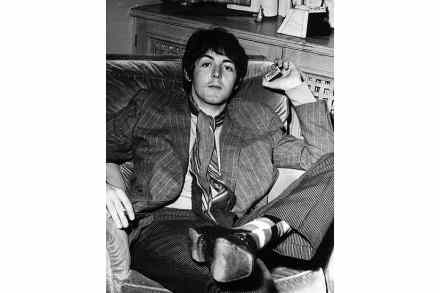

The nearest thing to Paul McCartney’s autobiography: his guide to the Beatles’ songbook

Whatever your favourite theory of creativity, Paul McCartney has a cheery thumbs-up to offer. You think the secret is putting in the hours? ‘We played nearly 300 times in Hamburg between 1960 and 1962.’ Or could it be a wide range of cultural inputs to assimilate and remix? The Arty Beatle hoovered up Shakespeare, Dryden, not just Desmond but Thomas Dekker, Berio and Cage and rock’n’roll and light jazz, and sublimated them all. In one of the great missed opportunities, when it came to arranging ‘Yesterday’, his first thought was Delia Derbyshire. Some people credit childhood trauma: McCartney recalls how his father Jim would weep alone in a neighbouring room