The Philippines is the odd man out in Asia, a predominantly Catholic country colonised first by Spain, then the United States. An archipelago with more than 2,000 inhabited islands on the cusp of the Indian and Pacific oceans, its strategic location is obvious. Yet it receives scant coverage in the British media beyond its natural disasters, the flamboyance of its leaders, whether Imelda Marcos or Rodrigo Duterte, and its long-running Marxist and Muslim insurrections. On a more mundane level, our encounter with its people will most likely be through the care they provide within the NHS.

Philip Bowring, a former editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, for many years the outstanding English-language magazine on Asia, provides a much fuller picture. His book divides into two parts. The first is a potted history of the country up to the end of Duterte’s term of office; the second analyses different aspects of Filipino society, whether education, the economy, migration, the Muslim minority, Christianity, domestic politics or foreign affairs.

Against its neighbours in east and south-east Asia, the post-war Philippines measures up badly. Social development has been more impressive in Thailand and Indonesia, let alone South Korea and Taiwan. Education is underfunded, land reform half-hearted and large-scale manufacturing inadequate. Behind these weaknesses lies a failure of governance. The Philippines remains a vibrant democracy but its growth is vitiated by the hold on power maintained by a few families. ‘The domination of dynasts at every government level remains a roadblock to modernisation of the economy,’ Bowring writes.

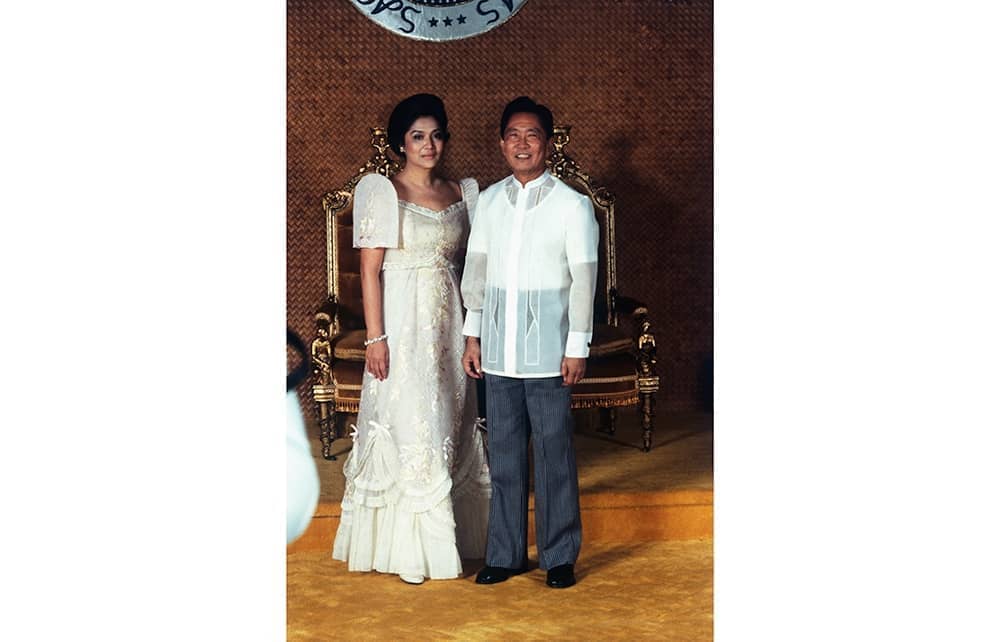

The front runner for the presidential election on 9 May is Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, the son of the dictator who was overthrown in a popular revolution in 1986. In the race for vice-president, who is elected on a separate ticket, Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of Rodrigo, leads the field. The main opponent of Marcos père was Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino, the scion of a landed family in Central Luzon. After his assassination, and the flight of Marcos, his widow, Cory, became president. Twenty-four years later their son, Benigno ‘Noynoy’, was elected to the same post.

His successor, Duterte, has been the country’s most notorious leader since the elder Marcos. During his term, which ends in June, his murderous bad-mouthing incited the extrajudicial killing of thousands of Filipinos in the so-called war on drugs, a scandal which led the International Criminal Court to open an investigation into possible crimes against humanity.

Countering the president’s argument that the Philippines was becoming a ‘narco-state’, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime classed its use of drugs as low compared with the global average. The government was also criticised for targeting petty pushers rather than the big barons.

Duterte came to power saying he would confront the old oligarchy and back the provinces against Manila by adopting a federal constitution. Neither pledge was fulfilled. He was a reluctant supporter of a bill, agreed by his predecessor Noynoy Aquino, to grant greater autonomy to the Muslim majority areas of Western Mindanao and Sulu in the south. In riding out the pandemic, the Philippines suffered from the incompetence of his appointees. On foreign policy he swung incoherently between the US, which the Philippines has long resented and envied, and the rising power of China, whose incursions in the South China Sea he first soft-pedalled in the hope of massive development aid, then appeared to backtrack. The legacy of his six-year term is both vicious and pitiable.

In 1973, a year after Marcos had declared martial law, the young Bowring wrote a feature on the Philippines for the FEER entitled ‘Asia’s Next Miracle?’. Nearly 50 years on, his answer must be no. He notes the persistence of poor governance, economic underperformance and the absence of strategic thinking on how to contain a resurgent China. Then there is the new challenge of rising sea levels to a country over a third of whose population lives in the largely low-lying northern areas of Manila, Central Luzon and Calabarzon.

His book is a dry read, packed with information but lacking the anecdotal colour which would help convey the easy-going, freewheeling and hospitable society he describes. There is, for example, nothing on the creative spirit of the Filipinos as expressed through their arts or their cooking. That, however, was evidently not Bowring’s brief. He has written a serious, well-researched survey of the Philippines, noted its manifold weaknesses and set them against what has been achieved in neighbouring countries. His is a welcome guide for the general reader to a country whose excesses are often difficult to fathom.

Finally, a word to the publisher. Devoting 18 pages to maps of each of the Philippines’ regions is not warranted by the text, and details on the map of contested areas in the South China Sea are so small as to be legible only through a magnifying glass.

Comments