‘I couldn’t afford loo roll’: Bruce Robinson on being skint, Zeffirelli’s advances and Withnail’s return

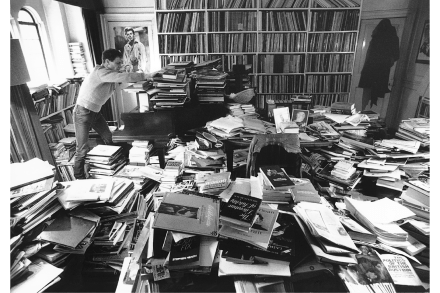

Bruce Robinson is ramming a huge log into the grate of his ancient fireplace in mud-clogged Herefordshire. He’s 77 and the film for which he is famous, Withnail and I, is about to open as a play. Isn’t it curious it hasn’t happened before, given that the comedy is about two thirsty, unemployed actors and is a sort of love-hate letter to the theatre? ‘I was living on 30 bob a week – I could either afford fish and chips or ten gold leaf’ ‘I wasn’t fond of the idea of staging it,’ says Robinson, who wrote and directed the 1987 film based on his own boozy life as an