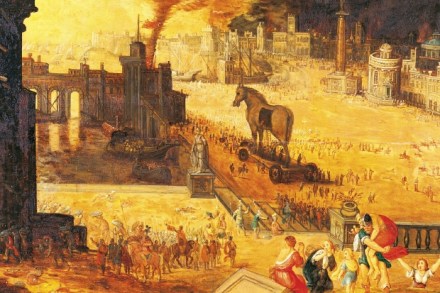

Trapped in hell

The mechanic, blinded in one eye by shrapnel, spent three days searching for his family in the destroyed buildings and broken streets of Darayya. Finally he found his father’s body in a farmhouse, alongside those of three boys, already starting to decay. ‘Can you tell me why they would kill an old man?’ he asked,