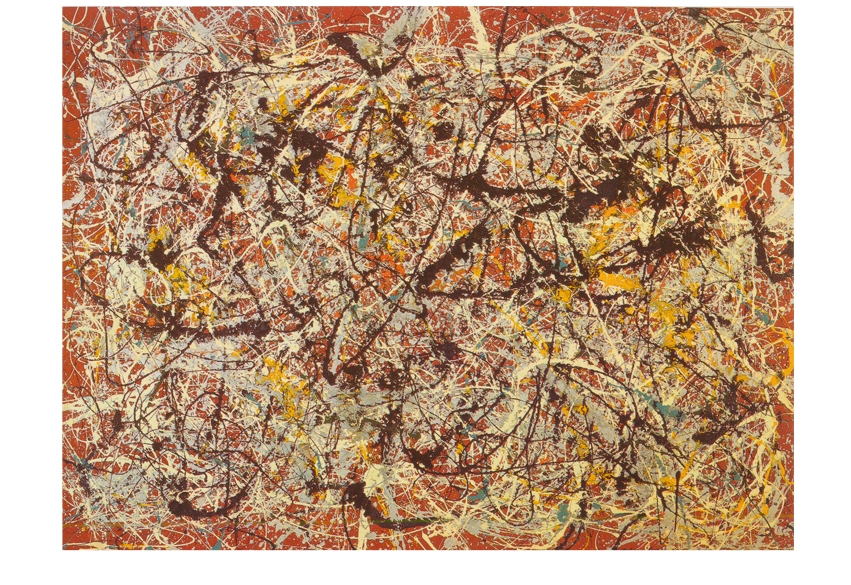

In his centenary year, the status of Jackson Pollock (1912–56) looks assured: a self-created American hero who is now accorded all the reverence due an Old Master. The most famous of the Abstract Expressionists, nicknamed Jack the Dripper because of his trademark style, his emphasis was on paint and process: the surface of the canvas was an arena in which the artist could externalise his feelings through action.

Some have called Pollock the father of Performance Art, but his primary involvement was with pure painting — creating a complex abstract imagery that was intended to engage with Jungian archetypes and thus have access to deep meaning. Of course not everyone was convinced, and for many Abstract Expressionism could not remotely approach the realities of the human condition. As Francis Bacon put it: ‘Jackson Pollock’s paintings might be very pretty but they’re just decoration. They look like old lace…’

After a slow and untalented start, Pollock struck upon a way of working by dripping the paint in long threads and trails on to a large canvas laid flat on the ground, rather than applying it traditionally with a brush. Max Ernst had already experimented with a similar procedure by piercing a hole in a can which was then swung above a canvas on to which the paint was released in a wide or narrow arc. But Pollock was the first to turn a strategy into a technique and exploit it to its full extent. He applied his paint by hand, letting it run off the brush or flicking it in great long spatters, as he moved athletically around the canvas, rhythmically dripping and hurling the paint in a kind of ritualised dance. The term Action Painting was coined to describe this style of work, because of the physical exertion it demanded. After his second solo exhibition in March 1945, the influential critic Clement Greenberg hailed Pollock as ‘the strongest painter of his generation’.

Pollock’s moment of glory was short-lived. For five years he was able to ride the whirlwind of his success, during which time he not only wrestled with the paint but also with his demons. He had been declared emotionally unstable (with ‘a certain schizoid disposition underlying the instability’) by his psychiatrist when it came to fighting in the war, and he resorted to alcohol to contain or calm his fractured nature. Drink achieved neither, and made him inarticulate and aggressive. Of course, deprived of his inner conflict it’s entirely likely that Pollock would have had nothing to paint about, and therefore nothing to justify the great struggle with paint. If a psychiatrist had been able to ‘cure’ him, we would not have had the paintings. Instead the result was a series of extraordinary and very beautiful works of art, unlike anything before or since, and an increasingly off-the-wall artist.

As John Updike has observed, America loves an emblematic life, and Jackson Pollock’s life-narrative of ‘long struggle, high triumph and swift fall’ fits the bill rather neatly. The Abstract Expressionists are still viewed by many as working on a heroic scale and making heroic stylistic breakthroughs, of which Pollock’s ‘epic’ drips are perhaps the most engaging. His paintings certainly encourage an elemental subjective response in the viewer: abstract pools and lines suggest space and its limits, openness and closure, symbolic themes of the utmost gravity. Line is disassociated from its traditional role of describing the outside of things, from holding a composition together, and deployed instead to blow it apart. But actually line still does hold Pollock’s paintings together, in a rhythm which is also a pattern, like a snaking net, or a braided thread.

Pollock was the first American artist to become really famous, which can be seen as a triumph of need over skill. His early work was muddy and undistinguished, and he was more in love with the idea of being an artist than with actually making art. He studied briefly under the Social Realist painter Thomas Hart Benton and liked the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder and the Mexican muralists. Later, he was impressed by Picasso, primitive art, Miró and the other European surrealists. Kandinsky was an important influence, and Pollock’s mature art might with some justification be called Abstract Surrealism, even though the depths of exhilaration and despair provoked by excessive self-reflection eventually required a decidedly Expressionist outlet.

At the time it was made, Pollock’s art was considered wild and violent, threateningly transgressive. Today it looks elegant, even serene, and beautifully modulated, the colours and tones exquisitely controlled. The energy remains but it is corralled, lassoed by Pollock’s whirling lines. The myth states that the struggle took place spontaneously, that Pollock fought and wooed the paint in one great session of lovemaking, and a major painting resulted.

The reality wasn’t quite like that, and he would often retouch the drips later with a brush to improve them. Pollock was not a natural draughtsman, but his lines achieved new grace when he threw his paint through the air — as if metamorphosed by the different element. His method transcended his own inabilities and turned him into a great artist.

This transmuting of base metal into gold is such a rare event that it makes him a dangerous role model for young artists. The fact that it worked for Pollock is no guarantee that the magic will ever work again. His was an intensely personal solution, and it’s the intensity of the art that lingers and convinces, not the myth. He created a form of all-over painting that challenged all norms and preconceptions and shook up how people thought about art. As de Kooning admitted, it was Pollock who ‘broke the ice’ for American painters.

In Arnold Newman’s moody photo-portrait of Pollock (above), taken in 1949 for the Life magazine profile that proclaimed him the greatest living painter in America, the artist, his face corrugated with pain, stands against the gappy wooden wall of his painting hut. Next to him on a shelf reposes a human skull, while in front of him is a table cluttered with paint pots from which protrude a thicket of brushes and sticks. The skull and the brushes seem to hem him in, to pin him against the wall. Pollock looks more like a miserable garage hand or mechanic than an artist. But this was part of the macho, non-arty image he espoused, a lifestyle that in his case led to alcoholism, long bouts of inactivity and destructive self-doubt.

Between 1948 and 1950, when his reputation was really taking off and the photographers were coming to call, Pollock was mostly sober. He started drinking again as soon as the famous 1950 filming session with Hans Namuth was over, perhaps disturbed by the thought that the whole thing had been set up for camera, and was thus phoney. He hated and feared phoniness and the best of his art has exceptional freshness and authenticity. Namuth’s film, of the quintessential Action Painter in action, is remarkable, but it probably triggered Pollock’s rapid downward spiral. He had betrayed his muse by faking his procedures and he had to suffer the consequences. Or, looked at another way, how could he keep on venturing into the unknown, deep within the self, without the process exacting a terrible cost?

Pollock’s art got stuck around 1950 and in his depression he took more and more to drink. His death in a driving accident at the age of 44 was probably the only solution he could see.

Comments