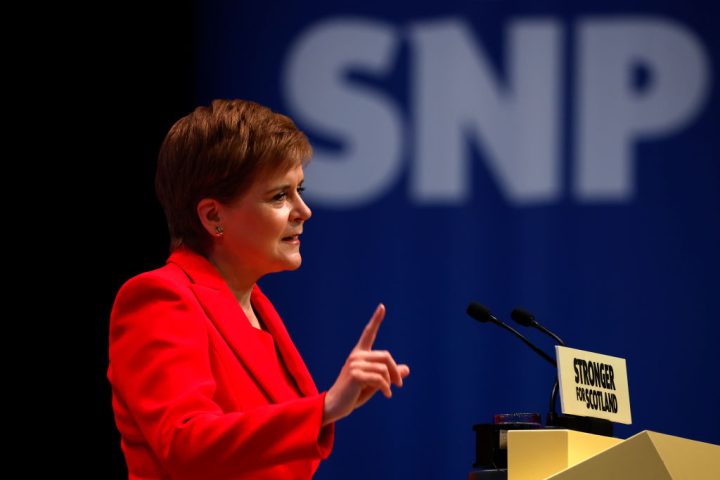

Dazed and confused by their leader’s sudden departure, Scottish nationalists are now deeply worried that Nicola Sturgeon has taken the independence dream with her. She hasn’t of course. Independence is a long game and there remain many true believers. However the chances of transforming the Scottish National party’s immense electoral success into a referendum on independence in the near term seem remote.

Some in the movement are wondering if the referendum route is still viable since it has been driven into a legal cul de sac by Nicola Sturgeon’s discredited idea of turning the next general election into a ‘de facto’ referendum on independence. That ploy is now surely dead.

The recently-installed Westminster leader of the SNP, Stephen Flynn, has suggested that the entire independence project needs to ‘take a breather’. It might be a long time before it regains its puff.

The immediate task of the next SNP leader will be to prevent a post-Sturgeon collapse in electoral support

The special conference scheduled for next month to debate the way forward has now been cancelled. It would likely have turned into a wake presided over by an undead leader since Sturgeon would still be formally in charge of proceedings.

The de facto referendum was anyway doomed to failure since the SNP has precious little chance of delivering more than 50 per cent of the vote in the general election of 2024 or thereabouts. The SNP didn’t even reach that figure in the ‘tsunami’ general election of 2015 when they won 56 out of 59 Scottish seats. With Sturgeon gone it is inconceivable that that result could be bettered.

The alternative Plan B, turning the 2026 Scottish parliamentary elections into a plebiscite, makes little more sense. What would be the point? The independence parties already have a mandate from previous Holyrood elections. The reality, as the Supreme Court pointed out in November, is that the Scottish parliament does not have the constitutional right to hold any referendum, de facto or not.

Many in the SNP were as bemused by Nicola Sturgeon’s legal shenanigans as they were with trans self-ID. Why ask an ‘English court’ to rule on this matter, they said. Wha’ daur meddle wi’ Scotland’s right to self-determination, said the voice if the nationalist street. Where was the passion, the vision, in these picky legal arguments?

SNP members had anyway become increasingly restive over their leadership’s failure to move the dial on independence despite piling up election victories. What’s the point of all those MPs and MSPs if they don’t bring independence any closer? They noted how Nicola Sturgeon declined to attend the large independence street demonstrations held in 2018 and 2019. Did she still believe?

That is an intriguing question that only the First Minister can answer. She always insisted that the only independence referendum worth having was as one authorised by Westminster under Section 30 of the Scotland Act. That was the only way to put the result ‘beyond legal challenge’ and ensure that Scotland’s newly independent status was recognised by international bodies like the European Union. But that route seemed very obviously barred by Westminster governments for the foreseeable future. It seemed a council of despair to true nationalists.

But Nicola Sturgeon was not up for any extra-legal or extra-parliamentary strategies, still less civil disobedience along Catalan lines. No wildcat referendums, no street confrontations, no occupation of UK government offices under her watch. We may see some of that now from frustrated nationalists as their anger boils over. A kind of tartan version of France’s Yellow Vest demos is a distinct possibility. But Scotland is not a revolutionary country and law-breaking antics would only turn canny Scots voters against the whole idea.

The immediate task of the next SNP leader will be to prevent a post-Sturgeon collapse in SNP electoral support. Who that leader will be is anyone’s guess. A measure of the problem is that the most widely tipped candidate, the finance secretary Kate Forbes, is on maternity leave and not even in parliament. She is also a religious conservative, a member of the Wee Free faith, who oppose things like same sex marriage and transgender recognition. The LGBTQIA+ cadres who have been so influential in the SNP leadership in recent years would revolt if Ms Forbes came anywhere near Bute House.

The other front runner, if he can be called that, is Angus Robertson MSP, the former Westminster leader. Capable and fluent he is regarded with some suspicion by supporters of nuclear disarmament in the SNP because of his conspicuous support for Nato, the nuclear alliance.

It is thought that Ash Regan, the former SNP community safety minister who resigned over gender reform, may put her hat in the ring. Though she too also would face fierce opposition from the many followers of Stonewall in the party.

Labour are understandably jubilant at the departure of Nicola Sturgeon, a politician they greatly respected if only in private. The leader of Scottish Labour, Anas Sarwar, is hoping that the tribulations in the governing party will turn Scottish voters back to their traditional party of choice. The SNP dominance of Scottish politics is actually very recent. In the 2010 general election, Labour returned 41 MPs in Scotland against the SNP’s 6.

However Scottish voters, especially the younger generation, have become used to voting SNP. They may not be all that engaged with the constitutional issues or the mechanics of independence – they just support their team. Voting SNP is just how you show you are a patriotic Scot.

Scots might indeed be relatively relaxed if the divisive referendum route to independence is laid aside for the time being. Nicola Sturgeon never properly addressed the problems of becoming independent post-Brexit: the hard border and currency issues. No one seems to have the intellectual will to bring the 2014 independence prospectus up to date. Even membership of the European Union is opposed by many nationalists, still less the euro. And the trials of Brexit show how economically damaging the erection of a trade and regulatory border against your main trading partner can be.

So we might end up with a paradox: Scots continuing to vote for the party of independence even though independence has become a vague aspiration, rather than a practical reality. It would be a version of what Scottish literary figures used to call the ‘Caledonian Antisyzygy’.

Comments