Christopher Caldwell, Gus Carter, Ruaridh Nicoll, Tanya Gold, and Books of the Year I

34 min listen

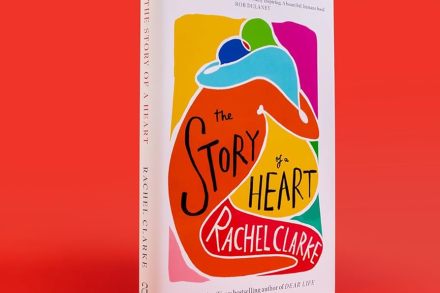

On this week’s Spectator Out Loud: Christopher Caldwell asks what a Trump victory could mean for Ukraine (1:07); Gus Carter argues that leaving the ECHR won’t fix Britain’s immigration system (8:29); Ruaridh Nicoll reads his letter from Havana (18:04); Tanya Gold provides her notes on toffee apples (23:51); and a selection of our books of the year from Jonathan Sumption, Hadley Freeman, Mark Mason, Christopher Howse, Sam Leith and Frances Wilson (27:08). Produced and presented by Patrick Gibbons.