Medieval women – they were ‘just like us’. Except that they weren’t. Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife is the first popular book by the academic and New Generation thinker Hetta Howes. It is a history of medieval women in relation to four celebrated figures – Marie de France (poet), Julian of Norwich (mystic), Christine de Pizan (widow) and Margery Kempe (wife) – whose lives have been retold recently in excellent studies by Anthony Bale, Marion Turner and Janina Ramirez. Howes’s book is highly readable and informative, placing the works of this quartet within a broad range of cultural documents – treatises, guidebooks, wills, court records and folklore. There are some great details, such as the theological debate about the Virgin Mary’s orgasm.

Howes limits her scope, however, by looking too narrowly for ‘relatability’ in the medieval lives she surveys, where this is determined by the boundaries of her own experience. In her introduction, she claims that over the past two years she has ‘felt closer to these women than ever’. I was curious: did she have a vision of the universe appearing like a hazelnut in the palm of her hand, like Julian? Did she renounce sex and take to the public square weeping, like Margery? Did she write an allegorical takedown of her detractors, like Christine? Or did she compose a ground-breaking translation of Aesop’s Fables, like Marie? No: she planned a wedding and became pregnant.

I congratulate Howes on these life events, but I struggle to see how such experiences shed any light on medieval lives, given that the paraphernalia of contemporary marriage – from the white dress to canapés to the typically non-Latinate service – would have been entirely alien to medieval people. There is no such thing as a transhistorical quintessentially ‘female’ experience – but if there were, it definitely wouldn’t be wedding-planning.

What is more, from the written evidence they have left us, these four women didn’t seem to care that much about marriage or children. Take Margery Kempe. Yes, she did have 14 children, and, yes, she describes the excruciating pain of childbirth. But the only time in her autobiography that any of her children feature is when one of her daughters tries to prevent her from going to Germany – which Margery is righteously indignant about. By focusing on Kempe’s marriage and the children, Howes manages to pull out the parts of life which the woman herself seems least interested in.

Howes describes Margery’s mystical transformation as ‘an illness that sounds remarkably like postnatal depression’. Attempting to diagnose Kempe’s malady has been a tired vein in academic criticism for decades, but I thought we had moved beyond that. Howes flattens the diversity and strangeness of medieval lives into a recognisable package when she re-labels them uncritically in this way – so Christine de Pizan becomes ‘the definition of a hustler’.

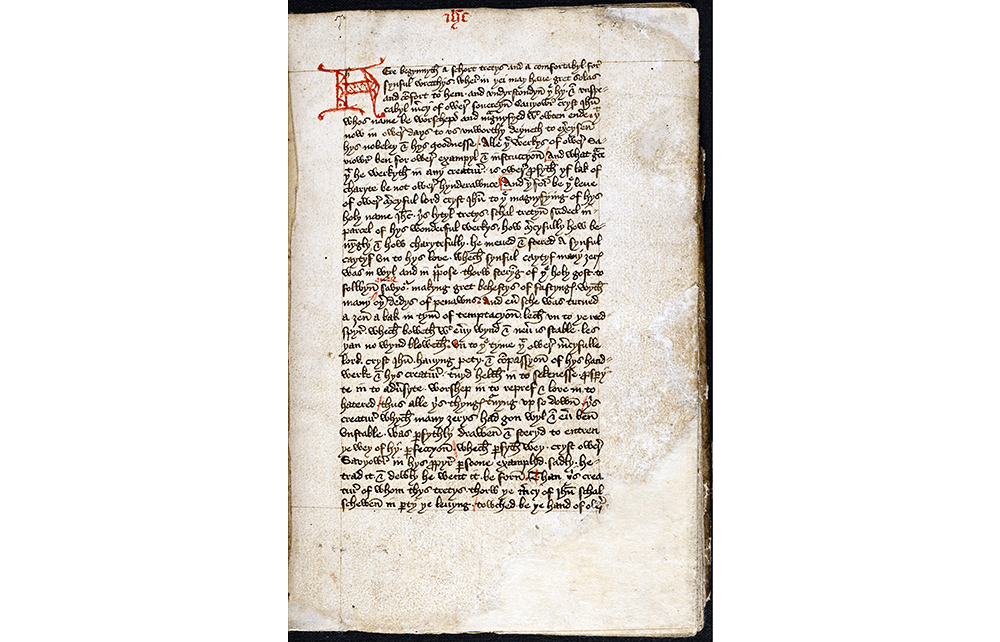

Howes often excuses her own limitations as ‘silences’ in the archives. For example: ‘Gay women existed in the Middle Ages, but with records dominated by the heteronormative, we are left to imagine their stories.’ In fact there is a well-established creative and academic tradition which presents Kempe and Julian of Norwich as queer figures. When Margery met Julian, she described the warmth of their encounter in vivid terms as ‘holy dalliance’. ‘Dalliance’ is a Middle English word which can be translated as ‘conversation’, but also means ‘flirtation’ and even ‘sexual union’. The women’s intimate encounter is just one example of many scenarios Howes fails to discuss that would have provided much more material with which to ‘imagine’ lesbian histories. Instead, she rehashes her chosen biographies without reference to those interpretations.

Similarly, discussing sex work, she writes: ‘We don’t know how women felt about their work in these brothels’. But one of the most carefully examined medieval court records of the 14th century contains the voice of Eleanor Rykener, who also went by the name of John and worked as a seamstress, bartender and sex worker. In her discussion of the Latin word virago, which was glossed over in medieval England as ‘manliche womman’ (literally, man-like woman), Howes gives an interpretation which closes the door on queer readings. Viewing viragos, as she does, as ‘warrior-women’ superimposes a Marvel-verse vision of femininity on to gender non-conforming figures such as Joan of Arc. I could go on.

Howes begins her book with a critique of the essentialism of medieval misogyny. But she would have benefitted from applying that critique to her own uninterrogated and essentialist assumptions about gender. She writes that ‘we are now incorporating’ medieval texts into ‘our own 21st-century approach’. I dispute that claim. Her approach belongs in the 20th century.

Comments