How we fell for antidepressants

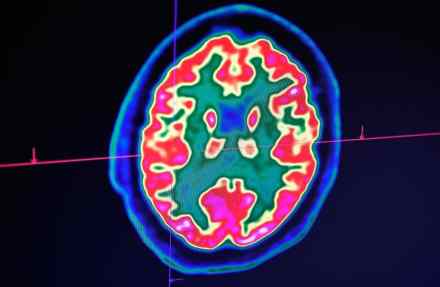

The French novelist, Michel Houellebecq, with his accustomed acuity about modern culture, titled his last novel but one Serotonin. By then, of course, this famous neurochemical had become the key to a perfect human existence, too little or too much of it resulting in all the little problems that continue to plague mankind. If only we could get the chemical balance in our brains right, all would be well, life would return to its normal bliss! After the commercialisation of Prozac, people started talking about the chemical balance in their brains in much the same way as they talked about the ingredients of a recipe. As Peter D. Kramer put