Choosing a new pope has more in common than you might expect with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) congress’s system for picking a new general secretary. Both processes are autocratic, secret, and rigid; they focus on the leader’s infallibility, and involve a lack of succession planning. And women don’t get a look in. China’s president Xi Jinping commands over 1.3 billion souls; so, too, will the new pope. He will also own the allegiance of an estimated 12 million Chinese. But how will he exercise his pastoral care and oversight?

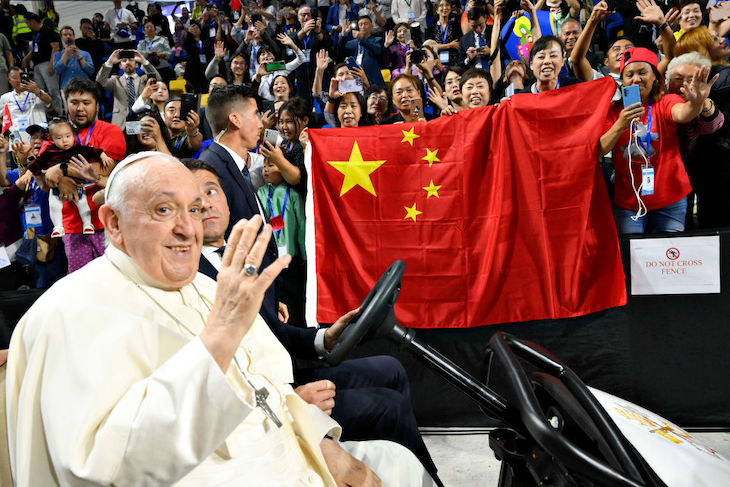

Pope Francis, who was laid to rest yesterday following his death on Monday, had a ‘thing’ about China. He was keen – desperate perhaps – to visit the country. But the nearest he got was to fly over China on his visit to Mongolia and South Korea in 2014, permission not granted to his predecessor John Paul II on a similar Asian trip. From the air, Pope Francis messaged Xi Jinping, ‘Upon entering Chinese airspace, I extend my best wishes to your excellency and your fellow citizens, and I invoke divine blessings of peace and well-being upon the nation.’ Xi Jinping did not wave or waver as the Pope passed over.

No doubt Francis’ interest in China centred on saving more souls than the current mere hundredth of the Chinese population. He was worried too about schism between the CCP-controlled Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association and the ‘underground church’. Bishops of the former were being appointed by the Chinese church and not the pope. But Francis may also have had a personal interest. A Jesuit, Francis had a particular regard for Matteo Ricci, also a Jesuit, who was a missionary in China in the 16th century. Ricci’s mastery of Chinese, mathematics and astronomy ensured him a warmer tolerance than extended to many other missionaries. In the view of another Catholic – but one less welcome to Beijing – the ex-governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, who met Francis on several occasions, Francis probably wished to canonise Ricci during a visit to China.

It is hard to envisage Xi welcoming either Francis or the new pope to China. He is a jealous god: his people owe loyalty only to the ‘core’ of the CCP – Xi himself – certainly not to a foreigner, and moreover one historically implicated in China’s ‘century of humiliation’ at the hands of imperial powers. Since the United Front Work Department conference of 2015, Xi has been banging the drum of the ‘sinicisation of religion’. Never mind the contradiction of an atheist regime wanting to synthesise the worship of a non-existent god with China’s cultural traditions, any more than its wanting to oversee the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, for the CCP, religion is politics.

And Xi is rather good at politics. In fact, rather better than Pope Francis. In 2018, the Vatican and China signed an agreement, since renewed in 2020, 2022 and 2024. The deal has never been disclosed, other than the very Chinese arrangement for selecting bishops: the pope is presented with a name which he ratifies, or could in theory reject. This is similar to Chinese democracy: you get a vote, but only for my candidate.

The agreement has gone some way towards uniting the official and ‘underground’ churches in that bishops are mutually agreed. But, as ever, the CCP has hardly stuck to the deal. It has appointed bishops without consulting Rome, including in one case to a diocese not recognised by the Vatican; and it has ensured that ‘underground’ bishops have stepped down from posts and become ‘associate’ bishops – under a compliant superior who allows them no voice. As the long-suffering Cardinal Zen of Hong Kong has said, it is a delusion that you can do a deal to which the CCP will adhere. This is particularly so in areas where the interests of the CCP conflict with the other party. Xi peppers his speeches and ‘thoughts’ with references to ‘forging the soul’. Which is also the business of popes.

There is no evidence that since the Vatican signed its deal with Beijing persecution of Christians has waned. On the contrary, Xi has been quite clear that control over religion is to be strengthened. It is also shameful that Francis has spoken out against the problems and persecutions taking place all over the world, but apart from one small reference in a book, has never mentioned the Chinese crimes against humanity committed in Xinjiang or Tibet. His Christmas Day 2020 Urbi et Orbi address referenced the Rohingya, the Middle East and Africa, but not China. It is almost beyond belief. Literally.

Will the new pope continue to ‘play the long game’ – naivety which the Chinese are masters at exploiting? The answer is that he probably will. The 2018 ‘deal’ was again renewed at the end of 2024, this time for four, rather than two, years. And the pope will have other more pressing matters to consider: setting forth his theological vision, reconciling conservative and progressive wings of the church, communion for the divorced, gay marriage, the ordination of women, financial scandals.

But to echo Harold Macmillan, there are “events, dear boy, events”. What if the Dalai Lama, now 90, dies in the near future and there is severe repression in Tibet? Can a religious leader such as the pope keep silent? Or what if tensions in the Taiwan strait boils over? The Vatican is the only European state with diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Can it overlook a threat to the freedom of 23 million people? And what if, for some now unfathomable reason, Donald Trump and JD Vance (a Catholic convert) perceive the Vatican as taking the wrong side in the new cold war?

Papal personality may also play a part, just as it seems to have done with Francis. If Cardinal Parolin is chosen, it is possible that he may be, in Chris Patten’s words, ‘institutionally wedded to the China deal’, even if, highly competent statesman that he is, he may be disappointed with what has been achieved so far. Cardinal Luis Tagle is another frontrunner. The CCP will be interested in his personal background and how it might play. His grandfather was Chinese.

Whoever becomes pope, it is hard to see him achieving what eluded his predecessor. Francis never managed to fulfil his desire to set foot in China. He took his papal name from Saint Francis of Assisi, but perhaps he should have named himself after another famous Saint Francis and missionary, Francis Xavier, who tried desperately to enter China. He died in 1552 on a small island off the coast of Guangdong, still waiting for permission to enter the celestial kingdom.

Comments