Japan’s Olympics have got off to the worst possible start. The captain of their women’s gymnastics team Shoko Miyata has withdrawn, or more accurately been obliged to withdraw, after admitting breaking the team’s code of conduct while at their training camp in Monaco.

Her Olympic dream is over and she leaves in disgrace. So, what was this unacceptable behaviour? Well, it appears Miyata smoked a cigarette and drank alcohol (once, for each). Smoking and drinking are prohibited for anyone under the age of 20 in Japan. Miyata is 19.

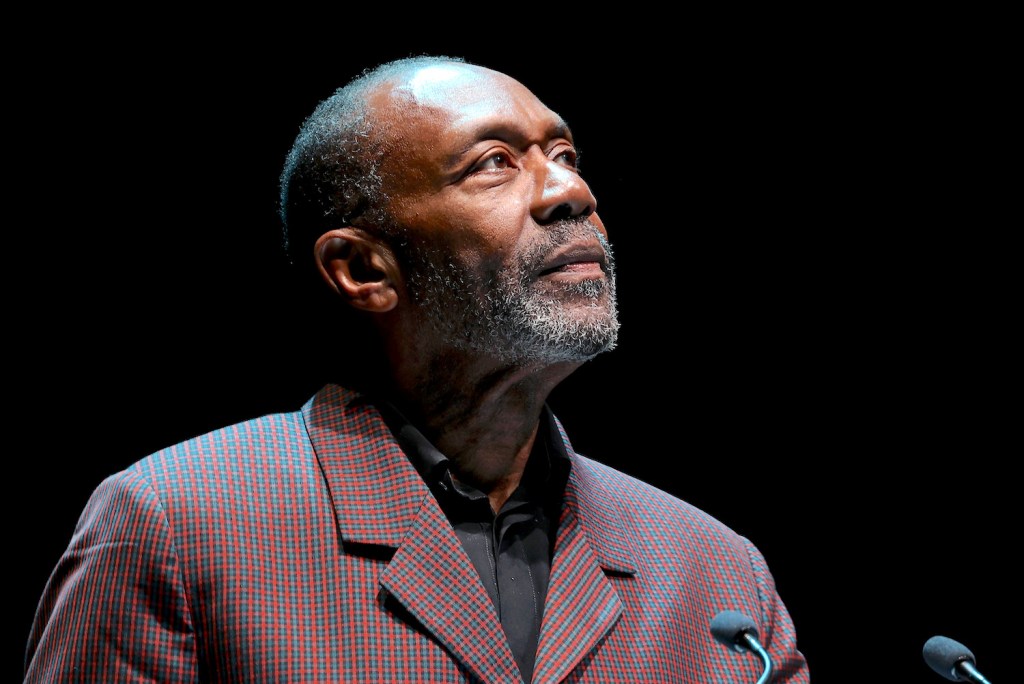

Miyata’s Olympic dream is over and she leaves in disgrace

JGA’s (Japanese Gymnastic Association) president Tadashi Fujita offered a grovelling apology ‘from the bottom of our hearts’ for the scandal while employing the deepest bow of shame (the ‘dogeza’) at a news conference. Alongside him was Miyata’s similarly contrite personal coach Mutsumi Harada.

Neither the fact that the offences appear to have occurred just once, and outside of Japan, nor that they were apparently due to ‘numerous pressures from the competitive targets that had been set’ (according to the athlete) seem to have been taken into account. She broke the rules. And she’s out.

Rarely has the huge differences between approaches to law and order and proportionate punishments between Japan and the UK been more starkly illustrated. Rishi Sunak may have had an age-related plan to phase out smoking – and Labour have declared an aim to ban the practice outright – but it is impossible to imagine a young woman in the UK being so severely punished for a bit of what appears to be either youthful exuberance or a stress induced measure to calm her nerves.

There has been plenty of criticism of the decision here in Japan, and sympathy for Miyata, though mainly, it must be said, by incredulous foreigners. Isn’t a bit over the top? Wouldn’t a warning would have been sufficient? Who exactly was hurt by her actions? On the surface it certainly looks like a gold medal should be awarded for stupidity and rigidity to the JGA.

But such reactions, though understandable, reveal an ignorance of the Japanese mindset. Things that seem trivial elsewhere are taken extremely seriously here, especially when matters of reputation, honour and honesty are concerned – tip to anyone considering living in Japan (especially if you are contemplating a romantic relationship with a local) phrases like ‘Is it really such a big deal?’; ‘So what?’; or ‘get over it’ are almost untranslatable.

The protection of societal harmony is paramount, easily trumping any personal circumstances or sympathy for an individual who is seen to break the rules, however young. Miyata is really being punished as a representative of her country (literally in sporting terms and figuratively in terms of Japan as a whole). She has let the side down, with the side being Japan.

The Japanese believe bad behaviour needs to be nipped in the bud, lest it leads to a spiral of depravity that hurts not only you but those around you. Let someone off smoking when it is clearly against the rules and you will embolden others to follow suit and perhaps embark on a pathway to more harmful behaviour. It is an attitude that once prevailed in the UK, but has almost (the encouragingly hefty sentences meted out to the Just Stop Oil disruptors is an exception) disappeared.

You would need a heart of pure granite not to feel sorry for Shoko Miyata though, and one would hope for a path back for this talented athlete (she probably will be able to rebuild her career). But if you think that her treatment is absurdly harsh, it is worth pausing to reflect on how a zero-tolerance approach to rule breaking can be shown to have served Japan well in a related context.

Japan has an annual prevalence rate of marijuana use of 0.10 (2019) one of the lowest figures in the developed world (one seventieth of the UK’s figure). There were 6,000 drug related deaths in England, Scotland and Wales in 2022; Japan doesn’t even keep figures as the numbers are so low. Japan simply doesn’t have a drugs problem – largely thanks to the harshness of the penalties (for possession as well as dealing) and the likelihood of being caught (very high).

How successfully Japanese youth has been kept on the straight and narrow in this respect was brought home to me recently when I was teaching a discussion class at my university. A group asked me if I thought strict rules and harsh punishments were necessary. I said yes, sometimes, citing drug laws in Japan as a shining example of such a policy working effectively.

Consider, I said, how many students at this university (which has 14,000 students) smoke marijuana. ‘You probably know better than me but I would imagine it is very, very few.’

‘No, you’re wrong’ said one girl rather forcefully, which took me aback, until she added…

‘It’s not very few. It’s zero.’

Comments