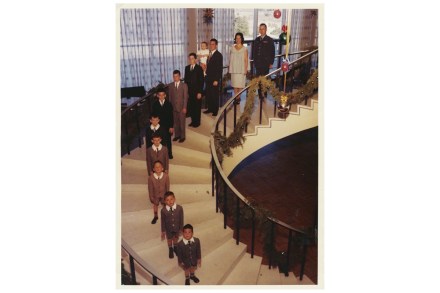

When six of her 12 children went mad, Mimi Galvin did her best to make to light of it

Don Galvin and Mimi Blayney married in December 1944. It was a shotgun wedding. They had been high school sweethearts. Just before Don was about to be shipped out to join the fighting in the South Pacific, Mimi called from New York to say she was pregnant. A rushed wedding across the Mexican border in Tijuana followed: a not uncommon wartime story. But Mimi’s pregnancy turned out to be the first of a dozen, each accompanied by severe morning sickness. Between 1945 and 1965, a procession of children arrived, ten boys and then, at last, even after Mimi’s gynaecologist had warned that further pregnancies might prove life-threatening, came two girls.