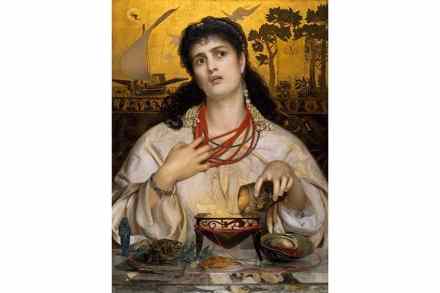

A modern Medea: Iron Curtain, by Vesna Goldsworthy, reviewed

Vesna Goldsworthy’s finely wrought third novel explodes into life early on with a shocking scene in which Misha — the boyfriend of our protagonist, Milena Urbanska — returns from a short, tough spell of military service, initiates a game of Russian roulette (‘the only Russian thing I could face right now’) and blows his brains out. It is 1981. Misha and Milena are children of the political elite in an unnamed capital city in the Eastern Bloc. As such, they are afforded privileges their compatriots lack: palatial homes, preferential treatment, western luxuries as seemingly innocuous as cans of Bitter Lemon from Italy and imported tampons, instead of ‘the scratchy home-produced