The Great Gatsby is one of those great works of literature, like Pride and Prejudice, that appeals as much to the general reader as to the literary bod. It’ll always be around, if not as a movie (there have been five since its publication in 1926) then as an opera or a ballet. Last year a staged reading ran for weeks in the West End, to critical acclaim.

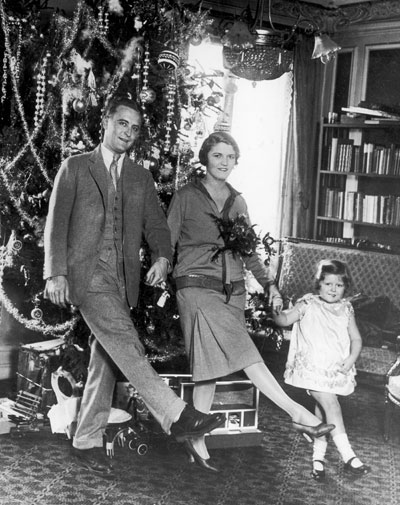

It is a short book — a long short story really — about wealth and sex and hope and disillusion and partying. These are the themes, too, of the lives of its author and his wife Zelda. Theirs was a relationship that continues to fascinate as powerfully as any fiction, and so has produced fictions to investigate it. After all, as Fitzgerald told his biographer Malcolm Cowley: ‘Sometimes I don’t know whether Zelda and I are real or whether we are characters in one of my novels.’

There have always been Fitz novels (the first was Bud Schulberg’s The Disenchanted in 1950) and there are more to come this year. So what is the attraction? Well, there is something (for the novelist) providentially structured in the Fitzgeralds’ story, an inviting series of dualities and polarities. It takes place over two greatly contrasting decades, bookended by Scott’s own This Side of Paradise (1920) and Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939). What begins with Flappers, yellow automobiles, champagne and jazz ends in bums, freight cars, ruin and war.

The fate and fortune of the Fitzgeralds mirror this division, as they mirror each other, he dissolving into alcoholism, she into psychiatric chaos. Then there is the small-town America they both came from as against New York and Paris. And in Scott Fitzgerald himself there is the desire for fame and wealth and a self-disgust that accompanies that desire.

And they plainly really were in love.Therese Anne Fowler’s Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald is a biography disguised as fictional autobiography. The point of books like this is hard to discern. If your skills as a novelist do not extend much beyond the ‘and then and then’, plus heavily plonked bits of exposition, why not simply write a straight biography? Possibly because Zelda’s life has already been done well enough by Nancy Milford.

Some of Fowler’s dialogue is downright embarrassing, a cocktail of ersatz romance and what might be termed fem lite: ‘Does he love you — and I mean genuinely, for the special person you are and not just some idealised feminine object?’ It is impossible to imagine Zelda Fitzgerald having patience with such a dull if earnest friend.

Fiction allows (indeed encourages) the lie, so in Fowler’s book Zelda can emerge as an heroic, brilliant woman done down by a repressive patriarchy represented by her husband. It is more likely that Zelda Sayre, however beautiful, spirited or independent-minded she was, would have been unknown to the wider world had she not married a great novelist.

R. Clifton Spargo’s Beautiful Fools, subtitled ‘The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald’, is the work of a genuine literary talent. The author’s interest in his subject is more intimate, more a forensic exploration of the nature of dysfunctional love.

His well-evoked mise-en-scène is the steamy Cuba of April 1939, where Scott and Zelda spent their last days together. Scott had become a boring alcoholic and Zelda had spent much of the previous decade in lunatic asylums. Spargo’s characters transcend reality and become rich and fictional, and the novel, in the form’s paradoxical brilliance (at its best, as often here) speaks truth through invention. Spargo’s Fitzgeralds come alive.

Much of Sarah Churchwell’s book, Careless People, has been done before, by Ronald Berman, but not quite so enjoyably. Churchwell is the engagingly enthusiastic American academic who appears on the BBC’s Review programme. She is not right about everything (and quite wrong about Tom Wolfe’s latest masterpiece) but she does make you listen, and her writing has a similar jauntiness.

This is quite a feat, given the complex structure she has imposed on her book. Careless People weaves together three narratives, mixing ‘explication with intimation’ in its reading of The Great Gatsby. Written in nine chapters, each addressing themes arising in the nine chapters of the novel, Churchwell at the same time probes a real-life murder she believes inspired Fitzgerald’s plot. In and around this she has written a social history of New York in the four months at the end of 1922, the year in which Gatsby is set, the year of the murder, and the year in which Scott and Zelda lived in Great Neck, the setting of the novel. It sounds overwrought, but actually the result properly illuminates the now distant world of Fitzgerald’s little masterpiece.

Occasionally she is carried away by the born researcher’s desire to note every conceivable coincidence she comes upon. In her own defence, she quotes Fitzgerald telling his editor, ‘I insist on reading meanings into things’, and admits that her own book takes this ‘as an article of faith’.

There is, for example, the green light. Jay Gatsby has bought a house facing across Long Island Sound, opposite the home of Daisy Buchanan, the woman in whom all his hopes and dreams are gathered. The first time the reader sees him he is staring at a green light marking Daisy’s jetty. He is trembling. Much has been made of the green light. What does it symbolise? Hope? Jealousy? Yes? No?

Sarah Churchwell doesn’t explicitly say so but she spends a good deal of time suggesting that the new traffic-light system installed in Manhattan during the course of 1922 may have inspired this ambiguity of meaning. Green apparently sometimes meant ‘stop’ and sometimes ‘go’. There is an extraordinary picture of one of these traffic lights. It resembles a guillotine. A stretched point, but intriguing.

Neither of the novels reviewed here will increase the reader’s enjoyment of Fitzgerald’s books. Sarah Churchwell’s will. And before (or after) you see the movie, re-read The Great Gatsby.

Comments