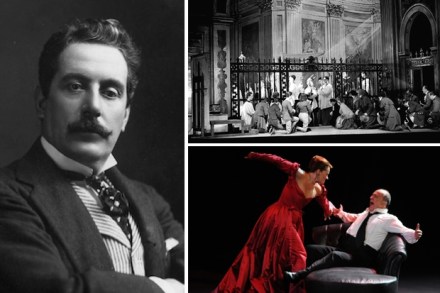

In defence of Puccini

During my opera-going lifetime the most sensational change in the repertoire has, of course, been the immense expansion of the baroque repertoire, with Monteverdi, Rameau and above all Handel being not only revived but also seen now as mainstays in most opera houses. To think that only 50 years ago it was regarded as daring for Glyndebourne to mount L’incoronazione di Poppea, even in Raymond Leppard’s abbreviated and sumptuous version, which has been most unfairly denigrated in recent years. Yet just as remarkable, though hardly ever remarked on, has been the instatement of Puccini (who never needed reviving, since after initial scandals and flops he has always been more or