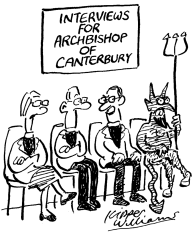

On 21 July 1828, the urbane aristocrat Charles Manners-Sutton, 89th Archbishop of Canterbury, died. Just two and a half weeks later, on 8 August, the mild-mannered linguistic scholar William Howley was elected as his successor. The efficiency of this process is in marked contrast to the current search to find the next successor to Manners-Sutton and Howley. Justin Welby announced he was vacating the throne of St Augustine on 12 November last year; it took until 28 May even to assemble the committee who will discuss the names of his potential successor. It will be a miracle if we know the name of the new Primate of All England by the autumn.

That committee – the Crown Nominations Commission (CNC) for Canterbury – has been beset by incompetence, factionalism and bureaucracy from even its theoretical inception. The election of the three CNC members who represent the diocese of Canterbury itself took four attempts, with accusations of irregularities and malice flying around, while the process for nominating the five CNC representatives from the global Anglican Communion was so opaque that no one really understands how they were picked at all.

When confronted in an interview about the lack of efficiency, the CNC’s chairman, the former MI5 chief Lord Evans, stated that ‘it’s a more inclusive and consultative process’, which are adjectives popular with officials not because they reflect the reality of things but because they are almost impossible to criticise. Everyone wants things to be more inclusive and consultative, don’t they? Well, there are merits to both those values, especially in their proper places – a new parking scheme at an NHS dental practice, for instance. They are not, however, qualities that I think are essential to the selection of the Church’s most senior cleric.

Actually, as much as the speedy appointment of Archbishop Manners-Sutton’s successor seems preferable to that of Archbishop Welby’s, I don’t believe efficiency is an essential quality to the process either. The only adjective I would want is ‘holy’. Can this be called a holy process? Even the most generously minded person would struggle to give it that epithet. While discernment might well be crucial in arriving at what the will of God might be, there is nothing innately holy in long-winded consultation and bloviating statements of intent. The process smells of HR orthodoxy.

Therein lies a more worrying issue: that those involved in the process don’t appear to want it to be holy. Lord Evans has taken pride in the fact that it mirrors the values of the secular world. He has made clear that he thinks the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion ought to be prominent in shaping the longlist and that the process – which other members of the Church have referred to as ‘an omnishambles’ – is a good thing in and of itself, even describing it as ‘joyful’. Of course, Evans isn’t personally to blame. He admits that he is ‘very far from being a church historian’ and that he is ambivalent about the Church’s constitutional status. He was appointed to the role by the Prime Minister, and he is only following the thread of the labyrinthine process set out by the Church’s policy-makers and waved through by Synod under Welby. The chair of the CNC, like the rest of its makeup, is merely a cipher for the managerial caste who dominate our institutions to exert their influence and shape the culture.

Just when a change in culture is needed, the same culture has shaped the process for selecting its leader

In many ways this should not come as a surprise. One gets very used to bureaucratic statements coming from the central Church and equally accustomed to ignoring them. Yet the agonising CNC process shows that one of the Church of England’s favourite phrases – ‘lessons learned’ – is nonsense. If the official takeaway from the disastrous Welby years is that we need more committees, more LinkedIn-style careerism and more empty management-speak, then the Church’s administrative elite have proved that they aren’t capable of learning lessons at all.

Perhaps most worryingly, the CNC process also saddles whoever gets the job with a woeful pedigree: how can we expect them to be, as the Prayer Book service for a Bishop’s Consecration encourages, ‘wholesome examples’ or to ‘feed their flock’ when the system that chose them has different priorities? Put another way, having been recruited by a process which is enslaved to managerialism, how can the new Archbishop free the Church of England from its Babylonian captivity to the same? At the exact moment when a drastic change in culture is needed, the same culture seems to have shaped the entire process for selecting its leader.

This issue goes beyond churchmanship or theological disputes; it is about existential questions of the vision of the Church. Does its hope for its future lie in the promises of Christ and the power of the Holy Ghost or in the procedures and policies, the consultations and the tinkering cymbals of management culture?

It might seem credulously optimistic with our current crop of leaders, but it remains my hope and prayer that we will get a good Archbishop. I do believe in miracles. I have to. Yet even if that does come true, all this still represents a deep problem at the heart of the Church. The person who ends up as Archbishop of Canterbury may well prove to be inspiring and holy, capable of profound preaching and acts that show grace – indeed they may yet prove to be the person who calls the English nation back to the service of God. But they won’t have been selected because of this. They will have been selected because they tick the boxes of a committee.

The Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie’s book Twelve Churches: An Unlikely History of the Buildings that made Christianity is out on 28 August.

Comments