The feel-good football story of Watford Forever

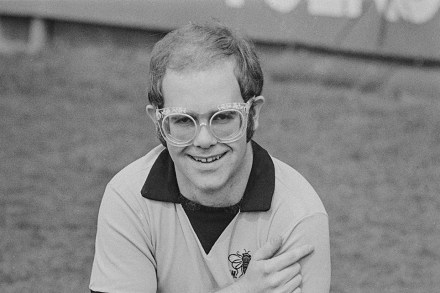

One Saturday in 1953, the six-year-old Reggie Dwight of 55 Pinner Hill Road went to his first football match with his perennially gloomy father, Stanley. ‘Emerging from the Tube station,’ writes John Preston, ‘Stanley reached down and took his son’s hand.’ Reggie was enchanted by Stanley’s sudden happiness. The only place the two would ever manage to connect was on the stands at their beloved Watford FC. Once Reggie became the rock star Elton John, he bought the club and took it, improbably, to the top. He did it with a manager who was both his opposite and his soulmate, Graham Taylor – better known for his later disastrous reign