Why David Bowie is still underrated

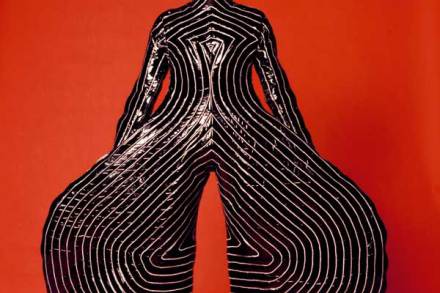

Is it just me, or is there quite a lot being written about David Bowie at the moment? Of course, there’s the fact that the V&A’s blockbuster exhibition has coincided with the totally unexpected appearance of his first album for ten years. (While putting the exhibition together, the curators could never have dreamed that on the day it opened, a new Bowie album would be number one in 40 countries.) Yet for some cynics on the internet — never hard to find — the recent outbreak of Bowie mania is a simple question of demographics: the media is now run by people who grew up with him, and apparently never