When Theresa May appointed me as a non-executive director of the Office for Students, the Downing Street press office decided to embargo the news until midnight on New Year’s Day 2018. It may be that it hoped to slip it out under the radar, calculating that most journalists would be too drunk to notice. If so, it didn’t work. The Guardian decided it wasn’t going to let the government get away with this sleight of hand and stuck the following headline on its website at 12.01: ‘Toby Young to help lead government’s new universities regulator.’ The offence archaeologists immediately set to work digging through everything I’d said or written, looking for material to be outraged by. It didn’t take them long to find it. By 12.05, I was trending on Twitter.

Perhaps it would have been more sensible to promote the story in the usual way – press release, interview on Good Morning Britain, etc. It probably would have been ignored. That seems to have been the response to the announcement this week that I’ve been asked by the leader of the opposition to head up a policy commission on free speech. Both Kemi Badenoch and I wrote articles about it, CCHQ issued a press release and I’ve been doing my best to promote it on social media. But, so far, it’s caused barely a ripple.

I daresay that’s for the best. When Kemi first asked me to do it, I worried it might result in another pile-on. Would the diggers get going again? Admittedly, the last Conservative leader to give me a job was prime minister at the time, which made me a bigger target. It was also a public appointment, which meant certain rules of propriety had to be observed. Seven years ago, one dogged Torquemada found an article I’d written for The Spectator in 2001 headlined: ‘Confessions of a porn addict.’ He stuck a screenshot on Twitter and, two hours later, the Evening Standard ran the following story: ‘New pressure on Theresa May to sack “porn addict” Toby Young from watchdog role.’ That gave a nice boost to the petition calling on her to sack me, which topped out at 220,000 signatures.

Another reason I thought I’d be safer this time is because the body I’m heading up is looking at ways to tackle Britain’s free speech crisis. Labour’s standard response to such concerns is to dismiss them, claiming freedom of expression has never been in better health. Any suggestion it’s on life support is just a culture war trope put about by right-wing grifters. (See Keir Starmer’s reply to J.D. Vance when he raised the issue.) It would be difficult to maintain that line while dredging up stuff I said on social media ten years ago in an effort to defenestrate me.

Then there’s the ‘double jeopardy’ rule when it comes to cancel culture. It’s not a hard-and-fast law that you can’t be cancelled for the same thing twice, but the ‘porn addict’ stuff would definitely have less impact second time around. I’ve served my time in the stocks, having stepped down from five positions in 2018, so it would feel a bit unfair to be punished all over again for the same sins. A similar rule applies to political scandals, which is why Angela Rayner is already talking about a comeback and we may not have seen the back of Peter Mandelson. He recovered from two scandals after a spell in the wilderness. Why not a third?

Finally, there’s the fact that no serious attempt was made to re-cancel me when I was nominated for a peerage in December. I was terrified that there would be, and Caroline thought it unwise to let my name go forward for that very reason. But the only person to reproduce all the worst things I’ve ever said – my very own greatest hits album – was Alan Rusbridger, the ex-editor of the Guardian. Cheers, Alan.

The ‘porn addict’ stuff would definitely have less impact now. I’ve served my time in the stocks

I hope that having been cancelled will inform my work as the head of this policy commission. I’m thinking about recommending an amendment to the Employment Rights Act, which would create a one-year statute of limitations on what social media posts you can be sacked for. That would stymie the snowflakes. It would also mean more people might be willing to enter public life, confident they won’t be put through the wringer for telling a dirty joke in a private group chat eight years previously (as one of Starmer’s aides was this week).

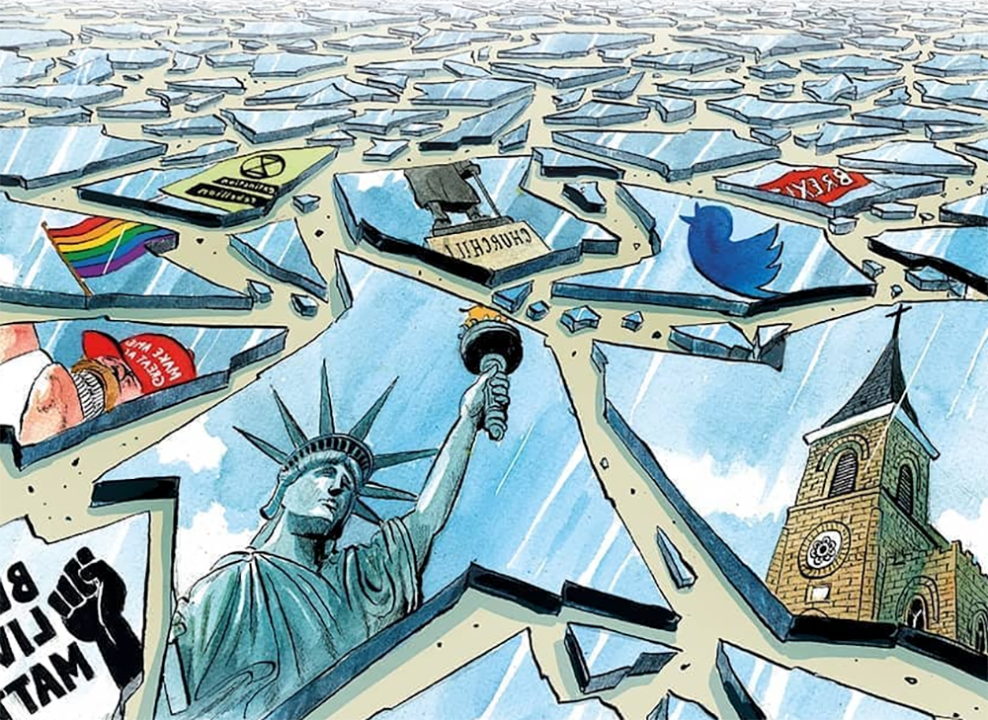

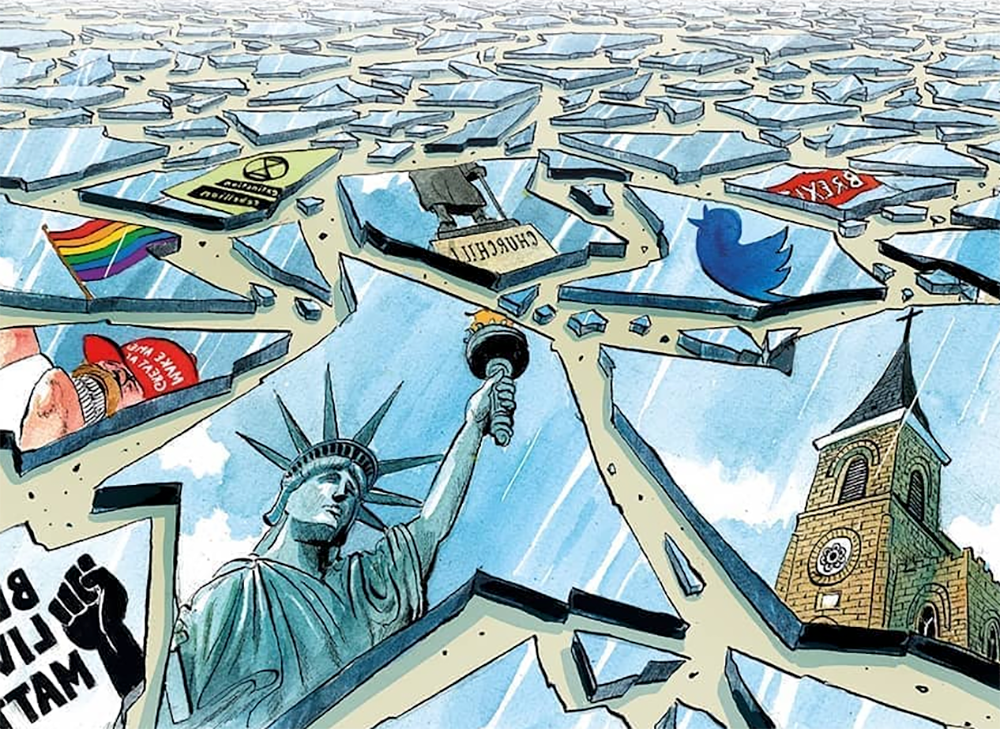

Social media has created a kind of shooting gallery in which anyone who puts their head above the parapet is fair game. That’s the nub of the free speech crisis – people being afraid to say anything remotely colourful or contentious for fear it will be screenshotted and used against them.

Comments