Dramatically riveting and visually superb: Dear Octopus, at the Lyttelton Theatre, reviewed

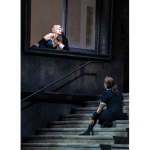

Big budget, huge stage, massive temptation. The Lyttelton is a notorious elephant-trap for designers who feel obliged to fill every inch of space with effortful proof of their brilliance. Frankie Bradshaw, designer of Dear Octopus, avoids these snares and instead creates a modest playing area, smaller than the actual stage, which is bookended by a doorway on one side and a fireplace on the other. These physical boundaries draw the actors towards the middle of the stage with a staircase overhead to complete the frame. Brilliant stuff. Perfectly simple, too. Any director planning to work at the Lyttelton should see Emily Burns’s fabulous production. So should everyone else. This is