Our House of Lords is so fat it’s the butt of ridicule. More than eight times as many members ‘sit’ in our second chamber as in the Senate of the United States. True, some Lords in former lives did great or good deeds. Not all in our upper house are mere political paymasters or hoary ex-vote-winners. But we have too many of every sort in there: far too many.

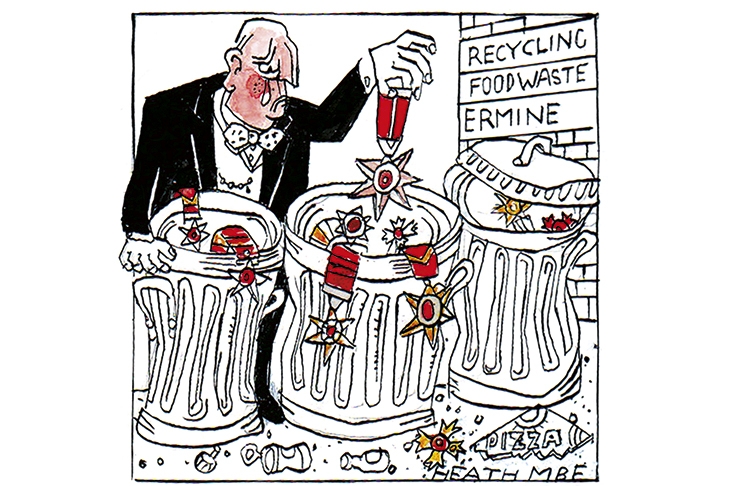

One whole incestuous layer could be dug straight out of the UK honours system: out from the Lords, and out also from below it. Nobody from our media should carry a title. And none needs, either, to wear a gong. Not broadcasters, not journos, not editors, not their managers — and certainly not their owners.

Take the Daily Express, perhaps Fleet Street’s most uncritical cheerleader for Margaret Thatcher’s final government. The paper’s editor Nick Lloyd (a fine tabloid veteran) was rewarded by a knight bachelorhood of the realm in Mrs Thatcher’s resignation honours. The chairman of that same newspaper group — Baron Stevens of Ludgate — got his life-peerage earlier still, in the very year of Mrs Thatcher’s third general election victory. Some years later a formidable conservative and controversialist, the owner of the Daily Telegraph and The Spectator, changed citizenship to be made a Lord. No comment.

Journalists report and editorialise, but do not govern; we judge a lot, but we are not the judiciary

This is about journalists’ proper place in society. We journos report and we editorialise, but we do not govern. We are not in the legislature (or ought not to be). We judge a lot, but we are not the judiciary. Journalists are and need to remain — using that self-regarding Americanism — this country’s Fourth Estate. Outsiders with our own look at society, at politics, the economy. Uninfluenced, uninfluenceable. Separate. Uncorrupted by the chance of favour, let alone an ‘honour’. Incorruptible not merely in fact, but in the perception of us by others. Our antagonists may be biased, motivated or hostile to what we say, write or publish. But let’s free them from impugning this particular motive.

It’s not that we editors or writers act in hope of making Her Ladyships out of our wives. But that’s among what we’ll be suspected of when we take ermine, or when Her Majesty’s sword touches our shoulder. We may tell ourselves that the honour comes from the crown, but a cub reporter knows the list is drawn up by politicians to exercise power of patronage. It’s a power to which no journalist or media figure should be susceptible.

Take two of today’s great newspaper columnists: Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins. Superb former editors, of the Daily Telegraph and The Times respectively. Both also edited the Evening Standard. Both now Sirs, ‘for services to journalism’. One of them said he would not use the title, but does. And the question for both is: was it right or wrong for them to accept the honour, when they are known for their newspaper editing and are still professionally swaying political opinion as newspaper columnists?

Or take two writing lords: Charles Moore and Danny Finkelstein. I regard them as two of today’s finest political columnists, and not just because I agree so often with them. The quality, sensitivity and rigour of their thought are models for any of us. Moore has been (twice) a broadsheet newspaper editor and took the helm of The Spectator at a time when its future was in jeopardy. Each of these journalist Lords broadly supports today’s government, one of them takes Boris’s whip. Lord Moore was a persuasive and powerful newspaper advocate to get Brexit done. Lord Finkelstein mildly ditto. Fair enough as newspaper commoners. I cheered. But I don’t believe Lord Moore, or at an earlier time Lord Finkelstein, should have accepted their offers to sit in the nation’s upper legislative chamber.

I recall meeting Robin Day one evening on Andrew Neil’s crowded balcony in Onslow Gardens. Robin, a mighty friend, had just become Sir Robin. ‘You ought not have been offered it,’ I told him. ‘And when offered, as our tribune you might have courteously, quietly turned it away’ (as I later did). Uproar! Unlike our host that evening, or me — both Roundheads — Robin was a true Cavalier, brilliantly insecure and passionately patriotic. The row escalated over canapés. Being knighted, Robin bellowed, was the proudest insignia and recognition of his life.

There’s no question that Robin meant and felt it. An audience with the Queen signified — deeply, sincerely and patriotically — so much to him. He was the Grand Inquisitor of TV interviewing. He royally merited his knighthood. As did that other stupendous TV newsman, Alastair Burnet. But both of them could have turned down the award when offered it, to underline the separation between journalism and politicians.

When Bill Deedes was readying to step down from editing the Daily Telegraph in January, 1986, I told him (forgive my single inconsistency here) he must go into the Lords. ‘Certainly not!’ came Bill’s scoffing reply. ‘I don’t want to spend my day with all those old bores.’ It took the prime minister (and her husband) to twist his arm.

Lord Deedes went on after editing to do splendid public service — notably in his campaign against landmines. That really would have merited his honour. But when he received a knighthood in 1999 it was in part for ‘services to journalism’. The only reward for ‘service to journalism’ any newspaperman or broadcaster should covet is to be trusted, read and heard by the reader and the audience. No gift whatever needs to come from government.

Comments