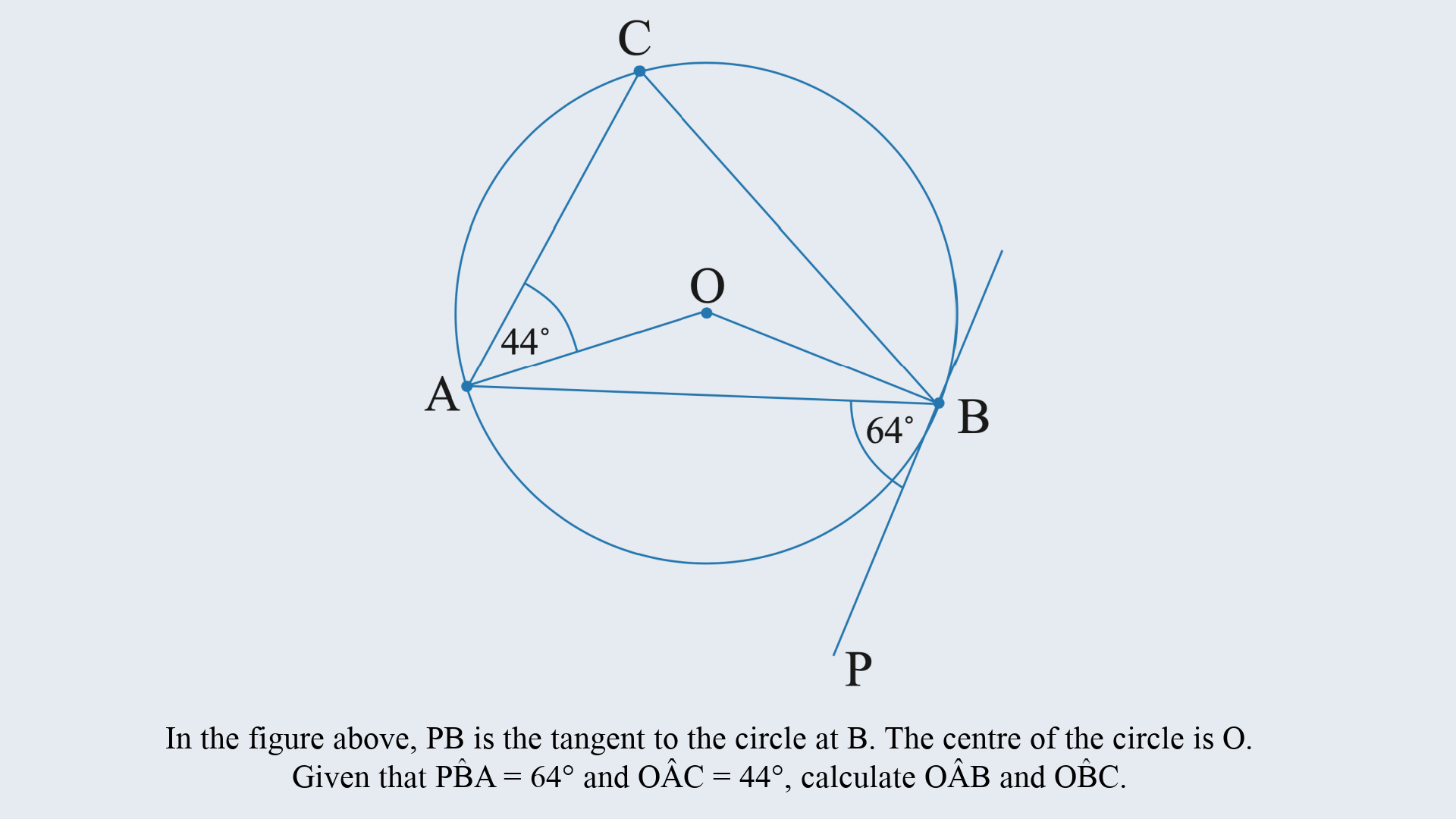

In the figure below, PB is the tangent to the circle at B.

The centre of the circle is O. Given that PB̂A = 64° and OÂC = 44°, calculate OÂB and OB̂C.

Answers: 1) 8 2) a=2. Yes, 2x + 1, is a factor of the expression ax3+ 3x2 – 11x – 6 3) OÂB = 26°, OB̂C = 20°

Comments