As Hilary Mantel memorably noted, history represents what people try to hide, and researching it is a question of ferreting out what they want you not to discover. Claire Hubbard-Hall’s plan to unearth the identities and lives of the legions of women who have worked unheralded in the British secret services was bold: looking for secrets in a doubly secret world.

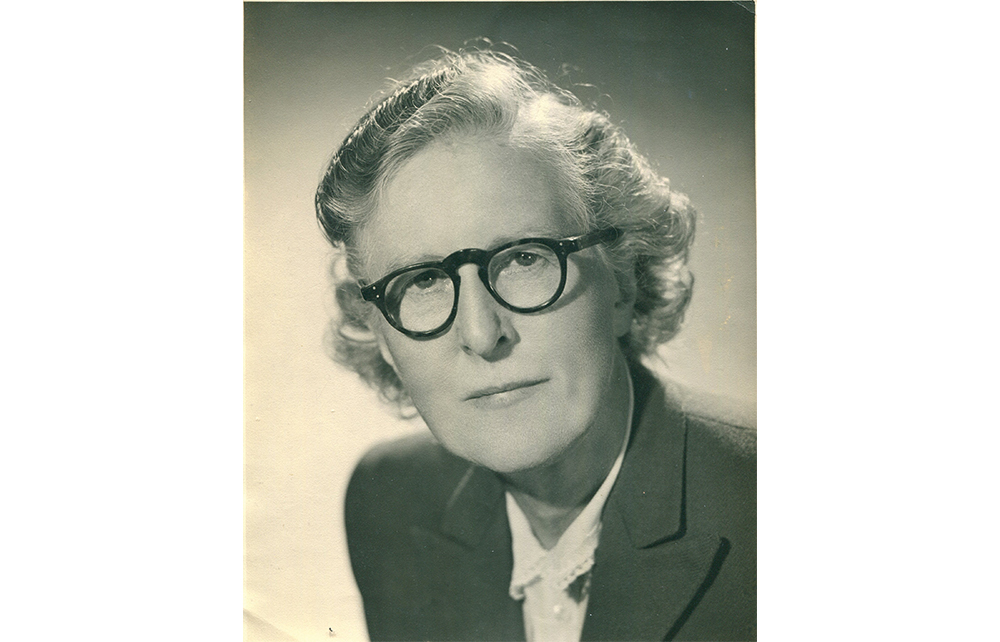

Miss Pettigrew was a ‘formidable grey-haired lady with a square jaw of the battleship type’

The first bureau was founded in 1909. It is perhaps not altogether surprising to learn that neither MI5 nor MI6 were very good to the female employees on whom they came increasingly to depend. Perceived as secretaries but given tasks unrecognisable in the normal secretarial world, young women were recruited in the first world war to organise and manage incoming secret messages, navigate a vast world of paperwork and in due course extract information from encrypted signals and captured documents.

Having signed the Official Secrets Act – official secrecy was defined in law only in 1911 – women were deemed by those in charge to be persevering and intuitive. They were credited with good memories and many seemed happy to work night and day. Unlike their male colleagues, they seldom left the office. Secret service work was ‘capital sport’, and agents – all men – hired their disguises from theatrical agencies.

Hubbard-Hall opens her book at a time when intelligence still involved pen and paper; she ends it in the era of sophisticated technology. Determined to find and describe as many individual women as she could, her book contains a vast cast of characters, many of whom flit only briefly across the page; but over the years, she suggests, they succeeded in shaping a matriarchal hierarchy in the world of intelligence.

A few of the women stand out. Kathleen Pettigrew – one of the models for Ian Fleming’s Miss Moneypenny – joined the Special Branch of the London Metropolitan Police in 1916, aged 18. Unusually (since many recruits came from a wealthier world), she was the daughter of a sealskin worker in South Bermondsey. Her three aunts had been models for the painter John Millais. Like them, she was confident and supremely efficient. By the time of the second world war, she was deeply embedded in MI6 as personal secretary to its chief, and all secret intelligence passed through her. A male colleague’s description says much, not just about her but about the way in which such women were viewed. Miss Pettigrew was a ‘formidable grey-haired lady with a square jaw of the battleship type’. You did not mess with her.

The more attractive Winifred Spink was born into a family of Plymouth Brethren. A rebel and a suffragette, she studied French and German and became a competent car mechanic. Her secretarial skills were excellent. Shortly before the 1916 revolution, she was sent as the first female intelligence officer with the British mission to Petrograd, where she narrowly escaped being shot. As liberated as she was brave, she recorded her many sexual encounters in her diary as ‘another scalp’.

Then there was Olga Gray, who began working for MI5 in 1931, infiltrated the British Communist party as secretary to its leader Harry Pollitt, and managed to unmask a Soviet spy ring. Joan Bright, another model for Miss Moneypenny, described as the ‘organising genius of the War Office secretariat’, became the gatekeeper to its secrets in the second world war and a source of information for historians for the rest of her life.

Spink’s engaging panache was unusual. Many of the women who joined the secret services in the two world wars led considerably greyer lives. They worked ferociously hard, and while it was accepted that they were doing the same job as the men they received neither the same official rank nor pay, and were forced to watch from the sidelines while their male colleagues had more fun. They were discreet and loyal and often remained single. MI5 and MI6 became their families. As one male officer put it, these women possessed a great capacity for ‘cool and lonely courage’. As a catalogue of failed recognition and blocked promotions, Her Secret Service makes sorry reading.

The end of the second world war brought little change. When a woman was suggested for an officer post in Jordan in 1946 a senior agent commented doubtfully that it might just work, provided she was ‘of a certain age’ with a ‘forbidding appearance’. It was not until the 1970s and the end of the Cold War that British women began to reach the top echelons of the secret services.

It is as a portrait of the female administration of the two wars, the sifting, decyphering, compiling and storing of crucial information, that Hubbard-Hall’s book stays in the mind. For all its tributes, this compendium of doughty forgotten women, diligent housekeepers of office war work, is a little sad.

Comments