In an effort to hasten the Assisted Dying/Suicide Bill on to the statute books, Esther Rantzen and Lord Falconer have offered a novel interpretation of the role of the House of Lords. Falconer suggested that the Lords must ‘uphold’ what ‘the Commons have decided to go ahead with’. Meanwhile, Rantzen said of Parliament’s upper chamber: ‘Their job is to scrutinise, to ask questions, but not to oppose.’ Someone like Rantzen may be forgiven for playing so loose with conventions, but a former Lord Chancellor may not.

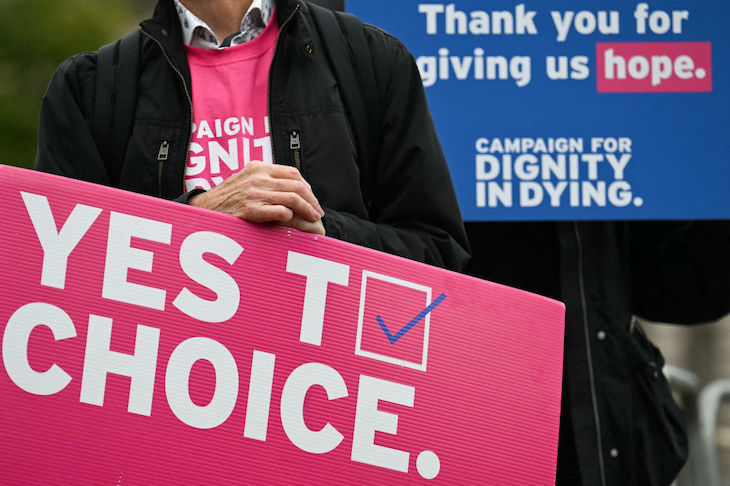

Labour’s manifesto made no reference to assisted suicide nor assisted dying

The reality is that both the House of Commons and the House of Lords play an equal role in the passing of legislation, except when it comes to matters of financial privilege. For legislation to become law, it must be approved by both Houses; where there is disagreement on the detail, there is negotiation through ‘ping pong’ until agreement is reached or the Bill falls. This encourages both Houses to compromise and find a way through.

Both adopt the same legislative stages, requiring MPs and Peers to approve the Bill as a whole, as well as the detail. If the Lords were not entitled to take a position on any Bill, then second and third reading would simply not exist.

The second major convention of the Lords is the Salisbury-Addison Convention, which holds that the Lords does not try to vote down at second or third reading a government bill which implements a manifesto commitment. That convention is founded, as Viscount Cranborne spelt out in the 1940s, on the principle that ‘it would be constitutionally wrong, to oppose proposals which have been put before the electorate’.

In the case of the Assisted Dying/Suicide Bill, these conditions are not met. Labour’s manifesto made no reference to assisted suicide nor assisted dying. Nor is this a Government Bill, despite the Prime Minister’s personal support for the legislation. At every stage of the Bill’s passage through the Commons, ministers told MPs that the Government is neutral on the Bill and the Bill represents the policy intent of the sponsor and not ministers.

The Noble Lords are also entitled to feel frustrated that Lord Falconer expects the more diligent of the two Houses to cut short scrutiny. On legislation of any significance the Lords will typically take twice the time that the Commons does.

The Commons took 15 days in Committee, two days for Report stage, and a day for Third Reading. The brevity of report stage was achieved only by curtailing debate, and the procedural controls that exist in the Commons. As such, while more than 90 concerns were identified by MPs at report stage, 80 were not even selected for a decision, eight were rejected, and just two that were not in Kim Leadbeater’s name were accepted.

If the sponsors of the Bill had been serious about securing the quick passage of the Bill through the Lords, more work should have been done in the Commons to ease the responsibility of the second House.

The Lords should also be comforted that the end of the session is penciled in for May 2026. This means that they can take the time to look at the detail of the legislation.

The thirteen sitting Fridays set aside in the Commons for the consideration of private members bills will have already run their course before second reading, which is due to take place on 12 September. The Lords is therefore under no pressure to return the Bill to meet a specific date, and it is the Government that will need to makeshift – should it chose to do so – to provide more time when the Bill completes its passage through the Lords. Nor is there any impact on the Government programme as the Bill can be dealt with on sitting Fridays, while Government legislation steadily progresses on other days.

Finally, we turn to the risk that the Lords are not done with the Bill by the time the session ends. This is plausible: there might be simply too many problems to patch, particularly in the absence of any consultative work to guide deliberations.

Here all sides should take comfort in the existence of the Parliament Acts and the specific provisions. The Royal Commission on Lords Reform concluded that the Parliament Acts – which enable the Commons to ‘achieve almost any result it desired’ – provided ‘another reason for the existence of a second chamber sufficiently confident and authoritative to require the House of Commons, at the very least, to think again’.

Should the Bill flounder in the Lords with too many unanswered questions, it would be perfectly permissible for the Government to take responsibility for setting up a Commission or Committee similar to the Warnock Commission or Peel Committee for IVF and Abortion to test the validity of the provisions and the policy approach taken in the Bill. If it was established that the Bill was safe, MPs could return with the same Bill. If the Bill was established as inadequate, a revised version could be developed.

In the former scenario, Peers need not worry that amendments made the first-time round would be lost if the Parliament Acts were used. The Acts and Erskine May are clear that if the Bill were to be reintroduced a second time, it can include amendments ‘made by the House of Lords in the former bill in the preceding session’; and if the Commons wished to propose further amendments recognising the debates in the Lords and indicating that the Commons is prepared to compromise, the Commons could also suggest these for insertion into the Bill.

On three occasions, bills have been introduced in a second successive parliamentary session to potentially allow the Parliament Acts to be used – only for the Lords to agree to the bills, with the passage of time helping to establish a way forward.

There are more than adequate mechanisms for the Commons to prevail should it wish to do so, but the Lords must not be bludgeoned into signing off a Bill of such complexity and significance. To do so is to abdicate responsibility and risks sacrificing some people, particularly the vulnerable, to secure the choice for others.

Comments