Benedict Allen has narrated this article for you to listen to.

I’m not altogether a fan of what the writer Sara Wheeler has called the Big Willie school of expeditions. ‘To me,’ I once intoned loftily, ‘exploration is not about conquering nature or planting flags or going where no one’s gone before in order to make a mark. Rather the opposite.’ It’s more about a spirit of inquiry, I went on. If anything, the place should make its mark on you.

How then, do we want our explorers to be? The sort with steely eyes and frosted brow who silently trudges their way poleward despite the odds – though it’s never quite clear any more what they’re usefully discovering? Or would we rather have the boffin – a bespectacled specialist, say, in puffer jacket who genuinely advances humanity’s knowledge while overwintering in a prefab cabin, but frankly risks being a bit, well, dull?

If it’s not an explorer hacking off his frostbitten toes, it’s Nansen or Amundsen haunted by fear of failure

Erling Kagge is the former sort. Known for being the first person to bag not only the South and North Pole but Everest too, there’s no questioning his stamina and intent. Neil Shubin, who we learn is the ‘Robert R. Bensley Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy’ at the University of Chicago, is the latter. Neither is a slouch.

Take Shubin. In careful, unimpassioned prose he presents an overview of those at the ice face, as it were, of polar research. There’s the break up of the Larsen B ice shelf, as documented by Nasa’s Terra satellite. Then there’s Willi Dansgaard, the Danish physicist whose diligent analysis of ice cores revealed to us the alarming rise through the centuries of our planet’s temperatures. Next along, a Japanese team questing for meteorites; others tracking the prints of bulky dinosaurs; still others investigating the use by various organisms of antifreeze compounds. We hear of worms that get through hard times by transforming into brittle strands of sugary glass, reanimating maybe decades later when temperatures are more favourable. And, should you want more, there are 20 pages of dense notes and references. All to the good, then. Fascinating. Important, too. Yet, out there in the stark, cold ends of our planet as portrayed by the good professor, there’s something missing. Drama, is it? Or ego? Folly, certainly.

Kagge, by contrast, is absorbing from the start. We are a crazy, messed-up species – that much is known already. But where better to display our workings – the best and worst of us – than on a wide open, icy stage, where the sun at times emits no warmth? You might not think that the continual questing by a few obsessive individuals for a northerly point on the drifting pack ice would make for good reading – we should surely be tiring now of these blinkered and largely irrelevant polar athletes – yet it seems there’s nothing better than a fairly pointless journey into the middle of nowhere to tell us about ourselves.

Out there, our heroes and anti-heroes are stripped down to essentials, like King Lear exposed on the heath. The quest for knowledge turns inward and becomes a quest for self-knowledge – and human improvement. Success lies in being a better tactician, a finer operator in the face of adversity, as he – and it nearly always is ‘he’ – achieves ever higher levels of diligence, preparation and also (you fondly hope) humility.

Of course, when it comes to striding through uniform whiteness it is the inner, psychological journey – or at least our protagonists’ colourful antics – that must deliver. Tales of polar trekkers become character-driven. It helps that the art of dicing with death is quite intriguing in itself, as are great feats of self-delusion. And here they are, a tally of stubborn, maddened strivers who from the time of the Vikings – they called the Arctic hinterlands ‘home of the fog’ – have sallied forth and, to a greater or lesser extent, suffered.

If it’s not an explorer hacking off his frostbitten toes – the act was hard but, we gather, not as hard to bear as the reeking smell of gangrene that had preceded it – then it’s the great Fridtjof Nansen and his protégé Roald Amundsen haunted by ‘a perpetual fear of failure’. The ice floes become a telling backdrop to national rivalry, false pride and hubris – deftly illustrated by the Italian aviator Umberto Nobile’s second (1928) endeavour with an airship, much trumpeted by the fascist Mussolini. It crashed on to the ice, lost its gondola and the now buoyant superstructure rapidly ascended, along with six crew members, never to be seen again.

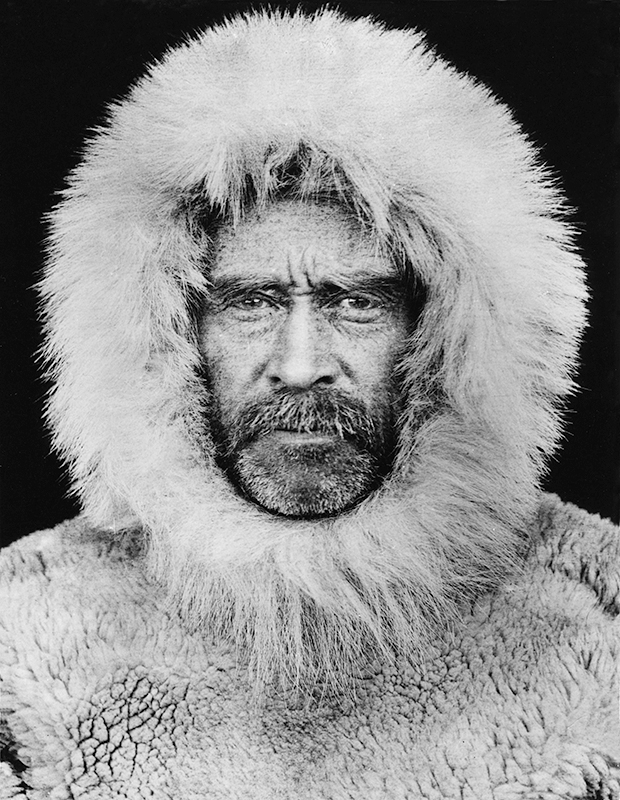

Looming large in a crowded field of egotists is the ghastly Admiral Peary, a foremost claimant to the North Pole who also claimed quite a few Inuit ladies en route. Over the course of four years in the vicinity of one perceived rival, the Arctic navigator Otto Sverdrup, the American felt unable to take off his mittens to shake the Norwegian’s hand.

Helpfully, all these boreal goings-on are interlaced with Kagge’s own hard-won experience:

When it is between -40˚ and -50˚C outside the tent it is all too tempting to stay in your sleeping bag for just another ten minutes rather than crawl out shivering and freeze like hell. That has been – and remains – the greatest challenge since polar exploration began.

And so to the present day, when our greatest pioneers are the sort brought to us by Shubin; from here, the ‘path of wonder and adventure’, as Kagge puts it, leads elsewhere, ‘past the North Pole to the moon and on into space’.

These books of very different persuasions each have their merits. They also share a schoolboy error, dubbing the august Royal Geographical Society ‘the Royal Geographic Society’. In Kagge’s case, it may be the fault of the translator. But you get the feeling that it is he, the one schooled not by academic rigour but the polar blizzard, who is the explorer who’ll be most niggled to have this pointed out.

Comments