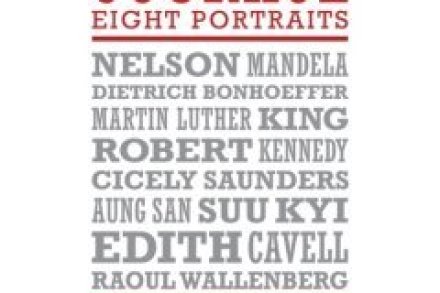

The charnel house of liberty

Ever since I began to serve sentences of imprisonment three decades ago I have preferred not to know too much about what I’m missing outside. Whenever I do find myself receiving a social visit, crammed in amongst squabbling (or more often dysfunctionally silent) families enjoying their monthly 40 minutes together, I tend to steer the conversation deliberately away from the natural subjects of free men — which was how I came to learn about a somewhat unlikely ‘imam’ ministering to the needs of Muslim prisoners in Guantanamo, one Colonel Steve Feehan, ‘born again’ Southern Baptist, who had had this greatness thrust upon him after the previous incumbent, official Muslim chaplain