Last year, marking the tenth anniversary of Scotland’s independence referendum, I wrote an article for The Spectator looking at the state of Scotland’s political conversation and the prospects for the cause of independence a decade on from defeat.

After setting out why I thought MSPs ought to pass a budget that crossed the nationalist-unionist divide, softening the intense tribalism that has become a hallmark of parliamentary exchange, I also cast an eye forward to next year’s Holyrood election, in which no party is likely to have overall control. Recent polling trends show that Reform UK are hoovering up support from disillusioned Conservative and Labour voters alike, with Nigel Farage’s party likely to take seats in Scotland’s devolved legislature.

The trend also shows the SNP remaining the largest party – albeit with fewer seats than it occupies now – and Labour’s dream of turning Bute House red, after a long 19-year winter, looking increasingly distant thanks to Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves.

In such a parliament of minorities, I suggested that Scotland’s two dominant parties of the centre-left – the SNP and Scottish Labour – could change Scotland’s political conversation overnight by forming a governing coalition. Unthinkable, I hear you say. Well, no. Not quite.

In what was only a semi-serious idea posed in passing; it is now talked about openly across Scottish politics. That is not to say that it is necessarily likely – neither party can be seen to advocate it this side of an election – but that it would have been an unthinkable discussion a decade ago.

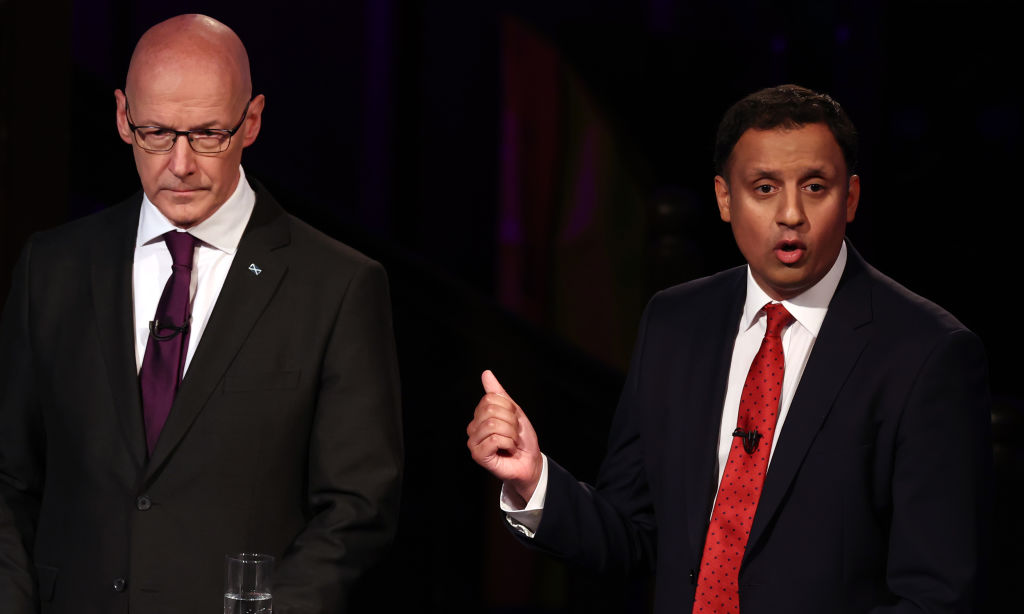

As recently as last week, First Minister John Swinney was asked if he would support a coalition with Labour. What he didn’t say was more interesting than what he did.

After a jolly chuckle, the SNP Leader said: “Well, I’m all for bringing people together, but let’s keep our feet on the ground here… I think I’ll just, in all these things, I think I’m best to just leave it to the public to come to their conclusions in the 2026 elections, and we’ll see where we get to after that.” Not a no, then.

Public attitudes to such an accord between the bitter foes make for interesting reading. A recent Survation poll found that 33 per cent of respondents would support such an agreement, making it a more popular prospect than another deal with the Scottish Greens – which, given how that coalition was nuked by the Former First Minister, would be unlikely to be endorsed by the membership of either party any time soon.

In the stagnant landscape of Scottish politics, such a grand coalition would breathe fresh life into the public discourse and could prove a powerful and robust alternative to the rising populist right, to which Scotland is not immune.

The battle lines between Labour and the SNP have been drawn with passionate intensity over decades, and there would be substantial howling and opposition within each party to such a pact. Yet, in Scotland today, where public services, our economy, our society and public realm need a modernising upgrade that’s well beyond the command of a minority government, such rigid demarcations serve neither party nor country.

For Labour, the benefits are obvious. It would end the party’s long spell in opposition and show a willingness to transcend outdated political boundaries – and after a tumultuous start to its recent return to power in Whitehall, it’s difficult to see what the party would have to lose. A coalition that was underpinned by a commitment to social justice, economic prosperity, improved living standards and high-functioning public services is surely something they would want to be part of?

The SNP could gain significant strategic advantages. While independence remains the ultimate goal, a constructive role as the senior partner in a new governing alliance could advance the party’s broader objectives. By proving themselves as pragmatic partners in government, the party could rebuild the reputation it once enjoyed as a ministry with national credibility amongst voters beyond their core base – something that has taken a bruising in recent years, and is crucial for any party that aspires to statehood.

When I first floated the idea, a number of friends in both parties told me I was mad

The Scottish government could also seek to secure positive movement on many policy fronts – such as the bespoke graduate Visa that John Swinney called for last week – and on the constitutional question, finally codifying in law the circumstances in which Scottish voters could revisit a referendum once again. The First Minister has already signalled that his thinking is moving in that direction.

Critics will inevitably decry such a pact, and opponents will dismiss it as political opportunism or Holyrood bubble elitism. Yet the real opportunists are those who want to maintain and exploit artificial divisions, re-running Scottish politics on a constant feedback loop.

This is not about surrendering individual party identities and political traditions, but honouring the promise of what devolution was always meant to be about: creating a new political architecture that reflects the complexity of modern Scotland.

When I first floated the idea, a number of friends in both parties told me I was mad. But just as many, also from both parties, told me they thought it had merit.

Next year’s Holyrood result is set to be a messy one – a parliament where no party clearly wins, but all clearly lose. An alliance of Scotland’s two socially democratic parties could be the circuit breaker Scotland needs.

Comments