Before the jukebox musical, back when Mamma Mia!, Jersey Boys and Viva Forever! were still dollar-shaped glints in an as-yet-unborn producer’s eye, there was the pasticcio opera. Literally a musical ‘pastry’ or ‘pie’, these brought together arias from different operas, often by different composers, in a single work, designed as a way of feeding an 18th-century public whose appetite for opera was greater than composers’ ability to sate it with new music.

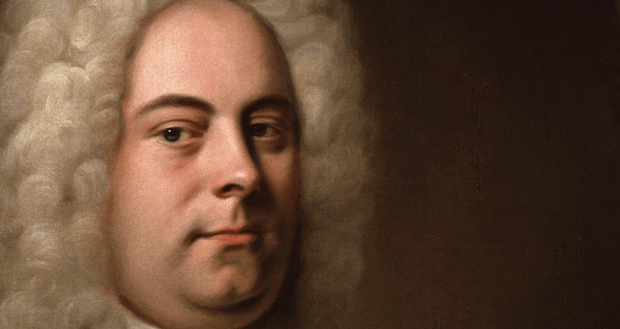

Everyone did it — Vivaldi, Mozart, Haydn, and of course that ultimate musical pragmatist Handel — but that didn’t make the practice any the more respectable, as one satirist’s pasticcio ‘recipe’ makes clear.

Pick out about an hundred Italian Airs from several Authors, good, or bad, it signifies nothing. Among these, make use of …such as please your Fancy best …When this is done, you must make a Bargain with some Mungril Italian Poet …then deliver it into the Hands of some Amanuensis, that understands Musick better than your self, to Transcribe the Score, and the Parts.

To 18th-century critics in thrall to the new psychological dramas of Metastasio this cut-and-paste approach was anathema, but what about a contemporary audience? Rather than risk hundreds of minor baroque curiosities, pasticcios offer us the chance to skip straight to the highlights — to get some 20 operas for the price of a single evening. The musical maths makes sense, but can an opera of best bits really add up to a satisfying whole? The London Handel Festival offered two different answers this week, with the modern UK premières of pasticcios Giove in Argo and Catone in Utica.

Giove is an oddity, one of only three pasticcios Handel produced of his own music. While the plot combines Ovid’s stories of Io (Iside, here) and Calisto, the score features arias from the composer’s London hits Faramondo, Ezio and Alcina, among others. If the result isn’t quite the ‘unsatisfactory hodgepodge’ it has famously been described as, then it’s not exactly elevated drama either. Tackled in the London Handel Festival’s typically colourful and irreverent style, mindful of a happy ending that’s more convenient than convincing, Giove might have fared better than it does when weighed down by director James Bonas’s overcomplicated vision.

Diana’s nymphs (of both sexes, curiously) are samurai by way of the Eastern Bloc, patrolling futuristic woods, into which Osiri (Nicholas Morton, unaccountably styled as a schoolboy on his D of E expedition) and the hapless Calisto and Iside (Sofia Larsson and Angela Simkin) stray. Direction calls fussy attention to da capos, demanding that the RCM’s student singers keep striving after non-existent naturalism when the real interest is all in the music.

This really is a fine score, with hits piling up until Act III almost topples over under their cumulative weight. We’re carried along on the swift speeds and stylish delivery of Laurence Cummings and his band, supporting the excellent student chorus and slightly more uneven cast. Simkin dominates — a mezzo with both power and a lovely range of expressive colour — matched for presence by Morton’s Osiri. Faced with the feisty Simkin and Larsson’s urgent (if sometimes underpowered) Calisto, it’s hard to see Peter Aisher’s Giove as a predatory seducer. Gifted here with some of Handel’s finest vocal writing, he fails to project anything like the authority achieved by the women, fatally unbalancing a score whose drama is already so secondary to its musical spectacle.

Handel’s Catone in Utica casts its musical net wider than Giove, incorporating arias by Vivaldi, Hasse, Porpora and Vinci into a framework provided loosely by a Leonardo Leo/Metastasio original. In this one-off concert performance by Opera Settecento, featuring neither surtitles nor freely available libretto, the Roman plot was frankly baffling, but it says a lot about the nature of pasticcio that it really didn’t matter.

With recitative slashed to the minimum and tragedy soft-pedalled in favour of tempestuous virtuosity, musical sensation was everything. Directing from the harpsichord, Tom Foster whipped his orchestra into a joyous frenzy, strings supplying all the rhetoric lost by the words in the thick acoustic of St George’s, Hanover Square, goading the superb young cast on to ever-greater agility. Handel Festival regular Emilie Renard was a boyishly believable Arbace, while bass-baritone Christopher Jacklin’s Cesare alternately thundered and shimmied in coloratura all the more thrilling for being so completely unexpected. Stealing hearts and laurels, though, was 2014 Ferrier Award-winner Christina Gansch. A 24-carat voice allied to real dramatic poise, at only 25 this soprano is already everything this repertoire was designed to showcase. Gesamtkunstwerk be damned; sometimes opera doesn’t need to be everything to be really something. Pasticcio’s empty virtuosity makes a star of music itself. When that music is as good as this, who needs or wants more?

Comments