Walter Gropius (1883–1969) had the career that the 20th century inflicted on its architects. A master of the previous generation in the German-speaking lands, Otto Wagner, could create his entire oeuvre without venturing outside the city limits of Vienna. Gropius found himself thrust into one unprecedented role after another, uprooted and exiled repeatedly.

His work was carried out wherever he landed — in Germany, England or America. Despite the huge disruptions of history, he displayed extraordinary single-mindedness. From the 1914 Fagus factory onwards, his buildings argued for the modernist position of function over ornament. By the time of his death, in America, the vast majority of practising architects, if not the public, were converted to his position. It is a career of awe-inspiring efficiency.

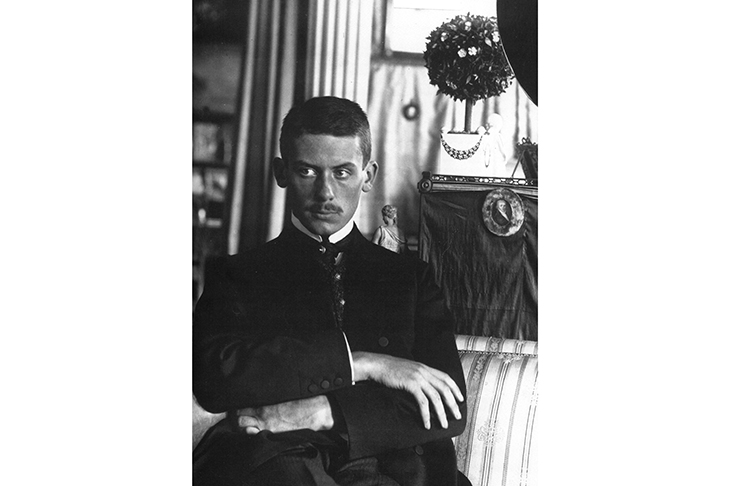

Almost everything that is known about Gropius suggests a person of considerable control and dedication. He came from a professional Berlin family — the Gropius-Bau, the handsome Berlin museum space, was the work of an architect uncle, Martin Gropius. A stretch in military service after 1904 seems to have suited him; strangers would often comment on his upright stance, like a Prussian officer in mufti.

The architectural training was, surprisingly, less thorough, and Gropius left the Konigliche Technische Hochschule in Berlin after two years, without taking a diploma. (He never learnt how to draw properly.) By then he was already designing buildings for family and friends. In 1908 he took a post in the Berlin office of Peter Behrens, a fascinating figure who, according to Fiona MacCarthy, married the monumental simplicity of the classical Prussian architect Schinkel to the aesthetic thought of the English Arts and Crafts movement. The startling result, one of the defining moments of modernism, was the AEG Turbine Hall in Berlin, resembling a vast, unadorned abstract sculpture. By 1914 Gropius himself had made his own major construction, the quite bracingly bleak Fagus factory. This is a man who got his way.

The most important episode in his career, rightly given prominence in MacCarthy’s title, was his founding of the Bauhaus in 1919, unifying two Weimar institutions. In its short 14-year history, the school managed to draw an extraordinary range of aesthetic approaches into a unified project. There was a place in it, at different times, for mystics, poetic fantasists, hard Marxist ideologues, industrial fetishists and dedicated William Morris-type craftsmen. Gropius somehow kept it together, despite its incompatibilities, and in the face of bitter hostility from politicians and the public. After four years it had to move from Weimar to Dessau, where Gropius created the single most persuasive argument for the Bauhaus idea. The school and the idyllic line of masters’ houses in a pine grove must be visited: they embody a compelling vision of a life where work, communal existence, private spaces, creativity and natural beauty can exist harmoniously and concisely.

The Bauhaus lost its equilibrium after Gropius’s departure in 1928, and with Hannes Meyer as director fell under the jurisdiction of the austere Marxist faction. It moved to Berlin in its last year, and was closed down in 1933. Quite helpfully in the long run, Hitler’s persecution sent the Bauhaus masters to all corners of the world. The excellence and persuasiveness of Bauhaus products in Australia, Japan and South America can be attributed to Gropius’s management over those nine years.

He went first to England, where he formed connections with advanced opinion, including the founders of Dartington in Devon and the Isokon project of communal living in Belsize Park, and built a couple of important things. After 1937 he joined the great exodus of German intellectuals to America, where he spent the rest of his life, first as an academic, then as the founder of an architect’s firm. His works from his last years included elegant private residences (the greatest, the Frank House, is kept very private indeed, and his biographer has not succeeded in being admitted to it) and colossal public projects. The largest of these, commissioned as the international style took hold, was for a new university in Baghdad. It wasn’t completed, but by the end of his life Gropius was being imitated and used as inspiration worldwide.

The career, in short, was a triumph of the highest interest, and MacCarthy describes the public side with absorbing power. Her challenge, however, has been to bring out the human qualities of her subject. Gropius has not attracted biographers in the way that his Bauhaus colleague Paul Klee has. His character remains something of a blank, and he comes across as just a supremely efficient public man.

He was married to two unforgettably vivid women. The first, Gustav Mahler’s widow Alma, runs through the history of Jugendstil creativity like an empress in camiknickers. As well as Mahler and Gropius, she married, or had affairs with, Klimt, Kokoschka, Franz Werfel, Zemlinsky and, in a moment of inattention, a mere reptile specialist called Paul Kammerer. Alma was an utterly preposterous figure: her diaries and letters are comically ludicrous. MacCarthy’s biography leaps to life whenever she appears, up until the moment in the 1950s when she published her embarrassing memoirs, largely forgetting that she had ever been married to Gropius. Tom Lehrer’s deathless song about Alma’s life reduces Gropius’s presence to ‘Working late at the Bauhaus’, which about sums up the general impression she gives.

Gropius’s second wife, Ise, was by contrast an intelligent and highly observant woman. On a swelteringly hot day during a trip to Japan after the war she remembered members of a suffering audience ‘pulling their trousers up above their knees’. Her as yet unpublished diaries of the Bauhaus years will one day be a revelation.

But Gropius, despite all MacCarthy’s care, remains an untextured sort of personality. When I wrote a novel about the Bauhaus, The Emperor Waltz, I could do nothing at all with him, and in the end left him out entirely. Most of the expressions of enthusiasm by friends for Gropius in person fall back on his undoubted greatness as an architect. His conduct in his romantic affairs was brisk and time-saving, even when it came to loony Alma. He decided that the sort of secret assignations Alma enjoyed so much were inefficient, and took it upon himself to inform her husband, Gustav, of their affair. Subsequently, he heard Mahler’s Eighth Symphony; considered the question; concluded that, on balance, the value of the work produced, with the support of Alma, outweighed the pleasure of their illicit affair and temporarily ended the relationship.

The chilly rationality of this approach to romance makes you think that Evelyn Waugh got his caricature of Gropius as Professor Silenus in Decline and Fall exactly right. When Paul Pennyfeather asks him whether he doesn’t think Mrs Beste-Chetwynde the most wonderful woman in the world, the professor replies:

If you compare her with other women of her age you will see that the particulars in which she differs from them are infinitesimal compared with the points of similarity. A few millimetres here and a few millimetres there, such variations are inevitable in the human reproductive system.

Waugh also got right the fact that Gropius was clearly very attractive to women, for reasons beyond the excavations of any biographer.

There’s no doubt that MacCarthy’s book is a solid piece of work, and covers the impressive career with admirable accuracy and command. But in the end there is an undeniable sense that — unlike her previous subjects William Morris and Eric Gill — Gropius has escaped her. He is just too methodical: he sought to minimise setbacks and difficulties, he achieved most of what he planned and he did not permit his private thoughts to impinge on his public mission. Great architects, after all, must be efficient managers. Everyone admired him; no one found him boring; he was well-balanced, sensible, decent, professional and open.

If you think biography is most compelling when it excavates the desires and submerged motivations behind a creative mind, however, I can only say that Gropius has not proved fruitful ground to his excellent biographer. The furthest one can go in the way of idiosyncratic character is to say that Gropius usually wore a bow tie, and he once showed enough puckish humour to build a pigsty out of marble. Leave him to the architectural critics, where his magnificent works will always find incisive appreciation.

Comments