Looking at the list breaking down the reasons for which people are granted Personal Independence Payments (PIPSs), up to £180 a week to help them with their daily living and mobility, one cannot help but be reminded of the London Bills of Mortality of the seventeenth century, when some people died ‘frighted’, or of ‘grief’, or ‘lethargy.’

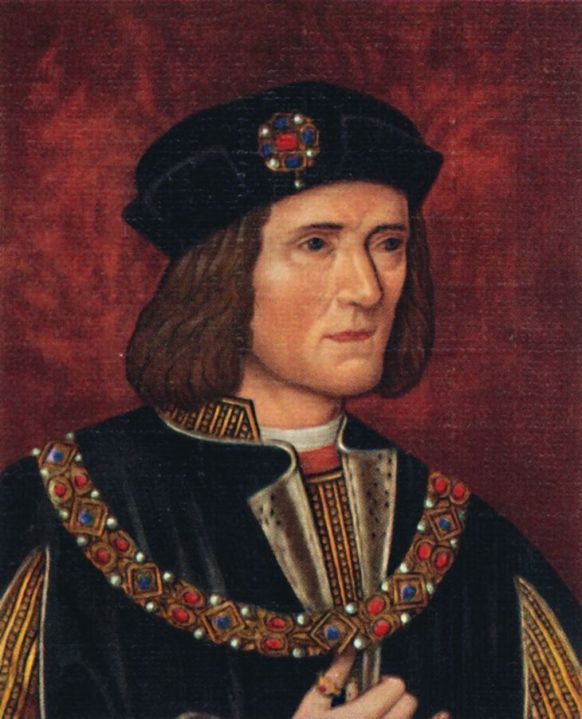

Descanting on his own deformity does nothing to reduce Richard’s unease

Of course, our nosology – our classification of disease – is far more scientific than it was nearly four hundred years ago, except perhaps in one important respect: that of psychological difficulties. This is important because such difficulties are responsible for by far the largest category of claims for PIPs. This, in turn, is alarming because it is often relatively young people who make such claims.

It seems almost as if the volume of PIP grants is inversely related to both the severity and certainty of the diagnosis. Some of the psychological diagnoses are solidly founded, but others, such as anxiety and depression, can be easily simulated. This is not the same as saying that the majority of the hundreds of thousands who claim to be anxious and depressed to the extent of needing financial assistance are faking it: the relationship between what is genuine and what is faked is far more complex than such an assertion would lead one to believe.

To see how and why, it is worth considering Richard III’s opening soliloquy. William Shakespeare was, of course, a very great psychologist, and understood the workings of the human mind as well as anyone who has ever lived.

Richard III’s condition was real (I mean as Shakespeare described it, not as found under the car park in Leicester). He was severely deformed but not handicapped. He did not cry at the Battle of Bosworth Field, ‘My PIP, my PIP, my kingdom for a PIP!’

It takes no great insight, or effort of empathy, to know that Richard’s deformity was no source of happiness to him and complicated his life. No one would rather be born with his deformity than without it; it is necessary only to be a human being, not a psychologist, to know this.

Richard tells that he cannot take advantage of the peace that has broken out:

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks,

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass;

I, that am rudely stamp’d, and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtail’d of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinish’d, sent before my time

Into this breathing world, scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them;

Why, I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity…

This all sounds perfectly plausible and indeed pitiable. As I mentioned, you need not be a psychologist, only a human being, to understand and sympathise with Richard. Nor is Richard necessarily insincere as he speaks in this way.

Yet in the very next scene, he is able to seduce, with less difficulty than a veritable Adonis might have experienced, the widow of a man for whose recent death he has been responsible. It is not true, therefore, that he cannot prove the lover; he is actually very good at making love. Even this, however, does not mean that he is entirely insincere in his lamentation. Common experience demonstrates that, in many cases, no amount of success can assuage the sense of bitterness consequent upon some unfairness or injustice suffered: and Richard’s deformity is nothing if not unfair.

The point is that descanting on his own deformity does nothing to reduce Richard’s unease; on the contrary, it magnifies it, and keeps it constantly before his mind. This is no surprise. Descanting on one’s own anxiety or depression, as the very process of psychological diagnosis encourages the anxious or depressed to do, only magnifies, not assuages, their unease. The movement toward so-called Emotional Intelligence appears to be at the very root of, and a significant cause of, the epidemic of psychological discomfort among the young.

We may go further. Richard says:

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover,

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Having decided, falsely, what he cannot do, he has provided himself with an all-purpose explanation of and excuse for his future behaviour.

I am not, of course, claiming that we have become a nation of Richard IIIs: it is not villains that those who descant on their own anxiety or depression become because they cannot prove the lover, but people who cannot face the difficulties of life (and life is always difficult) without all kinds of props: props that actually maintain their inability that seemingly necessitates them in the first place.

Comments