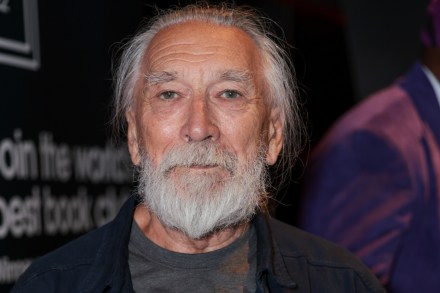

M. John Harrison’s ‘anti-memoir’ is a masterpiece

It would be hard to categorise M. John Harrison as a novelist, and that is just the way he would like it. He may definitely have a foot in the camps of science fiction and fantasy – with fans including Neil Gaiman and the late Iain Banks – but he is not one for being pinned down, whether he steps outside those genres or not. Of his 1989 novel Climbers, he said: It isn’t about somebody who ‘finds himself’ through climbing, or who ‘becomes a climber’. It’s precisely the opposite of that: it’s about someone who in failing to become a climber also fails to find a self. And so