What difference does the internet make? Critics blame it for a range of ills, from social collapse and child abuse to obesity. So shouldn’t we greet with some caution and even sadness the recent announcement that Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite broadband is to reach tiny Pitcairn Island in the Pacific Ocean, home to the handful of descendants from the 1789 mutiny on the Bounty? Will the advent of Zoom calls and the ability to stream The Crown turn this idyllic tribe into socially fractured, screen-obsessed time-wasters? Is high-speed connectivity the beginning of the end for this Pacific paradise?

I think not. Because this 38-strong community collapsed long before Musk was crowned the richest man in the world. It doesn’t take Starlink for paradise to turn sour.

Pitcairn is probably the most isolated inhabited place on our planet. Hover your finger above a map of the Pacific and somewhere in the middle of that vast blue blanket is a speck called Pitcairn – a mile-by-mile-and-a-half lump of volcanic rock more than 3,000 miles from the nearest landmass. It took a three-week voyage on a cargo vessel through the Panama Canal and across the ocean for me to reach it, clambering down the ship’s side on a Jacob’s ladder and into a longboat several miles offshore. Pitcairn has no natural harbour, no airstrip and no regular contact with the world beyond. Any online access has been slow and limited. Until now. Until Starlink.

When I was on the island, talking to the rest of the Earth was a challenge. The most reliable form of communication was VHF radio, so crackly long distance conversations were dotted with ‘Roger’ and ‘Over and out’. We linked up with amateur radio enthusiasts worldwide, in Texas or Torquay, who passed on our messages in more ordinary ways to the intended recipients. This radio was also used to call out to any passing ships spotted on the horizon. We’d invite them to anchor offshore, then we’d launch the longboat loaded with simple wooden carvings and pandanus woven baskets and exchange these for tinned food, electrical goods and DVDs.

When I was on the island, talking to the rest of the Earth was a challenge. The most reliable form of communication was VHF radio, so crackly long distance conversations were dotted with ‘Roger’ and ‘Over and out’

Unfortunately suffering square eyes is nothing new in Adamstown, the island’s only settlement. I remember those DVDs playing on a wall of several shoulder-to-shoulder giant screens cramped into a modest three-roomed corrugated iron-roofed home, continuing for as long as the intermittent island generator allowed. I watched more TV on Pitcairn than I ever did in London, including all three series of Twin Peaks, 48 episodes.

Nor, I imagine, will the island’s Body Mass Index figures change much. The Pitcairners are a small community of big people, largely due to a diet flavoured by the native sugar cane syrup. The island is also tough terrain – although little more than a mile square, most of that land is unreachable on foot, so going for a nice long walk will only take you in ever-decreasing circles. As a result, diabetes is prevalent. It’s also hard to manage as the nearest doctor is in New Zealand – a rough and unreliable ten-day sea voyage away.

The internet is often accused of encouraging and disseminating child pornography, but Pitcairn didn’t need access to abhorrent online content to be awash with abuse. Almost 20 years ago, seven men – two-thirds of the adult male population – were found guilty of child sex abuse and rape, including of toddlers. Other prosecutions followed. For the first time, police and social workers were put on board a ship and posted to do a stint on the island. It’s a sad story not of a bad people, but of the dangers of living in such a lonely place, whether the deep dark web has reached there or not.

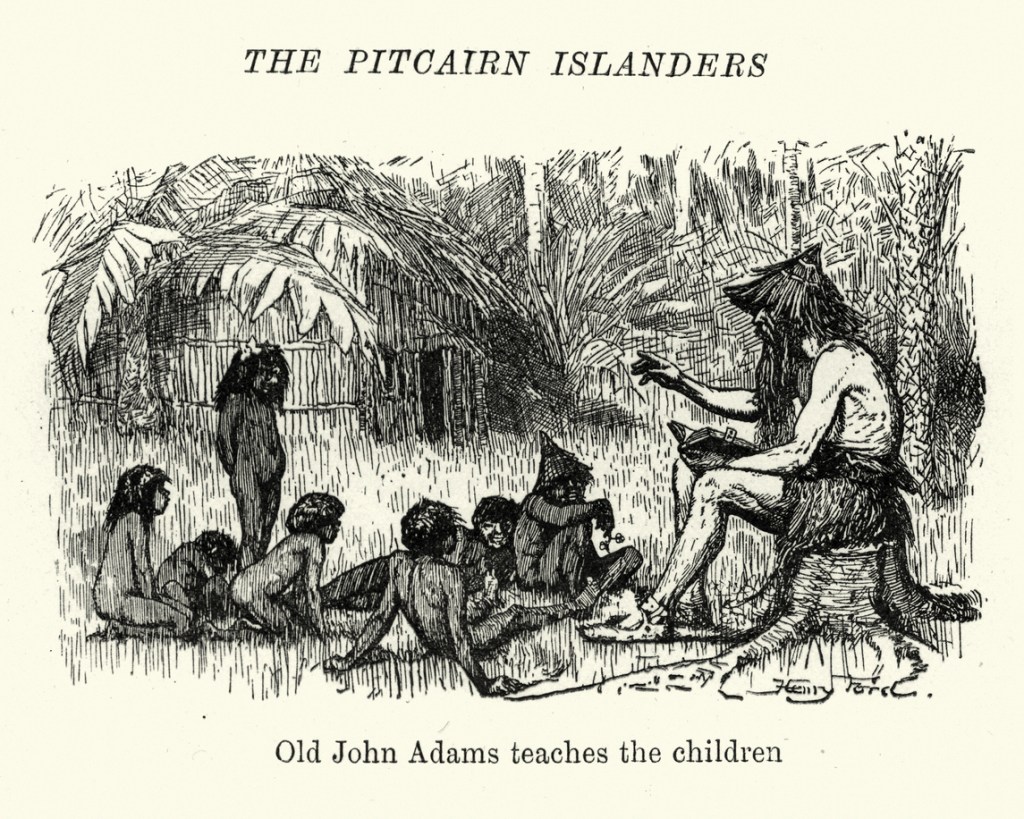

Social cohesion – often deemed another victim of the internet – has never been strong on Pitcairn. The island was born of a mutiny, and the Tahitian women who ended up on its rocky shore were more likely to have been entrapped and trafficked than to have gone willingly with the mutinous crew. For more than 20 years this British-Pacific islander community lay undiscovered by the world beyond. When a British frigate sailed by in 1814, there was only one mutineer, John Adams, left alive. Most of the men had murdered each other.

When I arrived two two centuries later, there were still divisions and feuds. Among the four families, two hadn’t spoken to each other for decades. No one really remembered why. Avoiding each other was impossible in such a small place so tensions were ever present. Once someone planted nails head-down in the muddy path outside their home so their neighbour would be injured if they attempted to trespass, in the knowledge they were a long, long way from a doctor. No one said who it was, or why. But everyone knew.

Pitcairn proves we don’t need Google or social media to become socially-divided, troubled screen addicts. The horrible truth is that technology doesn’t damn us: we’re perfectly capable of doing that all by ourselves.

Comments