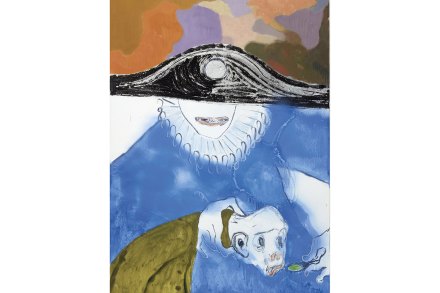

Figurative painting is back – but how good is any of it?

An oxymoron is a clever gambit in an exhibition title. The Whitechapel Gallery’s Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium is designed to trigger the reaction: ‘Radical? Figures?’ before revealing quite how radical the figure can be. But like all good marketing, it is deceptive. Figurative art may have been consigned to history by Clement Greenberg 80 years ago, but history since — neo-romanticism, school of London, neo-expressionism — has repeatedly proved him wrong. The ten painters in this exhibition aren’t a school: the only thing their work has in common is its statement-making scale. The three-metre canvas at the entrance, Daniel Richter’s ‘Tafari’ (2001), was inspired by a news