I used to think that you could spot a literary classic by identifying certain salient characteristics: the writing would need literary quality, for example; the book would have had some historical significance; it would have an enduring reputation among scholars and general readers. But each rule threw up exceptions. Darwin’s The Origin of Species is not an obviously ‘literary’ text. E.M. Forster’s Maurice was first published six decades after it was written. The Song of Kieu, the greatest work of Vietnamese literature, is virtually unknown outside Vietnam. And yet all of these books are classics. Over time I have come to agree with Ezra Pound’s warning at the start of his ABC of Reading (1934). ‘A classic is classic not because it conforms to certain structural rules, or fits certain definitions (of which its author had quite probably never heard),’ he writes. ‘It is classic because of a certain eternal and irrepressible freshness.’ Pound rightly identified an internal rather than an external quality: the definition rests on an ineffable element of the reading experience.

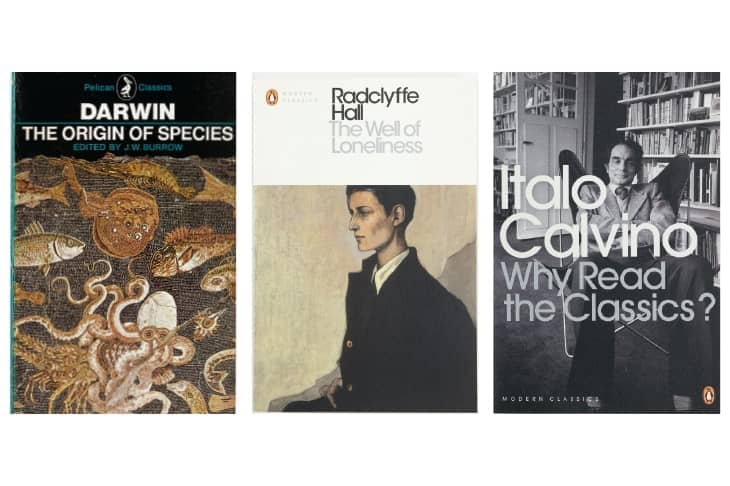

Of course, it may take time for a classic to be recognised as such. The Great Gatsby was famously snubbed by several critics; Moby-Dick was widely panned in America; in Britain every copy of The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall was destroyed, with one critic saying, ‘I would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel’; Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was burned by the Nazis; Flaubert’s Madame Bovary was prohibited by the Catholic Church; Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice is still forbidden in the detainee library at Guantánamo Bay.

Perhaps time does have to pass — a book has to endure in order to qualify, and in the meantime we use ‘modern classics’ to identify promising candidates. A modern classic has the same power and vitality as a classic, but it is younger: it is still speaking to the age through which we are living. As readers we share the concerns it addresses, which makes it urgent and exciting to read, but only time will tell if those issues remain fresh after 50 or 100 years or more; if it will graduate to full classic status. As for the ‘instant classic’, I find it almost impossible to pick out contemporary books that may become the classics of the future. My hunch, though, is that it will be those by the game-changers, the genre-benders and the iconoclasts, people such as David Foster Wallace, Hilary Mantel, George Saunders, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Colson Whitehead.

It can also work the other way: books can cease to be classics. For most of the 20th century, paperback books were printed lithographically on expensive presses, which meant that a minimum print run was required to make reprints viable. If a title wasn’t selling, it would not get reprinted,so there was a form of natural selection. Classics remained in print only if readers were buying them. For instance, titles that have ceased to be Penguin Classics over the years include John Aubrey’s Brief Lives, Benjamin Disraeli’s Sybil, Amelia by Henry Fielding, Carmen by Prosper Mérimée, The Maias by Eça de Queirós and Strindberg’s From an Occult Diary.

Today, however, the situation is different. Digital printing means it is economical to print short runs, even to print on demand, so there is seldom a practical reason for a classic to go out of print. But this raises a different issue: the prospect of an unweeded garden. Does a book need to have readers in order to qualify as a classic? In which case, should publishers be pruning titles that don’t sell?

Titles that have ceased to be Penguin Classics include John Aubrey’s Brief Lives and Benjamin Disraeli’s Sybil

Being a classic is not necessarily desirable, of course. ‘Definition of a classic,’ said Mark Twain in 1900: ‘Something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.’ Classics are all too often associated with worthiness and schoolwork, with eating one’s greens. ‘Why, before long I shall become a classic!’ exclaims a novelist in one of Edith Wharton’s short stories. ‘Bound in sets and kept on the top book-shelf — brr, doesn’t that sound freezing?’

The problem is that classics have traditionally been associated with the concept of a canon. In 1909, the outgoing president of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, launched a 50-volume set of Harvard Classics under the title Dr Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf of Books. This was a grand attempt to supply ‘such knowledge of ancient and modern literature as seemed essential to the 20th-century idea of a cultivated man’. But across the 23,000 pages, the 300 authors represented are exclusively white and overwhelmingly male. He omitted novelists like Jane Austen, Mary Shelley and Charlotte Brontë; campaigners like Mary Wollstonecraft, Frederick Douglass and W.E.B Du Bois; poets like Rumi and Hafez. What seemed ‘essential’ in 1909 no longer seems fit for purpose today.

We need to move beyond the idea of a universal canon. There are as many canons as there are cultures, as many as there are readers. ‘A culture’s canon is an evolving consensus of individual canons,’ the novelist A.S. Byatt wrote. This is demonstrated by the explosion of classics published in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Ten years after the Penguin Classics series was founded in 1946, the editors were concerned about its future: ‘How many more titles in the classical literature of the world are there?’ wondered the editor-in-chief, when the series comprised 60 volumes. He might have been surprised to discover that today there are nearly 2,500 titles published as Penguin Classics and Modern Classics, and hundreds more published by other imprints. Alan Bennett defined a classic as ‘a book everyone is assumed to have read and often thinks they have read themselves’. Looking at the sheer number of ‘classics’ around today, his statement rings true: all of us have large gaps in our reading and it is easy to feel insecure when those gaps include ‘classics’.

This ultra-saturation of the classics market may seem intimidating, but only if we think of classics as a duty imposed from above. Today’s excess should be welcomed, because it allows readers the freedom to range from Chinua Achebe to Svetlana Alexievich, Yevgeny Zamyatin to Stefan Zweig, exploring and assembling their own idiosyncratic lists of essential books. As the Italian writer Italo Calvino said in 1981: ‘All that can be done is for each one of us to invent our own ideal library of classics.’ We need to shift from canon-building to cartography: publishers, critics and scholars should act as guides to the blossoming literary landscape, signposting areas of outstanding natural beauty and encouraging readers to roam, chase butterflies and scale the literary heights where they can marvel at unforeseen vistas of future possibilities. We may not be able to explore every rabbit hole in our lifetime, but we can still have the time of our lives in the wonderland of books. As Calvino said: ‘It is no use reading classics out of a sense of duty or respect, we should only read them for love.’

Henry Eliot’s The Penguin Modern Classics Book (Particular Books) is out now.

Comments