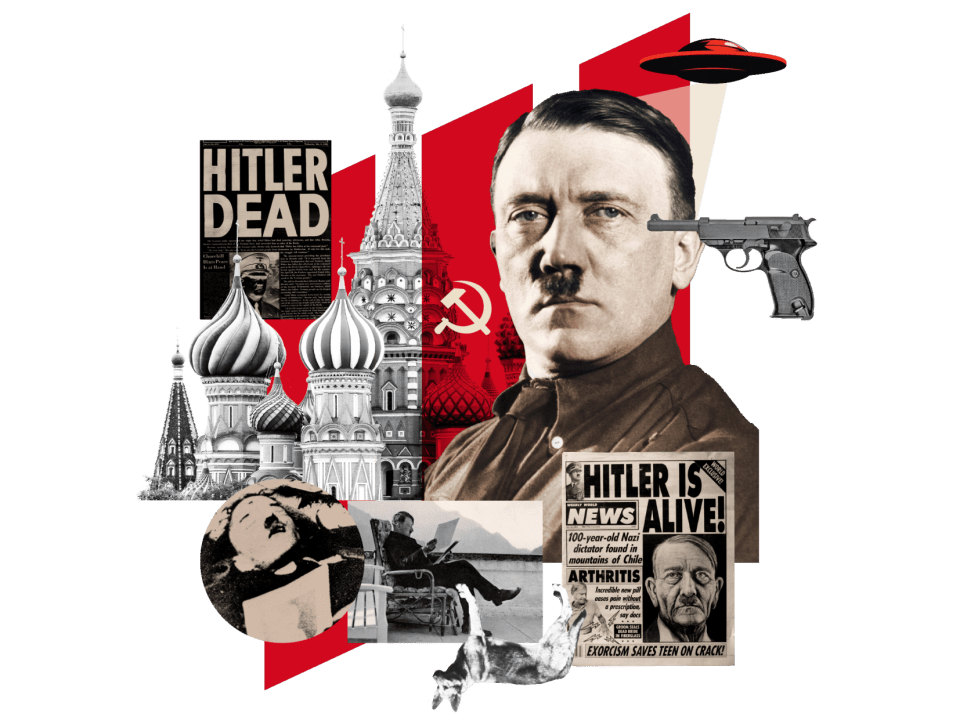

Eighty years ago, as Red Army shells rained down over Adolf Hitler’s Reich Chancellery garden, a group of his remaining friends and colleagues huddled under the block-shaped exit of his last grim command centre, the Führerbunker. Flames engulfed the bodies of the newlywed Mr and Mrs Hitler, casting a flickering light over the onlookers, who raised their arms in a final straight-armed salute.

The enduring cultural and political relevance of Hitler’s death hardly needs restating. It gave us online parodies of the rant scene in the film Downfall and, of course, a wild range of conspiracy theories.

I once hoped that my book Hitler’s Death: the Case Against Conspiracy might put an end to those. But four years after publication, when I was invited on to the History Channel to inform viewers that Hitler didn’t die in 1958 from an American nuclear explosion over Antarctica following a battle with alien technology, I found myself wondering why such ridiculous stories endure.

The truth is, there are still fascinating mysteries that surround Hitler’s death, and those mysteries can be partly blamed for the persistence of some conspiracy theories. Remarkably, even 80 years later, historians still can’t say for certain precisely how Hitler died. The main reason for this uncertainty is the messy state of the forensic evidence. Behind that mess lie the Russians.

The first Soviets who entered the Führerbunker on 2 May 1945 didn’t set about a serious forensic investigation. Instead, they pinched a load of Eva’s bras and walked back out with them. This set the tone for the Soviet investigations into Hitler’s suicide.

That afternoon, the Soviet counterintelligence organisation SMERSH (literally meaning ‘death to spies’) commenced their investigation into Hitler’s fate. At first, a lookalike corpse, one of many bodies scattered around the area, was falsely identified as Hitler. Soon realising their mistake, SMERSH re-exhumed the real remains of Adolf and Eva from a bomb crater in the Reich Chancellery garden. They were subjected to a postmortem examination on 8 May – VE Day.

Hitler’s autopsy is a strange thing. His organs were not dissected or tested to confirm the alleged cause of death – cyanide poisoning – but the remains of his German shepherd, Blondi, were. Only one unclear photograph of Hitler’s remains was taken. Still, SMERSH collected the most important piece of evidence for Moscow: Hitler’s teeth.

By the time the western Allies entered the bunker in the summer of 1945, what they found was not a well-controlled crime scene, but a looter’s paradise. A whole room was stuffed with Hitler’s belongings. British soldiers joined in and they could easily sneak things out under their jackets past the Russian guards. I had the pleasure of telling Nemone Lethbridge, the daughter of John Sydney Lethbridge (chief of the British Intelligence Division in Germany between 1945 and 1948), that her father took a postcard, signed by Hitler, from the top drawer of the Führer’s desk.

Joseph Stalin was not happy with the SMERSH investigation. Instead of sharing the embarrassing details with the West, he did something very odd. On the same day one of Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s staff officers told the world that Hitler had died by poisoning himself, Stalin said Hitler was alive. At the Potsdam Conference, he said Hitler could be in Spain or Argentina.

There is no document explaining why Stalin did this. But he was probably playing a political game. Saying Hitler was alive allowed him to undermine a perceived rival in Zhukov, attack hostile regimes abroad, and keep the inadequacies of the Soviet investigations to himself.

A Soviet accusation that Hitler could be hiding in the British zone of Germany finally inspired British intelligence to undertake their own detailed investigation into Hitler’s death. They chose the best man for the job. Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper was an experienced MI6 officer and the foremost British expert on Nazi intelligence organisations.

Trevor-Roper worked at speed with his American and British colleagues in Germany. His investigations brought together an array of witness and documentary evidence, producing a narrative of Hitler’s last days which remains authoritative today. After issuing impossible orders, raving about the ‘betrayals’ of those closest to him, marrying the woman he loved and dictating a final political testament which blamed the Jews for everything, Hitler shot himself. But even some of the evidence uncovered by British intelligence remains lost to history. I have been unable to locate Hitler’s engagement diary which Trevor-Roper used to verify certain times and dates, and historians still can’t say for certain who typed the fourth copy of Hitler’s will, which the Russians kept to themselves for years.

The Soviets found Trevor-Roper’s report ‘very interesting’, but they had nothing else to say on the matter. Probably incensed that the British had done a better job, Stalin secretly ordered another investigation into Hitler’s death, this time headed by the infamous NKVD, in 1946. That investigation unearthed a piece of skull damaged by a bullet. The NKVD findings suggested that Trevor-Roper was right, Hitler had shot himself. Weirdly, SMERSH refused to let the NKVD re-examine the remains they had uncovered. Historians can only theorise why.

In 2009 scientists from the University of Connecticut conducted DNA tests on the bullet-damaged piece of skull. The DNA results suggested that the skull was that of an unknown female. This inspired a new wave of conspiracy theories.

Red-faced Russian archivists argued that the DNA samples were taken without permission and disputed the validity of the results. In 2017, a team of French scientists examined the skull, jaw and teeth in Moscow. They suggested that the skull could still be Hitler’s, but they were not given permission to conduct any further DNA analysis.

Conspiracy theories thrive off uncertainty and Hitler’s chosen method of death reveals his character

Despite the regrettable state of the forensic evidence, we do know Hitler shot himself. Hitler’s dentists identified his jaws and teeth, and that identification has been confirmed by several forensic studies. Photos show blood on Hitler’s sofa where witnesses saw his body slumped over. The blood was tested, and it matched Hitler’s blood type. Witnesses describe only Hitler’s corpse being covered in blood, but Eva smelt of bitter almonds, indicating cyanide poisoning.

What we don’t know is whether Hitler shot himself and bit down on a cyanide capsule simultaneously. This is very unlikely due to the instantaneous nature of death by cyanide. But the most recent examination of Hitler’s teeth uncovered tiny blue deposits, suggesting the residue of a cyanide capsule.

This matters, because conspiracy theories thrive off uncertainty and Hitler’s chosen method of death reveals something of his character. Hitler’s death still has deep contemporary resonance, too.

In 2019 I called for an international team of scholars to conduct DNA tests on all the remains in Moscow in the interests of finding the truth. I would still like to see that happen one day. However, Russian propaganda – including the bizarre claims that Volodymyr Zelensky has purchased Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest and that Britain started the second world war – has shown Russia still can’t be trusted with historical truth.

Although the effort has always been international, Britain has arguably done more than any other country to solve the mysteries of Hitler’s death. When I think of Hitler’s death, the image which first comes to mind is not of Hitler ranting at his generals or even the Battle of Berlin. It is a picture of Winston Churchill on 16 July 1945, sitting on Hitler’s chair in front of the bunker exit, near where Hitler’s body had burned.

That’s because Hitler’s death not only represents the destruction of Nazi barbarism, but also the triumph of Britain. This is evident from the decisive role which Britain played in the second world war, the freedoms which Britain helped to preserve and the democratic state it helped to build in western Germany before its occupation of that land formally ended in 1955. We should remember this and take some pride in our history.

Luke Daly-Groves’s Hitler’s Death: the Case Against Conspiracy is out now.

Comments