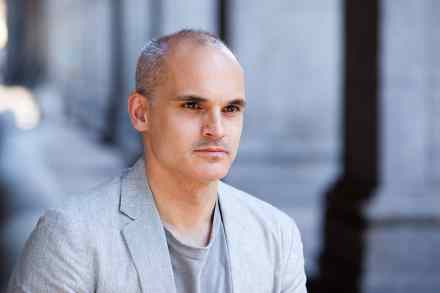

From the archives: Francis Fukuyama

37 min listen

This week we spotlight our most popular episode of the last year, Sam’s conversation with Francis Fukuyama about his book Liberalism and its Discontents. He tells Sam how a system that has built peace and prosperity since the Enlightenment has come under attack from the neoliberal right and the identitarian left; and how Vladimir Putin may end up being the unwitting founding father of a new Ukraine.